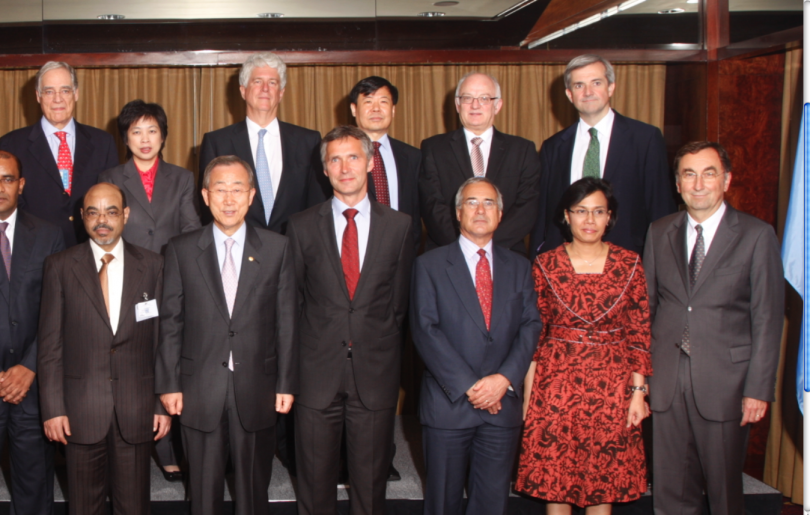

(Editor’s note: Bob McMullan recently served on the UN Secretary General’s Advisory Group on Climate Change Finance. In this article, he reflects on the contributions, lessons and next steps.)

It was both a privilege and a pleasure to serve on the Secretary General’s Advisory Group on Climate Change Finance (AGF or Advisory Group). As an intellectual exercise it was challenging and as a public policy exercise it was stimulating.

The brief was nothing if not ambitious. Not to just to find $100 billion but to do so in a way which was capable of generating such flows annually while meeting the Secretary General’s criteria: revenues; incidence; equity; practicality; acceptability; additionality and reliability.

The detail of what was considered and what was decided is available on the Advisory Group’s final report.

Having seen some of the initial response and commentary, including on the Development Policy blog, there are a number of questions and lessons beyond the substance of the report itself.

Some of the interesting questions now are:

- What contribution did the Advisory Group make to the overall challenge before the UNFCCC?

- Are there lessons to learn in dealing with other multilateral negotiations?

- What are the next steps?

Contribution and the Lessons

1) I believe that in the long term one of the major contributions of the Advisory Group will be the depth, breadth and quality of the technical background papers. They are not of uniform quality, but taken as a whole they constitute a body of analysis which negotiators and others will be able to draw on with confidence.

2) More immediately the AGF Report highlights four fundamental elements of any package.

- Build on existing measures, including fast track commitments and existing bilateral, regional and multilateral efforts.

- Develop new measures, preferably those which have both carbon efficiency and revenue benefits, most notably the proposed charge on international transportation.

- Generate private sector flows, not just for the financial resources but also for the associated entrepreneurial and technological benefits that tend to follow a price on carbon.

- Notwithstanding the domestic political difficulties in several countries, including Australia, the Advisory Group’s work reinforces the fact there is no solution to the climate change challenge without a price on carbon. It is not a question of whether this should be done but rather how soon and how.

3) Less exciting but perhaps equally important, the Advisory Group highlighted not only the possibilities but also some limits to what is realistically possible.

Some of the proposals that came forward were ill-founded, some were meritorious but unlikely to be implemented within even a 2020 timeframe, and others would not have the necessary support from governments.

The proposition to divert fossil fuel royalties to the climate change financing task was double-counting at best or simply misconceived. (This should not be confused with the much stronger case for the abolition of fossil fuel subsidies.)

The proposed carbon export optimisation tax presented serious challenges in terms of economics, but also with regard to the impact on developing countries. It also lacked support.

The possibility of utilising SDRs from the IMF to generate “Green Funds” had powerful support from intelligent people, but lacked support from governments with the necessary IMF voting power.

