In 2007, the then Minister for Foreign Affairs Alexander Downer claimed that gender equality was “fundamental” in Australian aid’s efforts to lift people out of poverty. In 2023, Pat Conroy, the Minister for International Development and the Pacific, wrote that he was “proud that, as a partner”, Australia was prioritising gender in its development work. In between, senior politicians such as Julie Bishop and Julia Gillard emphasised the importance of gender equality for Australian aid. Gender has, nominally at least, been central to Australian aid for more than 15 years.

Despite this, until recently it has been hard to build an accurate, quantitative picture of the types of places and projects that Australia focuses its gender equality aid on. It has also been hard to get a sense of the outcomes that Australian aid projects have for women.

It should have been easy: each year Australia tells the OECD which of its projects are “principally” or “significantly” focused on gender (read the definitions). And in performance assessments – which are conducted annually for all projects over $3 million, and also at project completion – DFAT requires staff to assess the difference projects have made to, “gender equality and empowering women and girls” (since 2021 impacts on disabled people have also been coupled with gender in this assessment).

However, until 2017 there was a lot of flexibility in how projects were classified in OECD reporting. And until 2018, systems for validating staff members’ own assessments of the gendered impacts of the projects they were managing were weak.

In 2017, however, Australia adopted more stringent guidelines in its OECD reporting. And after 2018 DFAT began using external contractors to review staff members’ own claims about project efficacy in final performance reports. This led to a significant drop in reported performance in final project assessments. Reported outcomes for women also fell.

The resulting data are still not perfect: performance assessments are not impact evaluations, and OECD reporting still contains wiggle room. Yet the data are now good enough to learn about the focus of Australian aid for gender equality and the outcomes that Australian aid has for women.

In my new Development Policy Centre Discussion Paper, I take advantage of this to look carefully at Australian aid and women. The paper is technical, but in this blog I will provide a simple summary. Readers with an interest in statistics should note that in this blog I describe bivariate relationships. In the paper itself I report on the findings of regression models that control for a suite of potentially confounding variables. All of the findings in this blog also exist when controls are added. All findings reported here come solely from years with better quality data.

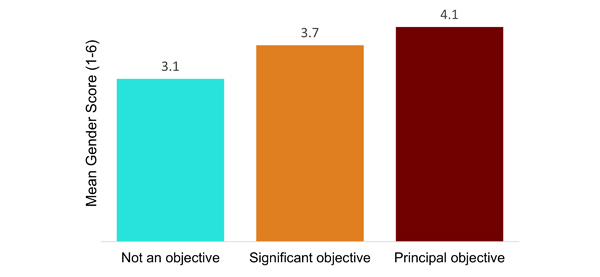

First, a commonsense finding. As the chart below shows, projects with an explicit gender focus have better reported outcomes for women. That may sound obvious, but it’s worth emphasising: if you focus aid on gender equality, it’s more likely to be beneficial for women.

Figure 1: Reported project outcomes for women based on whether projects had a gender focus or not (2019-2022 data)

Source: Development Policy Centre Discussion Paper 106

The second finding is more of a puzzle: a lower share of Australian aid projects have a gender focus in the Pacific than in the rest of the world. It’s hard to see why this should be the case. The Pacific is central to Australia’s aid efforts and the region’s gender issues are well documented.

Figure 2: Gender focus of Australian aid: the Pacific and elsewhere

Source: Development Policy Centre Discussion Paper 106

The third finding is also intriguing: Australian aid projects are less likely to have a gender equality focus in countries where women’s empowerment is lower. This finding comes with a few caveats. My measure of women’s empowerment is a proxy: the share of countries’ parliaments that are women. It’s not perfect, but it’s the only measure with full data for the Pacific. And the measure is correlated with the big global gender indices. The measure is imperfect, but usable.

Also, Australia isn’t much less likely to focus gender equality aid on countries with lower women’s empowerment, and the finding isn’t always statistically significant (see the Discussion Paper). Nevertheless the finding is interesting: Australia doesn’t focus its gender aid most where need is greatest. If anything, it does the opposite.

Figure 3: The gender equality focus of Australian aid compared to levels of women’s empowerment

Source: Development Policy Centre Discussion Paper 106

Source: Development Policy Centre Discussion Paper 106

One possible reason why Australian aid is more likely to have a gender focus in countries where women’s empowerment is higher could be because its projects’ outcomes for women tend to be better in countries where empowerment is already higher. The effect is not huge, but if there’s relationship between existing empowerment and projects’ outcomes for women, on average it’s positive.

Figure 4: Relationship between already existing women’s empowerment and aid projects’ outcomes for women

Source: Development Policy Centre Discussion Paper 106

Quite possibly, the relationships associated with women’s empowerment don’t reflect conscious choices by the Australian aid program. But they do raise an interesting question: should Australia concentrate aid for women on places where it’s needed most, or where it’s most likely to work?

There’s more in the Discussion Paper. But there’s also much more to be learnt. By improving its data on aid and women Australia has given itself – and the broader development community – a valuable chance to learn.

Disclosure

This research was undertaken with the support of the The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The views are those of the author only.

Thanks Terence for this work! Very interesting and helpful.

Thank you Ceridwen!

Perhaps another explanation for the lesser gender focus in countries where women’s empowerment is lower is that aid activities are supposed to be by mutual agreement between donor and recipient countries. Aid activities are not supposed to involve donors tromping over local sensibilities, which may include male counterparts being resistant to gender-based activities. Clearly, this is a conundrum with no easy solution, although one may be to include in project designs NGOs that do happen to implement gender activities.

Sorry Gerard, I don’t know why, but I didn’t receive the usual email that notifies me when someone comments on one of my posts.

I don’t know if it explains the entire relationship, but your comment makes a lot of sense, and it’s something I hadn’t thought of.

Thank you for sharing the insight.

Terence