China giving aid to the Pacific isn’t new, but in recent years ‘China the aid donor’ has become an unavoidable presence. In response, the Australian government is increasing the Pacific focus of its aid. It has also established a lending facility to fund infrastructure work. China is changing the way Australia’s political elites are thinking about aid.

What about the average Australian though? Does their thinking change if they’re told about Chinese aid in the Pacific? Do they think Australian aid should increase in response? Do they think Australia should focus more on the Pacific? Do they think Australia should change the values underpinning its giving?

We sought to answer these questions in a recent research collaboration. Because media commentary about China ranges from sober analysis to alarmist hyperbole, we also sought to learn whether spin designed to make Chinese aid seem as threatening as possible was more effective in changing views about aid than measured analysis.

To answer our research questions, we conducted an experiment involving a public opinion survey run on a broadly representative sample of just over 2,000 Australians, in which participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups:

- A “sober analysis” group that received a short article on Chinese aid in the Pacific. This article was balanced and factually accurate, and similar to a newspaper piece.

- A “alarmism” group that received a similar article. This article was still factually accurate but facts and opinion were spun to make China’s Pacific aid appear particularly threatening.

- A control group that received no article and no information on China.

Participants in each of the groups were subsequently asked whether:

- Australia gives too much or too little foreign aid in total.

- Australia focuses enough of its aid on the Pacific.

- Australian aid should primarily advance Australia’s economic and geostrategic interests, or primarily help people in developing countries.

You can read the newspaper articles and questions here.

The logic of our experiment was the same as that of randomised control trials used in medicine. Because the survey sample was large and people were randomly allocated to the different groups (control, sober analysis and alarmism) the types of people in our groups were more or less identical. Because the groups were effectively identical, any overall differences in responses between groups will have almost certainly have been caused by the articles, and the information they imparted about Chinese aid.

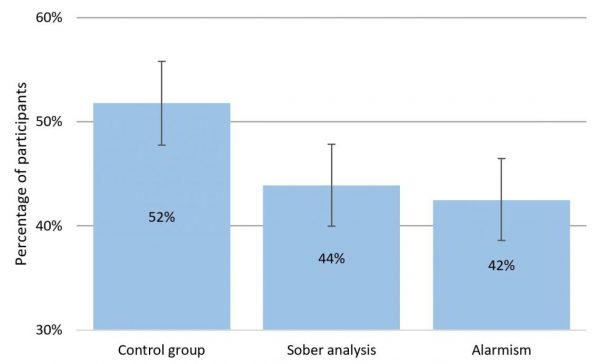

We found that both articles caused a substantial fall in the percentage of respondents who thought Australia gives too much aid. You can see the change in the first figure below. (The changes were also statistically significant; p-values for the effects of both articles were <0.01.)

Percentage who thought Australia gives too much aid

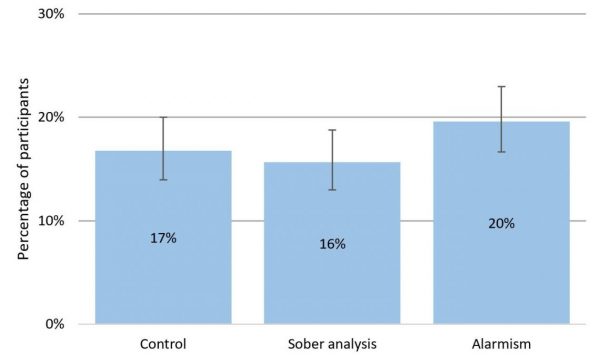

The impact of the China treatments was not symmetrical though. Although the articles reduced the percentage who thought Australia gave too much aid, as the next chart shows, the impact on the belief that Australia give too little aid was much less – only a few percentage points, and neither of the articles produced differences that were statistically significantly different from the control.

