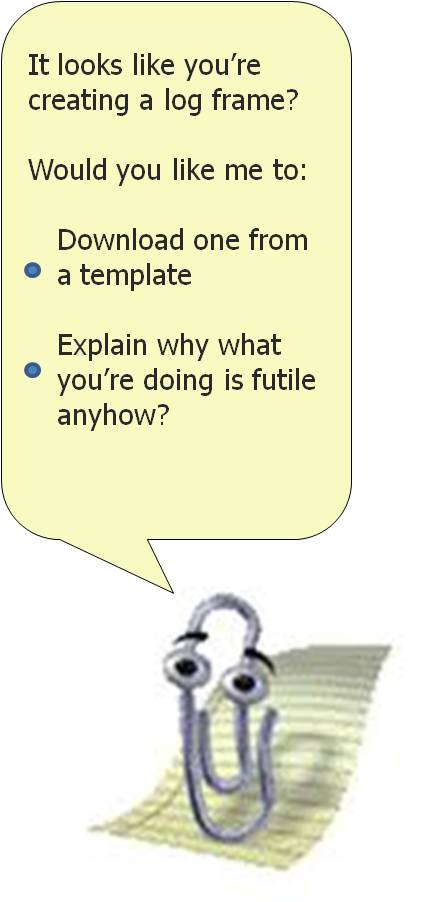

I’ve always thought the main problem with futurists is that they have too much faith in the future; that they’re overly inclined to see bold and dramatic changes when in reality an awful lot stays the same, or shifts only incrementally. This is why only a few decades ago science fiction movies as well as books by semi-serious authors painted pictures of an imagined 2011 that was nothing like the one we actually got. Instead of teleportation we ended up with email. Instead of sentient robots, we got the Microsoft Office Assistant.

If I were to venture a partial critique of Todd Moss’s excellent talk and blog post from a couple of months back (as well as similar comments from academics like Andy Sumner), it would be along these lines. The world of aid will change, but I’m not so sure it will change that much. And those changes that do occur will probably be the ones we least expect (really, who on Earth would have ever anticipated Twitter?).

Moss is almost certainly correct, for example, that the future will see far fewer poor countries by today’s measures of global poverty. But it’s worth remembering that these measures themselves are very, very low. By any reasonable criteria, 20 years from now there will still be plenty of poor countries and the majority of the world’s people will live in poverty. As Lant Pritchett has pointed out [pdf], global poverty lines are almost an order of magnitude lower than those used in OECD countries, even taking into account differences in cost of living. And poverty lines in OECD countries are themselves far from generous. We are a long, long way away from a world free of poverty, and the income gap between the world’s wealthy countries and countries in the developing world will remain for years to come (have a look here to see this graphically) — as will the moral case for aid. Possibly the rising wealth of poor countries will weaken the case for aid as a tool to fill financing gaps and promote economic transformation. Which, in turn, may mean that the main use for aid will be in providing a ‘safety net’ of sorts that affords health and education services to the least fortunate people living in developing countries. Possibly it will also mean a need for increased aid to governance programmes that help growing states to build the capacity to fund and implement such safety nets themselves. But, in an aid world where the last decade has been filled by talk of good governance and the MDGs, this really doesn’t sound like change.

Likewise, Moss is most probably correct in his prediction that aid budgets will cease to grow as fast in the future as they have over the last decade. But whether this really counts as an end of an era is less certain: OECD country aid budgets have shrunken in the past, but these reversals have themselves reversed with time. It’s likely that aid flows will contract in the fiscal wake of the Global Financial Crisis but I think it’s much less likely that this will be permanent. As long as the need remains, so too will lobbying and pressure to provide aid to help.

Where I do think Moss is right is in his prediction that new donors (both state and non-state) will be an increasing presence in the world of aid. In the Pacific, for example, best available estimates [pdf] already suggest that China is one of the largest donors to the region. Globally, other states such as Brazil and India are also increasingly becoming players. The geography of aid is unavoidably shifting.

Quite what this means is less certain though. Whether the aid offered by new donors will be good, ambiguous, or harmful all depends on practicalities and political economy. For aid provided by non-government actors outcomes will depend on prosaic practical choices made when disbursing largess: will they choose vertical funds or more systematic approaches? How good will their Monitoring and Evaluation practices be? And so on.

For new government the key question will be how the tussle between vested interest, national interest and enlightened self interest plays out. As I mentioned in my last post, the aid programmes of many developed countries have improved significantly over the last two decades. These improvements have been the product of a range of factors including a changing geo-strategic environment and the development of international norms, but possibly the most important ingredient in the improvements has been the rise of an active and effective donor country civil society that has demanded aid be given morally and effectively. The obvious question which stems from this observation, when talking about the aid programmes of countries like India, China and Brazil, is whether a similar domestic ‘good aid’ lobby form in these countries, and how successful will it be.

I don’t pretend to know the answer to this but I expect it is important. Without domestic lobbying around quality of aid it’s likely that a lot of aid given by new donors will be focused on geo-strategy or captured by vested interests. It’s even possible that the rise of new donors uninhibited by the need to give aid well will lead to traditional donors becoming returning to their geo-strategic habits of old (which, of course, never fully went away).

So if you were to ask me, I’d say the biggest change coming to the world of aid is a remarkably uncertain one. Maybe new donors will mean new money and new ideas. Or maybe they’ll mean familiar mistakes and familiar misdeeds. If we’re really unlucky, the future of aid may end up looking an awful lot the past.

Terence Wood is a PhD student at ANU. Prior to commencing study he worked for the New Zealand government aid programme.

Leave a Comment