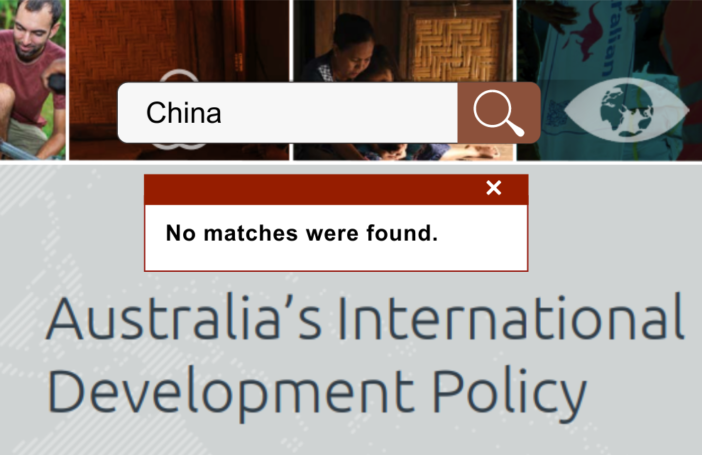

Launched in 2023, the Australian Government’s International Development Policy has been pointed to as signalling a number of shifts in the Australian aid program – perhaps most notably towards more locally-led development. It also signals an under-acknowledged reorientation of Australia’s strategies for achieving development.

While remaining firmly committed to state-building as a way to support the capacity of states to deliver, the policy also points to a shift towards enabling civil society and supporting local leaders and coalitions to drive change in their own countries. These strategies should be understood as “bets” on how development happens – they propose different ideas about where change is likely to come from. Recognising them as different strategies for change would prompt DFAT staff and those implementing its programs to think about how change happens and how these different approaches might be brought to bear in a given context and programming area. So, where is state-building, versus civil society, versus local leaders and coalitions, likely to drive development? And in what combination?

At the recent Development Intelligence Lab event celebrating the one-year anniversary of the policy, these three different strategies for development were flagged, with some suggestion that they all play a role and are mutually supportive. While intuitively appealing, this is not always the case.

There are, of course, interrelationships and overlaps between different strategies for change and sometimes they push in the same direction. For example, building the public financial management capacity of the state while supporting civil society advocacy on accountability can go hand in hand with more responsive public spending. But it is not the case that all strategies always contribute equally to change. A case in point is where state-building efforts to train and equip police services undermines the rule of law by strengthening a predatory service that impinges on the rights and safety of the citizens they are meant to protect. In such cases, change pursued through state-building is in tension with change pursued through support to civil society. Not all change strategies are complementary or cumulative.

Thinking more explicitly about different approaches to change as strategies or bets is useful in uncovering the implicit biases we operate with to understand how change occurs. It is widely recognised that developmental change has historically been driven by a range of factors – rather that a single “root cause”.

For instance, critical junctures are defining moments of change that disrupt the status quo, such as natural disasters, election results, or conflicts. The 2022 coup in Myanmar serves as a prime example of such a juncture. In contrast, social movements represent the gradual efforts of groups exercising agency to challenge and dismantle structures over time, much like the civil rights movement. Technology can also play a transformative role, with advances like the contraceptive pill leading to shifts in family structures, workforce participation, and household power dynamics.

Leadership can be pivotal in driving change, whether at a national level, like President Paul Kagame’s controversial transformation of post-genocide Rwanda, or at a community level, where religious leaders can galvanise communities to end harmful traditional practices. Lastly, coalitions of actors with shared interests can propel change, as seen in the Coalitions for Change program in the Philippines, where issue-based groups work together to reform governance policies. This list is not exhaustive – but points to some of the commonly recognised drivers of change. We all operate with preferred mental models about how change happens – some of us are naturally drawn to social movements as drivers of change; some by the power of technology. But the point is that we need to be alert to the many possible ways in which change might happen in different contexts and think strategically about how development assistance can contribute. This means recognising our own preferred mental models and thinking more openly about approaches to development as strategies for driving change.

Critical to conceiving of these as different bets for how development is achieved is developing a framework for capturing learning about what works, for who, where, and why. This goes well beyond the program-level monitoring, evaluation and learning that attracts considerable investment, to embedding a curiosity for learning about how change happens within DFAT and its program implementation. What is needed is a higher-level framework that can capture which strategies are effective in which contexts (both in countries and programming areas), identifies who benefits from these strategies, and uses research to understand the outcomes. Such an approach would require thinking through the strategies for change that are embedded within investments, as well as across country and thematic portfolios. This would go a long way to making future policy commitments and program planning more evidence-based in its selection of strategies for change – so that these are done intentionally rather than by default.

