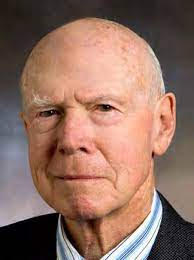

This is an edited version of an address given at the Jim Ingram Memorial held at the Australian National University on 9 August 2023.

We are pretty good in Australia at celebrating our sporting heroes. Our most senior local politicians – and occasionally even public servants – also usually get the kind of attention they deserve when they pass life’s final check-out. But all too often Australians who have made quite brilliant public service contributions to international organisations that really matter remain far less well-known and honoured here than they should be. That has rather been the case until now with Jim Ingram, who died in February this year just a few days short of his 95th birthday.

I am delighted that the ANU, on the initiative of Shiro Armstrong and his colleagues at the Crawford School, have given us today this opportunity to celebrate, with the participation and presence of his son Phil and daughters Catherine and Veronique, his wonderful life and legacy. And I am particularly delighted, as are we all, that Cindy McCain, the current Executive Director of the World Food Programme (WFP), has been so graciously able and willing to join us in doing so.

Jim began his stellar diplomatic career in 1946, at the ripe old age of 18 when he was the youngest cadet ever selected by the then Department of External Affairs. His Australian diplomatic career over the next 36 years culminated in his appointment as head of the Australian Development Assistance Bureau from 1975 until 1982, with postings along the way in Tel Aviv, Washington, Jakarta and New York, and as Ambassador to the Philippines and High Commissioner to Canada. To all roles, Dennis Blight tells us in his excellent obituary, he brought, along with a well-earned reputation for total competence, his trademark healthy scepticism.

But the real peak of Jim Ingram’s professional career came with his appointment in 1982 as Executive Director of the WFP, a position which he held for a decade, until 1992, with the personal rank of UN Under-Secretary General, still the only Australian to have headed a UN organisation at that level.

The WFP is now not only the world’s biggest humanitarian agency but one of its most respected and effective. That it became so is very much the legacy of Jim Ingram – and that’s not just a judgement born of Antipodean bias, but one widely shared internationally, as I know from a number of direct conversations around the world when I was Foreign Minister and head of the International Crisis Group.

Jim’s time at the WFP was, to put it gently, not without its challenges. It has always been, in a sense, the mission of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) to do the WFP out of a job. It’s defensible to the extent that its mission is to create, through technical advances, a global food supply so abundant and well distributed as to make the role of a dedicated food aid and relief organisation redundant. But reality has conspired, in Jim Ingram’s time and since, and no doubt unhappily will continue into the future, to make the role of an independent, highly professional and well-funded global emergency food assistance agency not only necessary, but desperately necessary.

That necessity was not accepted by the FAO in the early 1980s, and Jim Ingram’s huge contribution – told in his wonderfully caustic memoir, Bread and Stones, published in 2007 – was to secure the emergence of the WFP from being a demoralised dependency of the FAO into a fully-fledged, and hugely effective, international agency in its own right. The then FAO Director, Edouard Saouma, was a larger-than-life character determined to concede not an ounce of his hitherto absolute authority to anyone, whatever the rational merits of the case might be. And he was certainly not prepared to give in to an Australian diplomat who had ideas of his own as to how a global humanitarian mission should be run, and whose tenacity Saouma grossly underestimated.

Jim’s blow-by-blow account of the legal, financial, administrative, procedural and political – always political – manoeuvres by which Saouma’s campaign was conducted makes, as I say in my foreword to his book, absorbing reading. Albeit with one’s enjoyment of the spectacle, in all its excruciating pettiness, tempered by remembering how high the stakes were for the hundreds of thousands of men, women and children who depended each year of that battle, and who depend still now, on the WFP’s effective performance.

Jim’s side of the argument, presented with as much academic detachment as one could reasonably expect from a direct antagonist, has unquestionably prevailed in the judgement both of his contemporaries, and of history. That it has is testament to his competence, leadership abilities and perseverance. It is also testament to another factor all too rare in public life: Jim’s willingness to take his personal interests out of the equation, announcing that he would seek no further public office when his reform task was done. Would that many more followed his lead.

Bread and Stones is much more than the tale of a bureaucratic cage-fight, though it ranks as a classic in that genre. It is a superb analysis of the shortcomings of the UN system and international organisations – all too many of which unhappily persist in too many places (if not in the WFP) today – and what is needed to overcome them. The kind of leadership skills required; the processes by which leaders should be elected or selected; the kind of member state oversight required; and the kind of mindset changes needed to shift member states away from focusing entirely on national interests narrowly conceived. It covers much more on what is best for the international community as a whole: getting them to resist playing within the UN system a brand of politics that most (if not all, in this Trumpian age) would be embarrassed to be caught out playing at home.

Jim Ingram practised what he preached about leadership within the UN system. If reform was to happen, it was chief executives, as he put it, who had to drive it. They should be competent and brave enough to break through, as need required, the culture of circumspection, mutual accommodation and tolerance of poor performance that all too often prevails throughout the UN family; and, if they acquired real power, to exercise it well.

In his retirement years, Jim honoured his commitment to seek no further public office but maintained a lively interest in international development and in Australian foreign policy. He was active in the Australian Institute of International Affairs of which he was a Fellow, the Crawford Fund of which he became patron, and the ANU’s Asia-Pacific College of Diplomacy. He also established the Ingram Fund for International Development in Law as a permanent endowment for the University of New South Wales.

I didn’t know Jim as well, or see as much of him over the years, as I would have liked to, but I found in my dealings with him, we were very much kindred spirits, maybe because his temperament was not unlike what I once described mine to be: “not of the cloth from which zen masters are cut”. He had a razor-sharp, questioning and sceptical mind, and an unquestionable commitment to integrity and decency in public policy and administration, with an ability to distinguish at forty paces the difference between the good, the bad and the questionable in both. He was a lively and engaging conversationalist, and a thoroughly decent human being.

James Charles Ingram AO deserves an honoured place in the pantheon of great Australian internationalists, and I hope and expect – not least for the sake of his surviving family, to whom my condolences – that today’s celebration of his life and career will give him a little more of the recognition and respect he so obviously deserves.