Ideas are central to changing aid policy goals. In fact, it is the ideas enshrined in policy goals that advocates aim to either change or protect. As I outlined in the previous post in this series based on my doctoral research, individuals behaving entrepreneurially were necessary features in achieving policy goal change in New Zealand (NZ) in 2001 and 2009. Yet, these individuals did not act alone. They were part of ideas-based networks.

Policy change scholars show that individuals and organisations across government and society come together in various ways to change policy (Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith 1993; Rhodes and Marsh 1992 [paywalled]; Dowding 1995 [paywalled]; Kingdon 2001; Baumgartner and Jones 2009). The one thing that stood out in my research was that actors coalesced around their shared ideas, forming ‘ideas-based networks’. Below I delineate the types of ideas involved, and then describe the different types of networks that emerged in the two change cases.

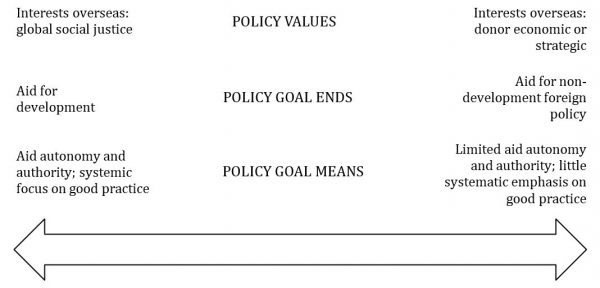

The ideas involved in aid policy goal change can be placed along continua and categorised according to their relationship to policy’s substance, as depicted in the diagramme below.

The most important ideas in aid policy goal change are deep: world views, values and beliefs. I call these ideas ‘policy values’. For aid policy, policy values include the donor government’s ideological beliefs, such as ideas about the primacy of unfettered private sector growth, the role of the state, and whether social justice or economic growth is the priority for a state’s advancement.

Aid policy values also involve how a government defines their interests overseas. I avoid the concept ‘national interest’, as it is a slippery notion. Instead, I demarcate close and distant interests. Close interests are a donor government’s short-term, self-focused foreign policy aims: ‘close’ in terms of time and geography, in that the results will be primarily felt quickly, within the donor state’s border. Distant interests are more long-term foreign policy aims, such as development, and in the first instance will be geographically achieved beyond the donor state’s border.

Policy goals can be divided into ends and means. Policy goal ends are ideas about what should be achieved with aid policy – development outcomes only, or a mixture of development and non-development foreign policy outcomes. Policy goal means are how a donor will attempt to achieve policy goal ends. If a donor government wishes to achieve development outcomes with their aid then that government will give their aid programme greater autonomy and authority in relation to non-development foreign policy, and will strive to implement the best aid policy they can.

Any particular government’s approach will move along the continua at different points in time, for different countries. However, in my research it was possible to identify general trends according to whether left-leaning or right-leaning governments were in power during the two NZ policy goal changes I explored. This is related to the ideas-based networks in existence.

Actors tended to group together based on the ideas described above. In 2001, a strong, coherent network developed across government and society, comprised of NGOs, left-leaning political parties and individual private sector consultants working in international development. These actors prioritised social justice, collective action, and NZ’s role in the world as a good citizen. These were their underlying policy values, which translated into a desired policy goal ends for aid to be spent on development. This then shaped policy goal means, in that aid should have autonomy and authority in relation to non-development foreign policy, and the government should aim to implement the best quality aid policy it could.

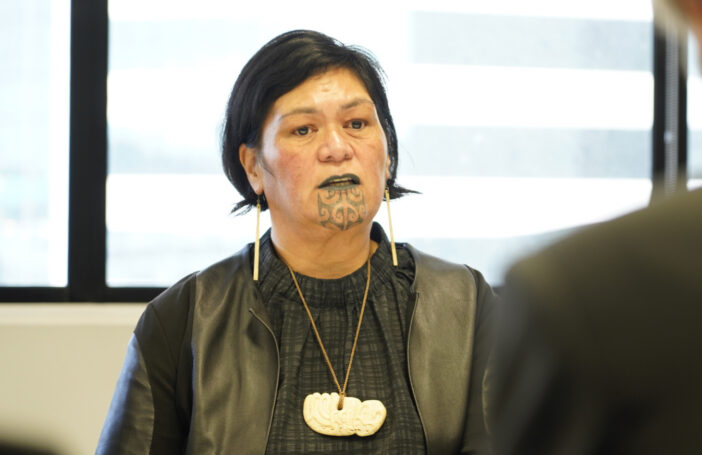

The 2009 change network was loose, centered around Minister McCully, involving individuals from the private sector and government. These actors were connected by the belief that countries develop first and foremost through the growth of their private sector, and the benefits of this will seep across a country’s economy and foster social progress. They saw NZ’s interests globally as anything that would advance NZ’s economic development, which became the number one foreign policy priority. They believed aid should be aligned with this wherever possible, and at best should achieve both NZ’s economic growth goals and another country’s development (what I label ‘dual benefit aid’), or should simply advance NZ’s economic goals. This was all part of the ‘NZ Inc’ approach to NZ in the world – branding, advertising and selling NZ overseas in a coherent and coordinated way, including aid.

Unlike in 2001, a robust network took action to prevent change in 2009: the same ideas-based network that worked to achieve change in 2001. Some of the individuals were even the same, such as Phil Twyford, who was Oxfam’s Executive Director when NGOs were setting the change agenda in the late 1990s and in 2009 was in parliament as the Labour Party opposition spokesperson on aid. The Council for International Development (CID) spoke out against the 2009 changes, and member NGOs launched a ‘dontcorruptaid’ campaign. However, even with a cohesive network fighting to protect the status quo (as opposed to isolated attempts in 2001), aid policy goal change was decided in April 2009, only two months after change opponents learned of the proposed change.

This point highlights timing issues and how aid advocates need to think far ahead, understand the various ideas at play, and plan for points in time when change can best occur. This relates to knowing the rules of the system, a point I discuss in the next and final post.

Jo Spratt is an ANU PhD candidate studying NZ aid policy. This post is the second in a three-part series based on her PhD thesis; read the first post here.

Jo, this is super fascinating stuff. I think ‘ideas-based networks’ can be very powerful (in certain contexts) for the setting of aid and policy priorities. My Doctoral research (completed 2014) explored the role of ‘epistemic communities’ in the construction of policy choice in Pacific island countries. My research found that policy entrepreneurs within key institutions were key to setting the terms of debate about appropriate policy, particularly when those individuals generated a new body of knowledge (through publication), and worked with others as part of a transnational network (thus participating in a normatively powerful ‘epistemic community’). Perhaps we can share our ideas ‘off-line’. Wes