The recent defence spending announcement has put the spotlight on the Australian government’s long-term defence spending plans. The 2016 Defence White Paper had already foreshadowed explosive growth in defence spending to 2025; now we know that growth will continue until 2030. The government also has a policy regarding future aid spending, with no increases to the aid budget until 2022-23 after which aid will be indexed to inflation.

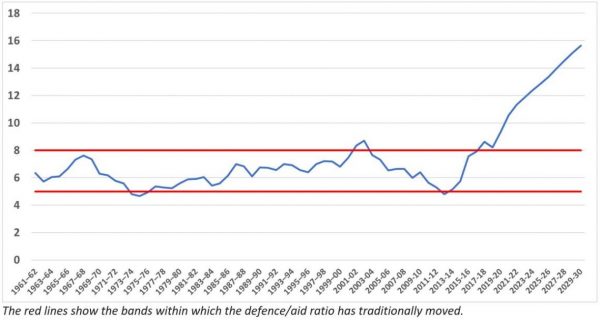

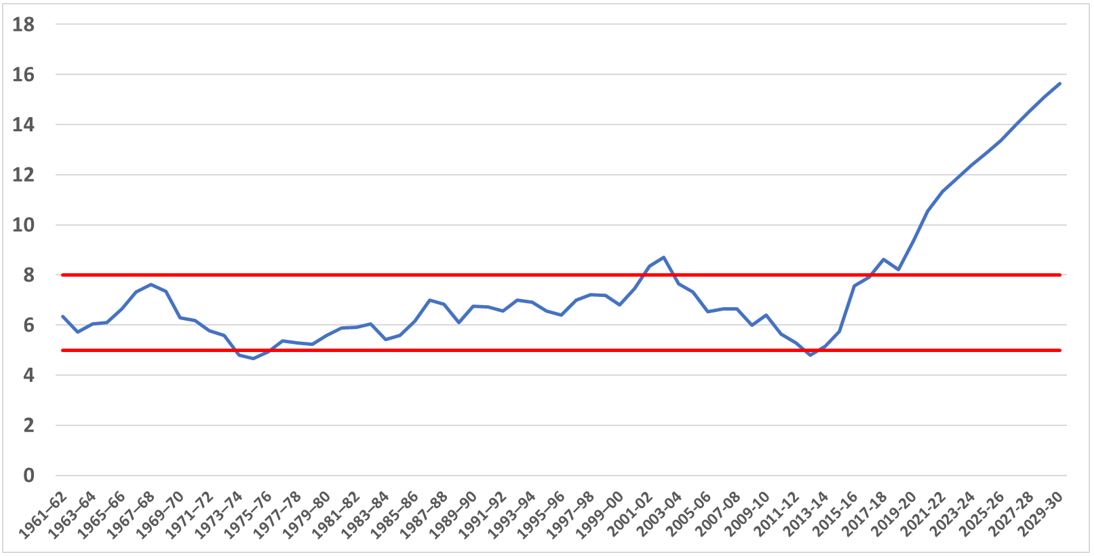

We can combine this information with historical data about spending on both defence and aid to get a view on the relative importance attached to both. The headline finding is that for more than half a century, from the 1960s to the 2010s, the ratio of defence-to-aid spending moved within a pretty narrow band between about 5 and 8. But that ratio is already at a record high (10.5 this year), and is projected to reach 16 by 2030. That’s a relative priority for defence over aid that is simply unprecedented.

Ratio of defence-to-aid spending

Historical defence spending figures are taken from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) from 1961 up to 2001 and from the budget thereafter. Projected defence spending figures are from the recent Defence Budget factsheet which put Australia’s total defence funding at $42.151 billion in 2020-21, $58.175 billion in 2025-26 and $73.687 billion in 2029-30. Spending in the intervening years was projected from these numbers assuming a linear trend (the figure in the same document shows a roughly-linear trend in spending).

Historical aid data is from Devpol’s Australian Aid Tracker. In line with the 2019-20 budget forward estimates, aid spending is assumed to be $4 billion in 2020-21 and 2021-22 before rising to $4.1 billion in 2022-23, and thereafter growing with inflation.

