Extractive industries transparency: News from G8 and Democratic Republic of Congo

Despite billions of dollars in revenues from oil, gas, timber and mining, many developing countries struggle to translate these revenues into better development outcomes. One of the reasons is that large revenue inflows undermine accountability of government. We’ve highlighted this issue in the context of PNG on this blog, as well as suggesting that transparency can support accountability.

Over the last couple of weeks there have been some interesting developments on resource industry transparency. The G8 recently endorsed the disclosure of extractive industry payments to governments. The G8 Deauville Declaration welcomed:

complementary efforts to increase revenue transparency, and commit[ments] to setting in place transparency laws and regulations or to promoting voluntary standards that require or encourage oil, gas, and mining companies to disclose the payments they make to governments.

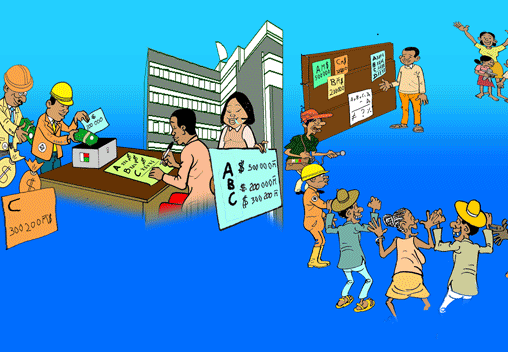

And this week we learned about an a transparency initiative in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) to make all contracts involving mineral, timber, oil and gas concessions public within 60 days of signing. These are both welcome steps towards opening up the resources sector to greater scrutiny in developing countries.

For more information or natural resource transparency see the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, the Natural Resource Charter and Publish What You Pay.

Crowdsourcing feedback on service delivery

Another dimension of accountability that we’ve explored in this blog is feedback from citizens to service providers and the potential for mobile technology to be used to crowdsource feedback on service delivery. We’re not the only ones discussing this new opportunity. The idea is gaining traction in the development community and pilots are taking place in Africa.

The Guardian’s Poverty Matters Blog has a interesting article ‘Crowdsourcing put to good use in Africa’ that discussed crowdsourcing pioneer Ushahidi and an interesting pilot program in Kenya’s education sector.

The idea behind Huduma (the Swahili word for service) is that people can send – by text, email or Twitter – reports on the performance of services in their district, explains Erik Hersman, one of the founders of Ushahidi. This will then be mapped on the Huduma site and the responsible authority will be identified.

“There will be a dashboard which will compare one district with another,” he says. “We will also layer in other information such as aid flows from, say, the World Bank. So, for example, if you pull up the profile of a school or clinic, you will have information about what aid it may have received as well as local reports on whether the teachers are turning up to work.”

The project has been six months in development for a trial in Kenya, but Hersman is impatient; it hasn’t been set up quick enough – and what has held it up has been the slow response from the Kenyan government on providing the crucial basic information, such as where schools are.

Biometric technology for transfers in development and resource-rich countries

Continuing the theme of information technology and development, Alan Gelb and Caroline Decker have written an excellent discussion paper for the Center for Global Development on how new biometrics technologies are making cash transfer programs increasingly feasible, even in difficult environments.

Cash transfers are often a good way for developing countries to address economic and social problems. They are less expensive than directly providing goods and services and allow recipients the flexibility to spend on what they need the most, but for many developing countries, the technical requirements for large-scale programs have been prohibitive. Now, however, biometric technologies have improved and become ubiquitous enough to allow the confident identification and low cost needed to implement successful cash-transfer programs in developing countries. This paper surveys the arguments for and against cash-transfer programs in resource-rich states, discusses some of the new biometric identification technologies, and reaches preliminary conclusions about their potentially very large benefits for developing countries. The barriers to cash-transfers are no longer technical, but political.

Alan and Caroline provide practical examples of biometrics from South Africa, Malawi, Pakistan, and Andhra Pradesh in India. They also discuss examples applications in post-conflict situations, drawing on examples from DRC and Afghanistan. This paper is essential reading for anyone interested in applying new technologies to development programs.

Gender and INGOs: Pretty on paper

Gender gets discussed a lot in development plans, but less often in the context of development agencies who advocate those plans. In an interesting and thought provoking piece ‘Gender and INGOs: Pretty on paper’, the Shotgun Shack blog argues that that there are double standards in many aid agencies, with women under-represented senior management positions in aid agencies. The article goes on to say:

In those agencies where there are a lot of women (eg., in countries where it’s common for women to work outside the home), the agency dynamic often closely mimics the community dynamic that the agency is all up in arms about. The men are in charge, making the decisions, and women’s participation tends towards doing all the hands-on work to implement what the men have agreed on. Men manage and decide over use of resources.

For anyone interested in gender and development it is an article worth reading and reflecting upon.

Leave a Comment