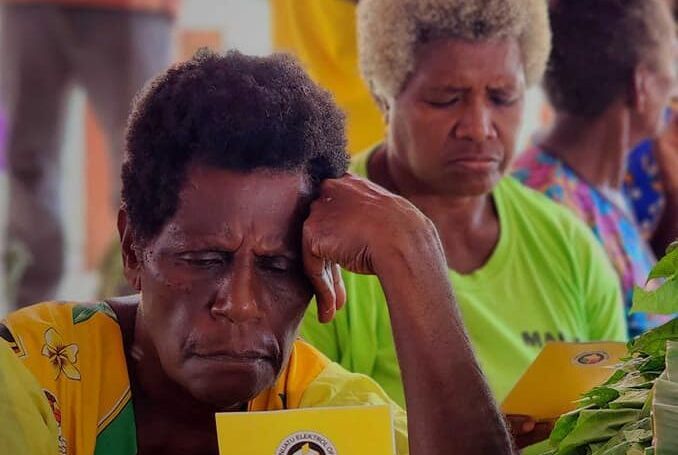

Vanuatu has had three different prime ministers since 4 September, and weathered several court challenges as politicians and parties battled for parliamentary supremacy. Vanuatu’s citizens have expressed their frustrations via social media, national Press Klab and on the streets, with more than 150 people marching to Parliament House to table a petition from over 1,800 people demanding passage of proposed political integrity bills to mitigate continued instability.

The impact of political instability is widely felt: stalled government decision-making and service delivery; deferments of key legislation by the parliament; and loss of public confidence in political leadership.

On 7 November, Prime Minister Charlot Salwai faced a fresh motion of no confidence, impacting anticipated parliamentary debate on political integrity bills and amendments, resulting in withdrawal of all government-sponsored bills. Significantly, the withdrawn bills included a bill for the Political Parties Registration Act, a new bill for the Electoral Act, and proposed amendments to related laws including the Decentralisation Act, the Charitable Association (Incorporation) Act and the Municipalities Act. Together with previous reforms of the Ombudsman Act, Leadership Code Act and the 2016 passage of the Right to Information Act, these represent and progress previous governments’ attempts at political integrity reform.

The proposed bills are basic, and critics suggest they need more work, but they are an essential step forward for Vanuatu’s democracy. In particular, a new Political Parties Registration Act is central to political integrity reforms, providing minimum political party accountability standards.

Propelled by a 2015 political scandal that led to the dissolution of parliament and snap elections in early 2016, the reforms were introduced by past governments to address political party registration and discipline. Two key, problematic political practices were initially targeted to curtail floor-crossing. First, MPs’ unrestricted ability to swap party affiliation at will, and second, the formation of tiny, short-term political parties without clear policy platforms. These practices are widely viewed as major drivers of political instability, entrenching political patronage and rent-seeking behaviours that disrupt good governance.

The 2016 attempts at comprehensive political party legislation to enhance political accountability – drawing on lessons from Papua New Guinea’s Organic Law on the Integrity of Political Parties and Candidates – were blocked, and a revised proposal was lodged in 2019 by the government of the day.

Responding to the public petition and an ultimatum imposed by Vanuatu’s President Vurobaravu – who is only permitted to dissolve parliament after the first 12 months – the Salwai Government re-tabled the political integrity bills, to be debated at the Parliamentary Extraordinary Session on 8 December.

This is a major milestone for Vanuatu politics. The bill for the Political Parties Registration Act proposes basic, minimum political accountability and ensures a more stringently monitored registration regime to curb the unfettered proliferation of parties. It requires political parties to be subject to registration and reporting requirements similar to those that apply to businesses or NGOs.

Currently, political parties voluntarily register as charitable associations with the Vanuatu Financial Services Commission, but this is not an eligibility requirement for standing in elections. Of the 44 political parties contesting Vanuatu’s October 2022 snap elections, almost half were not registered (although some had previously been registered but had gone into receivership at the time of the election). In terms of threshold requirements for eligibility to stand under a party banner in the October 2022 elections, registration or receivership status did not appear to have a bearing on the Electoral Office’s approval of parties and candidature.

Figure 1: Status of Vanuatu’s political parties in the October 2022 election

Source: Vanuatu Financial Services Commission

The proposed bill will mandate the Electoral Commission to regulate and administer political party registration in accordance with set criteria.

Between 2016 and 2019, the Office of the Prime Minister and ministries of Internal Affairs and Justice conducted wider policy consultations on political integrity reforms, resulting in a watered-down version of drafting language on anti-defection measures and transparency of political financing. For example, party affiliation clauses to assist with greater political stability are absent.

