Several years ago I wrote about the pervasive orphanage industry in Cambodia, particularly in relation to orphanage tourism. The Cambodian government has been well aware of the need for reform of orphanages for many years, and has been working with UNICEF and child rights NGOs to try to shut down dodgy operators and reintegrate children back into their families and communities – but it has been slow going (also see here).

It has also been surprisingly controversial. Some argue that it is ‘not all orphanages’ that cause a problem, and only the bad ones should be targeted. Others (i.e., UNICEF – see PDF) argue that institutionalising children is damaging no matter how well cared for they are and should only be a very last, and very temporary, resort.

Australians have a lot to answer for when it comes to Cambodia’s ‘orphanage problem’, being among the most involved in visiting them as tourists, starting them up and financially supporting them. They’ve also been behind some that have been shut down in recent years. So it is no surprise that knee-deep in this debate around the future of residential care in Cambodia are two high-profile Australians who have started orphanages, but who are now changing tack – one more willingly than the other.

On one side is Sunrise Cambodia, led by outspoken Australian Geraldine Cox. The organisation, which was formerly called Sunrise Children’s Villages, and was definitely an orphanage NGO (see previous advertising here), has now rebranded itself as ‘not an orphanage’, right across the top of its website.

Sunrise has a high and positive profile in Australia, where it secures most of its support, and its orphanages have always been considered to be among the well-run, despite allowing visitors, and in the past, accepting voluntourists. But within the development worker community in Cambodia, views about the organisation and its controversial founder are mixed. For starters, there is Cox’s close associations with the Hun Sen regime (detailed here), and her constant claims that she is the ‘big mum’ to all the children in Sunrise’s care and that they are ‘her children’.

Secondly and more recently, there has been backlash against the organisation’s fundraising communications, with critiques of it being poverty porn and exploitative of children. The response of Sunrise’s new CEO Lucy Perry, formerly of Hamlin Fistula Ethiopia, didn’t help calm things down – Australia’s peak NGO body was even drawn to comment.

Thirdly, there has been criticism of the organisation’s slow response to Cambodian government efforts to deinstitutionalise children who are actually not orphans, and to have them return to their communities and families.

Sunrise has refuted this criticism (they have blogged about it, and the comms controversy, here). But while the organisation is saying one thing, its outspoken leader is still resistant – see a Fairfax article and video, and a Triple J Hack story, both from just a few weeks ago, where Cox argued that orphanages are the only answer for some children who don’t have families to return to, and made it quite clear that she was reticent about reintegrating all ‘her children’ into their families. In the stories, she argues that when children go home for visits they are not fed enough and that some with disabilities simply can’t be reintegrated. As the Fairfax article sums up, she says ‘nobody is going to take all her children away from her’.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the debate, another Australian who has also attracted widespread attention for her work ‘saving’ children from a corrupt orphanage at the age of 21 has written a book about her experience, dispelling the martyr myth around her story, slamming the harmful practice of residential care, and trying to dissuade others from making similar mistakes.

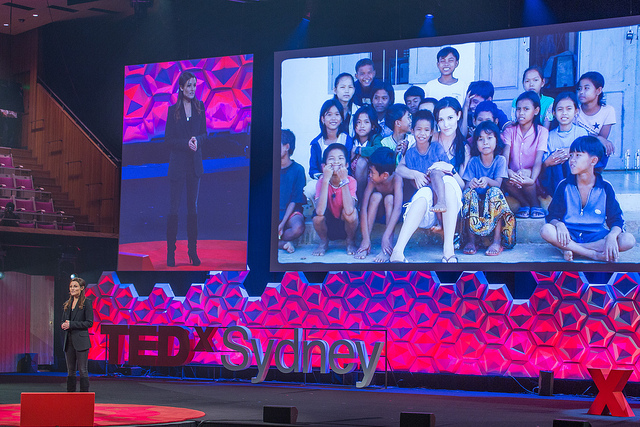

Written for a very general audience and by no means for development wonks, Tara Winkler’s How (not) to start an orphanage – by someone who did takes the reader through her experiences of getting in over her head after fundraising for and volunteering at a corrupt Battambang orphanage. After realising what was going on, she created her own orphanage with the help of concerned locals to transfer the kids to safer circumstances, but now cautions others against doing the same. Her overarching message is: don’t start or support orphanages if you really want to help.

Though a memoir by someone who still works in the biz and who is still raising funds for her organisation’s work (Cambodian Children’s Trust, or CCT), so one that needs to be taken with a grain of salt, Winkler details some hard lessons and many set-up and growing pains that will be familiar to anyone who has been involved with smaller NGOs. After realising the problematic nature of the orphanage model, and taking quite a while to realise that many of the children in her organisation’s care weren’t actually orphans and were suffering attachment and behavioural issues as a result of being away from their families, she has moved CCT towards being focused on family-based care – keeping children with their own families whenever possible, but otherwise placing them with local foster families.

Deinstitutionalising kids has been a tough process for CCT, so Winkler most strongly advocates for not institutionalising them in the first place and her organisation now runs a campaign against residential care institutions.

While there are some eye-roll worthy moments in Winkler’s book, it’s hard not to have a degree of sympathy and respect for her. After all, who hasn’t been 21, outraged by injustice, naïve and somewhat impulsive? Her willingness to be upfront about the mistakes made, her moral dilemmas about how to do the right thing by the children in her organisation’s care, her work with her Cambodian team to make a major change to their approach, and her effort to put it all down in a book that is accessible for anyone who might be tempted to engage in activities that support the orphanage industry, are all admirable.

Winkler and Cox’s stories share many similarities – Australian women who have managed to mobilise a significant amount of resources (no small feat) to support the running of orphanages in Cambodia, who have both been significantly recognised because of it (Winkler was Young Australian of the Year for NSW in 2011, Cox has an AM and a Centenary Medal and they’ve both been featured on shows such as Australian Story multiple times), and also criticised for it.

But now, given their split views on the future of residential care in Cambodia, that seems to be where the similarities end, and the once-close pair have fallen out.

There’s no doubt that learning and engaging with changing thinking about the ‘right way’ to do development and to develop best practice is important for any organisation – and it throws up big challenges, particularly when trying to maintain a fundraising base while shifting gear. But times are changing, albeit slowly. Hopefully the Australian public will start to get the message that there are better ways to ‘save’ the children of Cambodia than to support orphanages.

Ashlee Betteridge is a Research Officer at the Development Policy Centre.

Check out what Dr. Richard Mckenzie had to say in my podcast show about the role of orphanages.

Episode #19: One man’s response to J.K. Rowling’s tweet: “Orphanages cause irreparable damage, even those that are well run.”

Great article. I spent a few months in Cambodia last year and met some Christians from the US who had come to Cambodia to set up orphanages where the children were “encouraged” to become Christian.

I remember feeling so furstrated and angry listening to one former resident of an orphanage (who, of course, wasn’t actually an orphan) describe how at first she resisted praying, but then converted. She said when she went home to see her Buddhist family she felt very uncomfortable seeing them practising Buddhism.

I just felt so sad that not only had she been raised separately to her family, and also had been coerced into yet another separation from them by changing her religion. I think these kind of orphanages need to be investigated too.

Orphanages are not right as they institutionalize children and lead in child rights abuses in Tanzania. However govt and CSOs are deinstitutionalizing children within negotiated legal and operational systems albeit slowly due to capacity and resource challenges.

The lens to look at it is from the child rights perspective and all “in the best interests of the child” as that is the RIGHT THING. Challenges to integration of children with/in ‘families’ will always exist..and am not going into the causes as most as context specific.