Percentage who thought Australia gives too little aid

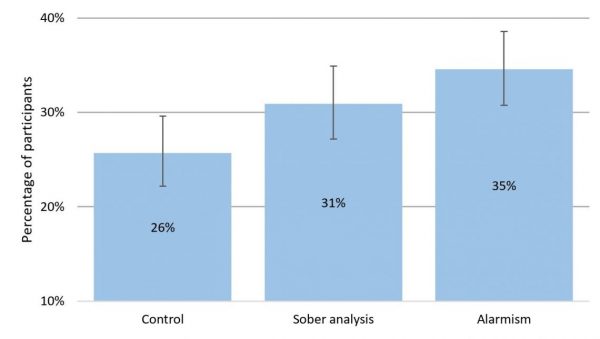

Even though participants were reluctant to say the Australian aid budget is too small, both of our articles changed views about aid to the Pacific. You can see this in the next chart. When told about Chinese aid, more Australians thought a larger share of Australian aid should be focused on the Pacific. The effect of the alarmist article was clearly statistically significant (p<0.01). The effect of the sober article was not quite statistically significant but was close.

Percentage who thought Australia should focus more of its aid on the Pacific

Informing Australians about China’s presence as an aid donor in the Pacific makes them less likely to want aid cut, and more inclined to favour an increased aid focus on the Pacific. That makes sense.

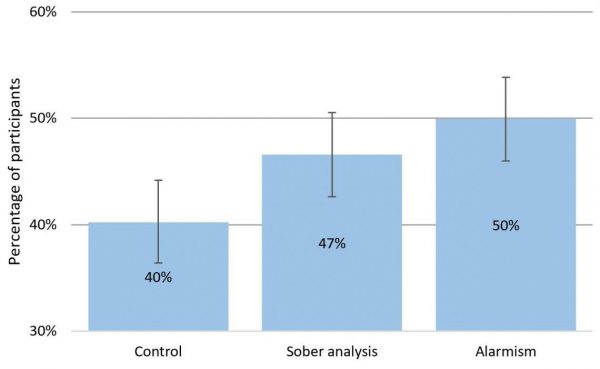

We didn’t expect the next finding though. We thought telling Australians about China in the Pacific would make them more likely to want Australian aid focused on advancing Australia’s interests. The opposite was the case. When we asked whether Australian aid should be spent, “primarily for the purpose of helping people in poor countries”, or “primarily to help advance Australian interests”, both the sober and alarmist articles increased the share of survey participants who wanted Australian aid focused foremost on helping people in developing countries. They also decreased the share of participants who wanted Australian aid focused on advancing Australia’s interests. (Both articles’ effects were statistically significant with p-values <0.05.)

Percentage wanting Australian aid focused foremost on helping people in developing countries

Surely, if Australians were concerned about a rising China exerting geostrategic influence through its aid to the Pacific, they would want Australia to become more hardnosed in its own giving, and more focused on taking care of itself? That’s not what our experiment shows. We think the most likely explanation for this counterintuitive finding is that the average Australian sees the real threat from Chinese aid being to the people of the Pacific, rather than to Australia itself. We can’t be sure, but if that is how the average Australian is thinking, they’re actually being quite reasonable. Aid matters to the small island states of the Pacific, and if Chinese aid is poorly conceived it could cause harm. On the other hand, there’s no evidence yet that aid will buy China real geostrategic influence in a region where political elites are well-practiced at adroitly ignoring donors’ demands. It also isn’t clear how much threat marginally more Chinese influence in a very large sea would actually pose to Australia.

The final surprise in our findings was that, although the alarmist article almost always had a larger effect than the sober analysis, the difference between the two articles was never, itself, statistically significant. (In layperson’s terms, this suggests the alarmist article might have been more effective, but we don’t have definitive evidence.) Perhaps this was simply because the alarmist wasn’t alarming enough. On the other hand, it may have been because the average Australian doesn’t always need to be frightened into changing their views. Sometimes the facts are enough.

A version of this blog first appeared on the Lowy Institute’s The Interpreter here.

Thanks Amanda. I agree, the session at the PNG update was excellent.

Thank you for this very interesting and clearly written blog post.

As was emphasised at the PNG Update conference held at UPNG last week in a session chaired by Professor Stephen Howes and featuring several speakers including Mr Chris Hoy, randomised control trials are very valuable. It is great to learn here of another example of how this method can be applied in the Pacific.

Thanks again,

Amanda 🙂

Hello Amanda, thanks for your interest in this study and the use of randomized control trials in the Pacific. As you mentioned, at the PNG update there were three presentations about RCTs in PNG. The presentations are available here: https://devpolicy.crawford.anu.edu.au/png-and-pacific-updates/png-update