If development is fundamentally about understanding and navigating how change happens, then getting clearer on the strategies we are testing and what we’re learning about them is crucial. We can distil a number of these strategies from Australia’s International Development Policy and would do well to treat them more explicitly as distinct approaches for driving change.

Thanks for the comments. Peter, in response to your question about how the Act applies – I imagine that DFAT can be in compliance with this by undertaking the existing monitoring and evaluation steps that it does. The problem is that these are focused on ensuring effective use of taxpayer money for a particular intervention – and not on learning in aggregate about ‘what works’ (and what does not) in supporting developmental change across DFAT’s portfolio. This latter question to my mind has the much bigger ‘value for money’ pay off but does not neatly fit compliance demands as per any laws and policies. It requires us, therefore, to have an interest (and make an investment) in learning that goes beyond the minimum required but potentially with a big pay off.

Many thanks for your follow-up comments, Lisa

Having been involved in lobbying on foreign aid for 38 years, I have seen many “promises” and statements of “good intentions” and significant “strategic plans” made by the federal government and its various Ministers for Foreign Affairs.

However, DFAT’s “Performance Reports” relate to annual progress in countries:

https://www.dfat.gov.au/publications/development/development-program-progress-reports. Not eventual outcomes – usually requiring several years.

In 1990 at the World Summit for Children, Australia committeed to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, where Section 38(4) remains highly-relevant to our war-torn world:

“4. In accordance with their obligations under international humanitarian law to protect the civilian population in armed conflicts, States Parties shall take all feasible measures to ensure protection and care of children who are affected by an armed conflict.”

Which Australia did in the 1990s, in its participation in peace-keeping missions in places like Cambodia, Somalia and Rwanda. With military support of civilians in northern Iraq (under Operation Habitat) and later in East Timor. But now ?

When there are elements in Australia who say all aid should be abolished while we have poverty in Australia.

In all those years since 1986, I have never heard a Minister for Foreign Affairs say something like:

“Remember that aid program which Australia started X years ago ? It was intended to achieve (name objectives and targeted groups) and we spent $Y million dollars on it. I am now very pleased to announce that it has demonstrably achieved the following…………………… Australia’s foreign aid and your tax dollars make a difference to reducing extreme poverty and improving our world.”

According to the World Bank: “Around 700 million people live today in extreme poverty – they subsist on less than $2.15 per day, the extreme poverty line. After several decades of continuous global poverty reduction, a period of significant crises and shocks resulted in three years of lost progress between 2020-2022.”

Unimaginable in Australia. But where Australia can make a difference.

So: comments on these comments by PNG’s Minister for National Planning Ano Pala :

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-09-20/png-minister-warns-australian-aid-may-be-wasted/104373828

“The ongoing discussions surrounding boomerang aid and concerns about funds being switched, withheld in Canberra and absorbed by Australian management contractors and consultants, emphasises the importance of ensuring tangible outcomes for the PNG citizens.”

Mr Pala asked Australia to “allocate resources that directly benefit the community, rather than focusing primarily on sectors that incur high administrative and consultation costs”.

Thanks for publishing. As a PS: how do Sections 38 and 39 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 apply to our aid budget. More especially to Section 38 that applies to DFAT (too):

38 Measuring and assessing performance of Commonwealth entities

(1) The accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity must measure and assess the performance of the entity in achieving its purposes.

(2) The measurement and assessment must comply with any requirements prescribed by the rules.

39 Annual performance statements for Commonwealth entities

(1) The accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity must:

(a) prepare annual performance statements for the entity as soon as practicable after the end of each reporting period for the entity; and

(b) include a copy of the annual performance statements in the entity’s annual report that is tabled in the Parliament.

Note: See section 46 for the annual report.

(2) The annual performance statements must:

(a) provide information about the entity’s performance in achieving its purposes; and

(b) comply with any requirements prescribed by the rules.

I believe Lisa has made an important distinction between the pursuit of strategies we might find desirable as opposed to what may work within a given context on the ground.

Her statement that critical to conceiving how development is achieved is developing a framework for capturing learning about what works, for who, where, and why is essential.

If, as she posits, development practice is fundamentally about understanding how sustainable change happens then getting a clear picture of how our strategies do or do not resonate within a given socio-cultural milieu is critical. I would suggest that is a far more nuanced process than is presently admitted to.

For example, in a strongly patriarchal setting it might be one thing to promote a GEDSI agenda through local women’s groups (an approach that might attract a tick in a MEL log frame). Quite another to promote the economic empowerment of men that by design simultaneously empowers women and enhances the delivery of the essential services they need.

A circuitous route towards the same objectives but in a more acceptable and potentially sustainable way. And if this approach necessitates the inclusion of greater local agency over activities and ownership for deliverables then so be it. The real challenge, as I see it, is for agencies to have the courage of conviction in the strategies they pursue to be more post box than implementer and demonstrate that.