The International Transactions Tax had, and retains, supporters within the Advisory Group. My concern with this proposition is not the economics. Rather, my concerns are what I still see as the impossibility of fairly and effectively implementing the measure without universal application and the inevitability that some, if not all, of the funds that may be generated from any such measure would be used for non-climate change purposes such as future banking crises or fiscal consolidation. The Report keeps this option open for interested countries which wish to proceed unilaterally or regionally.

4) A closely related contribution of the Advisory Group was to challenge, or dispel, a few myths or misconceptions, for example: that there is $100 billion or more to be had from developed country budgets; that any measure requiring international coordination will be quick or easy; that budget funds are more reliable, more predictable or secure than private flows.

5) The Advisory Group’s Report should strengthen the hand of those seeking to make a constructive contribution within the UNFCCC negotiations, for example Prime Minister Meles and President Jagdeo. Giving them something to put before their counterpart Heads of State and Heads of Government was a significant influence on my views.

6) The Report should add to the recognition that the financing issue is not just a supply side question, there are significant effective demand questions to be considered also. It will be impossible to maintain support for raising such vast amounts without confidence that the money will be effectively accessible to small states and states with weak bureaucracies – particularly for adaptation. This raises the issue of ‘special windows’ at the regional development banks and a role for UN agencies in assisting applicants.

7) A lesson that the experience of the establishment and operation of the Advisory Group may illustrate is that such mechanisms might be used to break down what appears to be becoming an intractable task of comprehensive international negotiations into manageable chunks at which technical expertise and specialised knowledge might be thrown to generate building blocks for the larger task.

Next steps

If developed and developing country governments recognise that there is no $100 billion p.a. without some action on international transport fuels they could drive activity within the International Civil Aviation Organization and the International Maritime Organization to resolve the complex issues involved. This task will be difficult and is likely to take a long time, but the sooner we start in earnest the sooner it will be completed.

Most of the next steps from here depend upon the broader UNFCCC negotiations not the Advisory Group. We were able to show what was possible, only the governments concerned can make it happen.

The Advisory Group has established that if the political will exists to resolve the other issues with regard to the UNFCCC negotiations the financial aspect can be resolved. It is challenging but feasible.

Bob McMullan is an Adjunct Professor at the Crawford School. He recently served on the UN Secretary General’s Advisory Group on Climate Change Finance (AGF). From November 2007 to August 2010, Bob McMullan was Australia’s Parliamentary Secretary on International Development Assistance.

With all due respect, Prof. McMullan, the AGF and the UNSG are dreaming. $100 billion p.a. will materialize only from the Private Sector, if ever, at the expense of more GHG emissions. Carbon markets are the cover up, and the benefits are gained only in the Stock Markets. The AGF should have looked at more realistic approaches, icluding a

o funds scenario. To me, the most realistic statement in the above report under point 3 is: The possibility of utilising SDRs from the IMF to generate “Green Funds” had powerful support from intelligent people, but lacked support from governments with the necessary IMF voting power. Prof McMullan rightfully states that intelligent people and governments are not the same.

Meetings in Bali, Cancun and other exotic spots will continue for ever thanks to growing GHG emissions. If P.M. Meles wants to reduce GHG emissions, he should stop oil export from Norway for one month annually instead of paying Indonesia, Brazil and President Jagdeo.

Dr. H. El-Lakany, Adjunct Prof. Univeity of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. Former ADG/Head of the Forestry Department, UN FAO, Rome.

‘If developed and developing country governments recognise that there is no $100 billion p.a. without some action on international transport fuels they could drive activity within the International Civil Aviation Organization and the International Maritime Organization to resolve the complex issues involved. This task will be difficult and is likely to take a long time, but the sooner we start in earnest the sooner it will be completed.’

I absolutely agree with this in principle, but the practicalities of driving it through the IMO are a real sticking point. The argument goes that the IMO process is bogged down in the same way that the UNFCCC process is, because parties which are opposed to global agreement in the latter see the former as having the potential to set an unwanted precedent, and act accordingly… However, the bunker tax proposals are mainly looking at generating decarbonisation funds for the shipping industry which doesn’t have the same appeal as this proposal.