Our survey of 30 publicly available party constitutions shows that while the majority of the constitutions provide for disciplinary measures when members compromise the party position, these do not appear to extend to situations of possible “defection”. Nor were there any clauses binding a political party member to the party for a specified period after election to public office – this is a risk to political integrity, and something that the current bill does not specify, referencing only elected officials’ responsibilities to affiliate within 6 months if their party is deregistered. Opponents of including any further party affiliation conditions cite Articles 4 and 5 of Vanuatu’s Constitution, which state respectively that “political parties may be formed freely” and that members are allowed “freedom of movement”, in support of arguments against further qualifications in the proposed bill.

Legal requirements for transparency on political financing are also omitted in the bill. These are important not only for public accountability, but also to ensure funds have been obtained in a legal manner and do not place Vanuatu’s sovereignty at risk (for example, through foreign finance for political influence, which could constitute external political interference).

Despite these two key areas of oversight, the proposed package of political integrity reforms represents a pragmatic approach to tackling Vanuatu’s dynamic political environment since 2016. Passage of the bill would allow for iterative political settlement in a dynamic context of diverse party interests in the current 13th Legislature.

The Political Parties Registration bill and related amendment bills are not silver bullets for Vanuatu’s recent political instability, but their passage would be a critical foundational step in the current environment. If this foundational legislation passes when parliament next sits on 8 December 2023, parliamentarians will then need to look at constitutional reforms to qualify Articles 4 and 5 in relation to political party affiliation practice.

Maintaining a clear, iterative and multi-pronged approach to enhancing political integrity, that builds on incremental achievements since the introduction of reforms in 2016, would be a step in the right direction for enhanced political integrity in Vanuatu’s dynamic political ecosystem.

There are two versions of the Vanuatu Political Parties Registration Bill floating around. The one referred to in this blog is different from the one on the Ministry of Internal Affairs website (dated 7.12.23). And the critical legislation is not in this bill at all. It is in the Constitutional Amendments 17A and 17B which try to bind MPs to their political parties (17A) and to require independents to affiliate with political parties (17B). These are to be put to a referendum in May 2024.

Thank you for your comments Professor Fraenkel, it is indeed a critical time for Vanuatu in the lead up to the first national referendum on the proposed Constitutional amendments.

On the matter of versions: the blog links to the Vanuatu Parliament website for bills (as at the time), and the Vanuatu Ministry of Internal Affairs use the Facebook platform, both being official communication channels of the government – any difference in documents would need to be discussed directly with the government. Although passed by Parliament, with amendments made on the floor, the Bill has not yet been gazetted. There should soon be a consolidated “final version” that incorporates the amendments made on the floor of Parliament, and I suggest to keep tracking the official GoV sites.

The Vanuatu Political Parties Registration Bill claims in its ‘explanatory note’ that it ‘ensures a strong and sustainable party system’, but that is simply not true. It does almost nothing beyond granting a Principal Elections Officer powers to vet parties including assessing whether ‘the policy platform of the proposed political party is of national scope’ (S. 9 (1) b). It does not require candidates to be members of political parties (ie independents are allowed) and it allows groups to style themselves as ‘custom movements’ as long as they are confined to a single island. In Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, much more ambitious laws were introduced, but in neither country did they achieve their stated purpose. For coverage of the PNG and Solomon Islands experience, see https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ajph.12931, and http://hdl.handle.net/1885/311668.

An excellent review of the current situation which is affecting international trade and tourism also.

Well done 👏. ..indeed, an essential step forward for Vanuatu democracy!!

thank yu tuma.

Congratulations on a nice and sanguine piece. Given the overly alarmist debate that usually accompanies almost any issue in Vanuatu it is nice to see well reasoned pieces by people who know their subject.

It is always worth remembering that there is no correlation between political instability and development or economic growth in Vanuatu, in fact one could argue the opposite in that most of the most important reforms were actually implemented during a similar period of instability in the early 2000’s and based on more instability seen in the mid 90’s.

Secondly, from a behavioural standpoint this bill would discourage people standing as members of a party and thereby encourage people to stand as individuals (as they are allowed to do by the Constitution). We have seen this in other jurisdictions that tried something similar.

It is not always possible to legislate away a problem, As Vanuatu found with the National Disaster Management Act (which arguably creates a bigger disaster than that which it is supposed to respond to) this bill could ironically lead to more instability and not less.