My first article in this three-part series summarised recent key trends in health aid financing globally. This article focuses on the growth in non-communicable diseases (NCDs) — the leading cause of death in the world — as an international development issue. I draw on a number of important reports on NCDs published in the last few months in the run-up to the Fourth High-level Meeting of the UN General Assembly on the prevention and control of NCDs and the promotion of mental health and wellbeing held in New York on 25 September. The various reports focus on the “big four” NCDs: cardiovascular diseases, cancers, chronic respiratory diseases and diabetes. (The latest findings on mental health are reported in the 2022 World Mental Health Report.)

The latest evidence shows that NCDs are not “just” an important and growing public health issue: they are also an important development challenge. That is so for several reasons. First, the latest World Health Statistics 2025 (WHS25) from the World Health Organization (WHO) notes that nearly three quarters (73%) of the 43 million NCD related deaths in 2021 (latest year available) occurred in low- and middle-income countries. An earlier, 2022 WHO report shows the increasing importance of NCDs as a cause of death as countries graduate from low- to middle-income status.

Figure 1: Deaths by cause in 2019 globally and World Bank country income classification

Source: World Health Organization 2022.

The increasing importance of NCDs is also noticeable in much of Asia and the Pacific. As just one example, Figure 2 plots the main causes of death and disability combined for Solomon Islands over the period 2011-2021. It shows that five of the top 10 leading causes of death are NCDs and — importantly — that four of those NCDs are increasing rapidly while communicable and neonatal disorders have decreased.

Figure 2: Solomon Islands – what causes the most death and disability combined?

Source: Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation 2024

A second reason why NCDs are a development challenge is that 82% of the 18 million “premature deaths” (deaths before age 70) occur in low- and middle-income countries. Premature deaths — many of which may be preventable — have significant social and economic costs at both the national and household level. Premature deaths are a particular challenge in the Pacific, even by global standards. The latest WHO NCD Progress Monitor 2025 assessed the rate of premature deaths of 193 countries for which data is available. The five highest rates of premature death in the world all occur in the Pacific: see Table 1 below which, for brevity, reports on all countries with premature death rates of 30% or above. (PNG, Lao PDR, Tonga and Pakistan fall just outside 30% but nevertheless have high rates of premature deaths of 29%, 27%, 27%, and 26% respectively. For context, Australia and New Zealand have rates of premature deaths from NCDs of 8% and 10% respectively).

Importantly, Pacific Island countries, in particular, often have insufficient data to accurately plan responses to NCDs. The Progress Monitor shows that for 10 countries globally there is simply “no data” available on NCDs including number of NCD deaths, percentage of deaths from NCDs and percentage of premature deaths from NCDs. Of those ten countries, six are in the Pacific: Cook Islands, Marshall Islands, Nauru, Niue, Palau and Tuvalu. With small total populations — Niue has an estimated population of less than 2,000 — it is a missed opportunity to generate evidence about premature NCD related deaths given the impact such deaths have at an economy-wide and also at a household level.

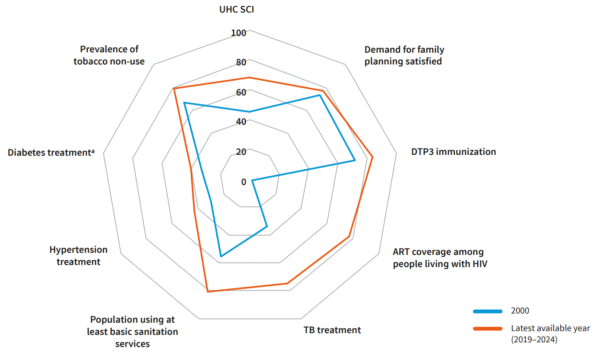

A third reason why NCDs are a development challenge is that they are often expensive to treat over long periods of time. An older, 2011 report by Harvard and the World Economic Forum, estimated that “over the next 20 years, NCDs will cost more than US$ 30 trillion, representing 48% of global GDP in 2010, and pushing millions of people below the poverty line”. That is partly because NCDs often impose new, different, longer duration, and more complex and expensive demands on public health systems in developing countries. Many health systems in developing countries were designed — and still function — to respond primarily to the earlier, and different, challenges of communicable diseases. Yet globally there has been relatively little progress in expanding health coverage for the prevention and treatment of NCDs as part of the Universal Health Coverage (UHC) agenda. Figure 3 from the WHS25 report (page 42) shows clear progress globally in expanding UHC for family planning, basic sanitation and the prevention and treatment of important communicable diseases between 2000 (blue line) and 2024 (red line). But there is much less progress for expanding treatment for diabetes and hypertension over the same period.

Figure 3: Changes in Universal Health Coverage globally

Note: ART: Antiretroviral therapy; DTP3: diphtheria, tetanus toxoid and pertussis vaccination; TB: tuberculosis. *Diabetes will be a UHC tracer in the next round of reporting. Source: World Health Statistics 2025.

A fourth reason why NCDs are a development challenge is the pronounced mismatch between NCD prevalence and impact in developing countries and the level of international aid directed to NCDs. The previous article in this series noted that total development assistance for health (DAH) has fallen to levels not seen for over 15 years, to US$39.1 billion. But within that shrinking DAH, international aid for NCDs has always been disproportionately low: an estimated 82% of NCD-related premature deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries (see above) yet the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation states funding for NCDs has generally been less than 2% of total development assistance for health.

A fifth and final reason why NCDs are an international development challenge is the noticeably poor progress towards achieving Sustainable Development Goal 3 which targets “good health and wellbeing”. As the WHS2025 notes, “Neither the world, nor any one region, is on track to meet the SDG3 target of reducing the risk for premature mortality by one third by 2020. The South East Asia region, where premature NCD mortality has remained high since 2000, is at greatest risk of missing the target.” (page 24)

Fortunately, there are several documents explaining how to prevent and treat NCDs in ways that are affordable, practical, cost-effective and even cost-saving: see here, here, here, here, and here. And the Task Force on Fiscal Policy for Health 2024 report finds that a 50% increase in the price of three unhealthy products (tobacco, alcohol and sugary drinks) via taxation “could avert over 50 million premature deaths over the next 50 years, 88% of them in low- and middle-income countries”. WHO estimates such taxes could generate US$1 trillion in domestic revenue that could be used in the health sectors of developing countries that are now facing large international aid cuts globally.

A third article in this series will present latest trends in the growth of diabetes, a particular challenge for countries in the Pacific.