The result is the ratio above. We can also compare aid and defence spending in real terms, and as percentages of the economy. (Traditionally, aid is measured as a percentage of GNI, and defence as a percentage of GDP. We maintain that convention here. The two aggregates don’t differ by more than 5%, and are assumed to grow at the same rate in the future.) Historical inflation and GDP and GNI data come from the ABS. Projected inflation rates come from the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) in its May 2020 economic outlook for 2019-20, 2020-21 and 2021-22. The inflation rates for the rest of the decade are assumed to remain constant at 2% per annum, in line with projections provided in the 2019-20 budget. GDP (and, by assumption, GNI) growth forecasts are from the RBA’s economic outlook, with the 2019-20, 2020-21 and 2021-22 rates forecasted to be -1%, -3% and 6%, respectively. Beyond 2022, GDP and GNI are assumed to grow at a nominal rate of 4.5%, again in line with the 2019-20 budget.

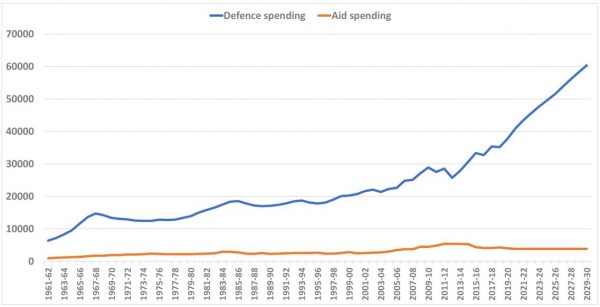

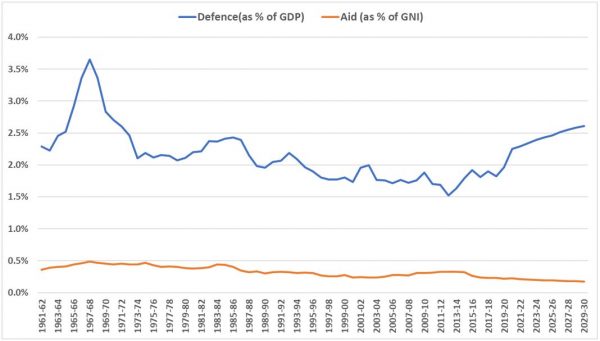

The next two figures compare aid and defence in real terms (in 2019-20 prices), and as percentages of GDP.

Defence versus aid spending (in 2019-20 $million)

Defence spending as % of GDP and aid spending as % of GNI

Australia’s defence spending averaged 2.5% of GDP from the early 1960s to the mid-1980s. With the ending of the Cold War, we secured a peace dividend, with defence spending for the next couple of decades falling below 2% of GDP. Many people think there is now a commitment to spend 2% of GDP on defence, but the government has in fact gone well beyond this. Defence is already 2% of GDP, and by 2030 it will be 2.6%. That will be its highest level since 1971. Aid meanwhile will continue on its sorry downward path as a percentage of GDP, and will reach 0.17% of GDP by 2030, exactly half of its 1960-2020 average.

There have been four reactions to the unveiling of the 2030 defence figures. The massively increased amounts envisaged have, not surprisingly, been welcomed by the likes of the defence-funded ASPI.

Others want us to spend still more. Hugh White has argued that we should be spending 3.5% to 4% of GDP on defence, a share he says we spent in the 1950s and 1960s. In fact, according to the ABS, the average for the 1950s was 3.5%, and for the 1960s, based on the data above, 2.8%.

A third group argues that the government has an unbalanced approach, and that, even from a national security perspective, we’d be better off investing more in aid and diplomacy and less in defence. The problem with that argument, made eloquently recently by Richard Moore, is that our national security strategy is aimed squarely at deterring China, and it isn’t clear how aid and diplomacy will contribute to that goal.

A fourth position is that the massive increase in defence spending is a colossal waste of money, given the lack of evidence that China or any other country is or is likely to become a threat to Australia. From this perspective, much of the $70-plus billion a year we are planning to spend on defence could be spent far better, whether on foreign aid or domestically.

Whichever one of the four positions you take, there is no doubt we have entered into unchartered territory: no Australian government in the last sixty years has ever before given defence such priority relative to foreign aid.

All data available here. Many thanks to Sherman Surandiran for putting the data together.

Australia’s foreign policy in the Pacific in the last few years has been, as Richard Moore puts it, “complacency and under-reaction, followed by overreaction”. The intervention in the Pacific is pretty much following the footsteps of China. Where China goes, Australia follows, from electricity to internet. And on the military front, where US points, Australia goes, from naval bases to increased military budget.

It’s becoming clear to Pacific islanders what Australia’s response will be if China ever decides to reduce its engagement in the Pacific. Logically, Australia will be less interested in intervening in areas that matter: infrastructure. So to keep Australia interested in sectors that Pacific governments think are important, they’ll continue to court China.

It would benefit Australia and the region to think long term, and stop being reactionary.