Consider this thought experiment. If the provision of bilateral foreign aid overseas threatened the national interest, would it ever be provided? Surely, it must be at least a benign force or else someone would have long ago axed it?

Given this, one wonders why contemporary political leaders are falling over each other to tell us that aid will serve the national interest. Good global development is plainly in our interest. All citizens are a priori safer, richer and more stable in a world where we tackle illegal financial flows, human trafficking, health pandemics, active conflict, inequality and carbon emissions.

We live in an age where populists present a trade-off between domestic and global priorities. Fiscal pressures put a squeeze on public spending and demand concessional aid resources service multiple policy priorities. A changing geography of power means many emerging countries find an aid narrative centred on charity archaic; ‘altruistic’ is increasingly an unpalatable descriptor for an aid provider. Instead, concessional ODA is expected to lubricate diplomatic relations, trade opportunities and corporate investment.

An aid-sceptical public lends added fuel to this growing fire. The mantra of ‘aid in the national interest’ – or in some variations ‘aid as mutual interest’ – is chanted alongside, but little understood.

ODI’s Principled Aid Index

ODI’s Principled Aid (PA) Index is a digital tool meant to provide some much needed clarity on the meaning and measurement of aid in the national interest. It defines aid in the national interest as either principled, unprincipled, or somewhere in between. “Principled aid” services a donor’s interest in a safer, more stable and more prosperous world, and expresses the idea of ‘doing well by doing good.’ “Unprincipled aid” is self-regarding, short-termist and unilateral. Selfish donor motivations have been linked to inefficient and sub-optimal aid allocation decisions and lower levels of effectiveness. This may be because the possibility of a domestic return increases the likelihood of donor moral hazard, shifting attention and effort inwards.

The PA index measures principled donor motivations as reflected by how they provide aid. In this, we are inspired by a long line of empirical work conducted by political scientists that rely on aid allocation data to empirically capture and assess donor motivations.

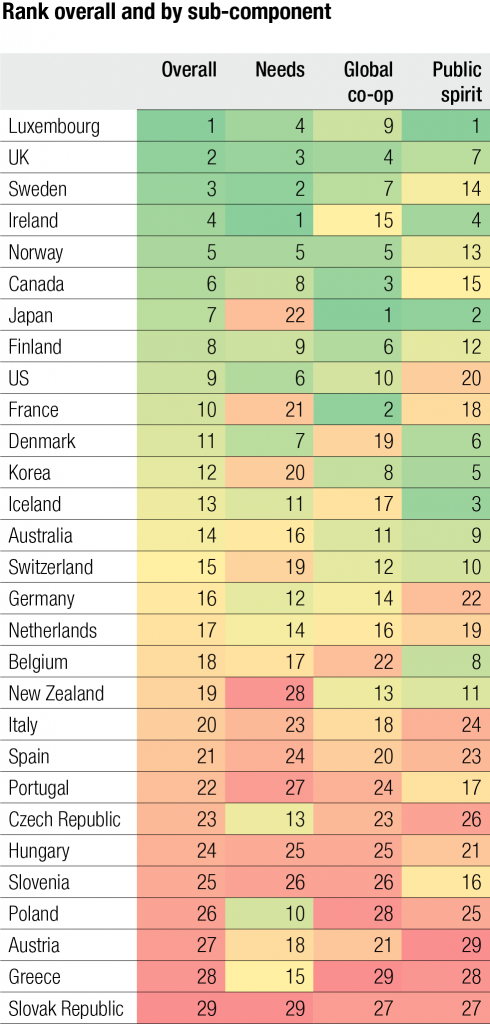

The indicators we choose are linked to the dual advancement of global and national interests in three main dimensions. Aid allocations are considered principled when they target countries where needs and vulnerabilities are significant; when they invest through channels that champion global cooperation; and when they preserve a robust public-spirited focus on development impact that constrains their own selfish behaviours, for example by avoiding tied aid. We benchmark all 29 DAC donors along each of these three equally weighted principles, coming up with an aggregate score and relative rank for each country going back to 2013. This gives us a view of how donors have performed over the last five years for which data is available (2013-2017), which can hopefully kickstart a much-needed conversation about the meaning and measurement of the national interest in foreign aid.

Principled aid: the rankings

As the table below highlights, Luxembourg tops the PA Index, followed closely by the United Kingdom and Sweden. At the bottom of the ranking is the Slovak Republic, followed by Greece and Austria. Italy is the lowest performing G7 country, with larger donors like Germany and France consistently located in the middle of the PA Index across all years.

Along with New Zealand, Japan and Korea, Australia ranks among the top half of the table on global cooperation, but on the bottom half in terms of addressing development needs. This lopsided performance may be explained by the strong regional focus adopted by Asia-Pacific donors, given the large number of relatively stable middle-income countries in the region that puts downward pressure on their score against the principle of needs-based allocation. At the same time, sizable investments in building the capacity and infrastructure for trade and climate change work in the opposite direction, resulting in higher scores on the principle of global cooperation.

Trends to act on

While individual country rankings may grab the headlines, the PA Index is arguably more valuable for the insights it offers on aggregate trends within the DAC.

For example, scores on the index increase over time, which suggests that donors are overall growing more principled in the pursuit of their national interest. However, there is simultaneously a deterioration in their public spiritedness, as measured by donors’ levels of tied aid and the relationship between aid and arms exports, among other variables. 23 out of 29 donors have experienced a drop in their public spiritedness scores between 2013 and 2017 (New Zealand is an exception here, while Australia is not), even as they continue to support countries with development needs and a functioning global commons. If principled aid is a stool with three legs, one of these is sadly rotting. Why the divergence?

One hypothesis for this paradoxical result is that while donors are increasingly aware that underdevelopment in remote parts of the world can and does have real consequences closer to home, they are also under pressure to demonstrate concrete, short-term benefits of overseas public spending to their electorates. We expect this decline in public spiritedness to only grow unless remedial action is taken.

We need to recognise that aid is in our shared national interest if it is focused on delivering solutions to real development challenges and contains the worst of our selfishness. The mantra of ‘aid in the national interest’ needs concrete principled action rather than vacuous ritual. And it needs this now.

Leave a Comment