There is no part of Australian life that the current pandemic is not touching. Here are the some of the likely far-reaching implications for Australian aid.

To start with, the pandemic and resulting economic fallout have thrown the future of the aid budget up in the air. The ultimate outcome is hard to predict. On the one hand, there will be strong downward pressure on aid volumes. Domestic revenue will be weak, the deficit will be large, pressures for domestic expenditure immense. The aid budget could be slashed. On the other hand, if there are serious outbreaks in neighbouring countries, whether in the Pacific or Southeast Asia, there will be a realisation in Australia that we need to provide massive support, as we would in a natural disaster. Such a tragic – and certainly possible, if not likely – outcome would provide the basis for avoiding cuts in the aid budget, and perhaps even for an increase.

Incidentally, although Australia’s annual budget has been deferred to October, it is unclear what that means for aid. Perhaps no decision will be taken on aid volumes until then; but the government doesn’t actually need a budget to spend less aid – it can just give the order. That opens up the possibility that aid will be cut by stealth, a worrying prospect.

Such a concern might seem to support the conclusion that it would be good to have the new aid (development policy) strategy, under preparation since late last year, finalised on time in the next couple of months: if there is no budget to guide the aid program then let there at least be a strategy. But that would be a mistake. The same uncertainty that has made it necessary to postpone the budget makes an even stronger case for putting a multi-year strategy on hold. We simply don’t know what the world will look like when we come out the other end of the current crisis. And until we do, we need to focus on the here and now. It should be crisis management, full-time.

When it does come to the need for a new strategy, COVID-19 will certainly influence the way we look at things. Of all the government’s decisions in relation to aid over the last few years, the cutting of aid spending on health stands out as reckless in hindsight. It would be ridiculous to suggest that more Australian aid for health would have stopped the current pandemic. But it might have given countries affected a slightly better chance of withstanding it. Just in the last month, family planning NGOs in PNG bemoaned the latest round of Australian aid cuts inflicted on them. These are the very same NGOs that are now needed for community engagement to stop the spread of infections.

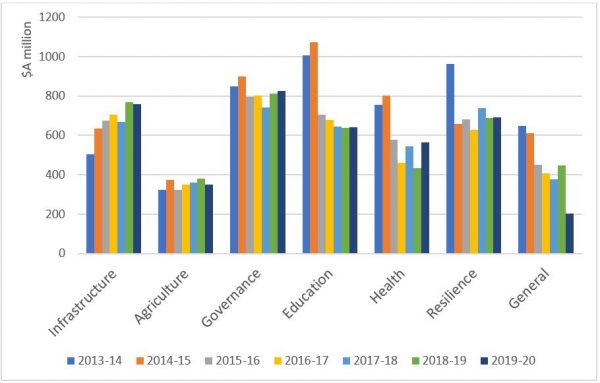

I have been drawing attention to the cuts to health for the last four years. The figure below shows Australian government aid expenditure by major sector since 2013–14. There is a small recovery in the most recent budget, due to the creation of the Indo-Pacific Centre for Health Security. No doubt the government will hail its prescience in creating that Centre. But the fact remains that aid health spending has been cut by 25% after inflation since 2013–14, whereas infrastructure spending has increased by 50%. Expect the government to come in for criticism on that point, and for a rethinking on the primacy given to infrastructure.

Expenditure by major sectors since 2013–14

The impact of COVID-19 on the aid budget may be far more complex than a shift away from infrastructure back to health. Governments in the region will need budget support to stay open. Communities may well need humanitarian assistance to stay alive. The government committed back in the White Paper in 2017 to increase humanitarian spending to $500 million, but, with the pressures of the Pacific Step-up, and no actual increase in aid, still hasn’t managed that.

Perhaps the funding for the required increase in humanitarian and budget support will come from cuts to governance, as training and advisory services are reduced due to expatriate evacuations. Despite a lack of emphasis on governance in its rhetoric, the share of spending on governance has increased under the current government, as the figure above implies. In any case, a major reshaping of the aid program is on the cards as COVID-19 and a global recession sweep through our region.

The only statement I have seen by either the Minister for Foreign Affairs or the Minister for International Development and the Pacific in relation to the current crisis is a joint one dated 3 March on support to the Pacific and Timor-Leste. It was a promising start, but was written at a time when there were no coronavirus cases in the Pacific, and is now out of date.

To most observers, including myself, the aid program has been in a state of drift for the past couple of years. Everything has been about the Pacific Step-up. The current time is not one for shaping a new long-term aid strategy, but it is an opportunity to provide a new direction, and a new sense of purpose for the aid program as a whole.

This post is part of the #COVID-19 and international development series.

Leave a Comment