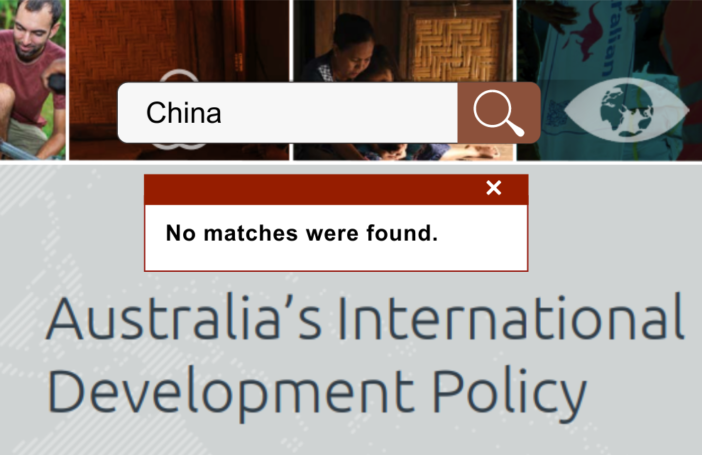

The government has, after several months of speculation, now released its new international development policy. Threats, both named (economic uncertainty, climate change) and unnamed (China), loom large. Notwithstanding the ongoing focus on the pursuit of Australia’s wider geopolitical objectives, the policy has been broadly welcomed by the sector. Indeed, “statecraft” is a term that some leaders in the sector have now embraced. So, perhaps expect to see more Richelieu and Kissinger and less Acemoglu and Sachs on Australian aid advocates’ bookshelves.

Reprising a previous blog, it is worth looking at the new policy across three dimensions: purpose, priorities and “plumbing”. In terms of purpose, the government has largely adopted the objective from the Coalition’s 2020 interim aid strategy, Partnerships for Recovery. Contributing to a “stable, prosperous and resilient Indo-Pacific” has been adjusted to “The objective of Australia’s development program is to advance an Indo-Pacific that is peaceful, stable, and prosperous.” Not many would argue with the aspiration. But the absence of any mention of poverty reduction in the objective, as articulated in the policy’s original terms of reference, was notable. To the relief of some, this has been subsequently appended to the end of the objective which now acknowledges that “To achieve this [objective] requires sustainable development and lifting people out of poverty.”

There is no reference in the objective or indeed anywhere else in the document to the moral case for aid. This is notable given several speeches from the Minister for International Development and the Pacific, Pat Conroy, that have articulated the importance of this rationale. For example, speaking in September last year, the Minister declared:

I’m convinced that the moral argument is the most compelling of the cases for foreign aid. Tackling poverty must be an urgent imperative for all people of conscience, especially for a generous nation committed to the fair go.

The first of the five chapters of the new strategy is titled “A development program that reflects who we are”. It talks at length about Australia’s own democratic credentials, commitment to human rights, multiculturalism and our First Nations heritage. Conspicuous by its absence is any reference to Australia being a “generous nation”. Perhaps that is because when we think about aid from a moral perspective, as most do, we emphasise people, their needs and their wellbeing. Instead, the rationale for aid presented in the policy is framed predominantly in terms of “states”, “interests” and “regional stability”. These are big, impersonal and abstract concepts that, while shoring up an elite policy consensus, may not contribute to a broadening or deepening of the public constituency for aid.

On priorities, the government nominates effective and accountable states, state and community resilience, connecting partners with Australia and regional architecture, and collective action on global problems “that affect us and our region” as the four key focus areas. Putting aside debates about whether aid can actually help build effective and accountable states, the omission of economic growth from this list is somewhat unexpected. While there are also debates about the relationship between aid and growth, economic growth is viewed by most development experts as a necessary, if not sufficient condition, for sustainable development and poverty reduction. And a growth objective would have captured both the national interest and the development rationales behind programs like Pacific labour mobility, trade and education more readily than a concept as abstract as “regional architecture”.

The government’s ability to dedicate additional resources to its two flagship sectoral priorities – gender equality and climate change – has been constrained by its decision to keep the aid budget flat, in real terms, until 2036-37. In response, it has adopted an approach pioneered by Julie Bishop during the Coalition’s lean aid years – that is, earmarking a proportion of existing aid for priority areas through sector targets. In Bishop’s case the priority was aid-for-trade, where a 20% spending target was applied as part of the Abbott government’s 2014 aid policy. (In this era, the lens wasn’t “statecraft” but “economic diplomacy”.)

For its part, the Albanese government has decided that all new programs over $3 million will need to have a gender equality objective; effectively a 100% target for aid programs of this size over the next ten years or so. According to the latest OECD data, in 2021 the proportion of projects with a principal or significant gender equality objective was 41%.

On climate change, the government has committed to 50% of all new bilateral and regional investments valued at over $3 million having a climate change objective by 2024-25, rising to 80% by 2028-29. According to DFAT, the current proportion is around 25%. Transparency about what is counted towards this commitment, and why, will be critical given ongoing and legitimate concerns about what donors, including Australia, classify as “climate aid”. Improved transparency will also be required in relation to the gender commitment.

It is not clear whether this earmarking approach will withstand the reality of the “polycrisis” unfolding around us. Ultimately, more aid-for-trade under Bishop meant less for health. What will be the potential costs of more aid for climate change? If we really think, as the strategy states, that our region is facing multiple and compounding challenges, then we should be increasing aid rather than pretending we can do more within a flatlining aid budget.

The part of the new policy that encompasses the biggest set of new commitments relates to “plumbing” – aid planning, performance, accountability and transparency. New measures to strengthen country and regional strategies, investment monitoring and evaluation, direct engagement with local partners, and public performance reporting and aid data accessibility are some of the most substantive elements of the policy. The measures demonstrate an ongoing, if incomplete, acknowledgement by the government that these systems and functions have been severely degraded in the ten years since the integration of AusAID and DFAT.

As others have noted, consistent resourcing, senior leadership and effective oversight – including strengthening the independent elements of this oversight – of these new commitments will be key to ensuring that these reforms survive the short-term pressures and incentives that will inevitably draw attention away from their implementation.

Ultimately, if our systems can’t demonstrate that we are helping deliver real impact for people and communities then Australia’s claims about being a “partner of choice” will ring hollow. I’m no student of Kissinger, but I’m pretty sure that wouldn’t be good for statecraft.

All blogs on the 2023 Australian international development policy can be found here.

Thanks again, Cameron

I read that “Factsheet” with a great deal of interest and note it made no reference to any existing and annual responsibilities for reporting the Department’s “performance” under the PGPA Act, where Section 39 specifies:

“39 Annual performance statements for Commonwealth entities

(1) The accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity must:

(a) prepare annual performance statements for the entity as soon as practicable after the end of each reporting period for the entity; and

(b) include a copy of the annual performance statements in the entity’s annual report that is tabled in the Parliament.

Note: See section 46 for the annual report.

(2) The annual performance statements must:

(a) provide information about the entity’s performance in achieving its purposes; and

(b) comply with any requirements prescribed by the rules.”

I could only find them using this search key https://www.dfat.gov.au/search?keys=PGPA+Performance+reports,

where it was possible to find examples, such as

* Technical Disaster Risk Reduction Program in PNG Evaluation Report and

* Mid-Term Review Report of the Pacific Insurance and Climate Adaptation Programme (PICAP) and on the last page is

* Achieving the millennium development goals: Australia’s support 2000-2010

These have now been required for 10 years, since the PGPA Act was introduced in 2013, yet not publicised.

Thanks Cameron. It is quite encouraging to see in the new International Development Policy at least 7 nicely phrased references to “monitoring”; 17 references to “learning”;and 18 references to “evaluation”. There are also several references to “enhanced accountability and transparency”. Good. However, you can’t help but wonder how much traction that will get in practice when there is still no longer an independent office of development effectiveness, or any clear reference to re-establishing one in the new policy. And I wonder if our standing and credibility as a “partner of choice” would have been strengthened further among partner countries, and with partner UN and other organisations, had the new policy committed to having a genuinely independent office of development effectiveness, together with the tracking of the extent to which lessons were subsequently learned. Or not.

Thanks, Ian.

I agree that if the government is not going to re-establish ODE/IEC (it is still not clear why they are not doing this given Labor’s strong criticisms at the time) then it should, at the very least, increase the number independent members of its Development Program Committee and appoint a senior evaluation officer who reports directly to this committee. Several submissions recommended the latter.

DFAT have produced this factsheet which compares pre-aid policy arrangements with the new commitments: https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/monitoring-evaluating-development-factsheet.pdf

Thanks again Cameron – quite a reflective article, especially on establishing the real impacts and “effectiveness” of our aid. Eventually. Though DFAT is like all APS Departments, required to produce an Annual Performance Report under the PGPA Act.

I am aware that DFAT has a “Development Effectiveness Division” https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/dfat-org-chart-executive.pdf. But that means its activities are very much subject to the alternative priorities and decisions of senior DFAT management. At any time. The evaluation functions do not sit to the side of the Department and be able to operate independently.

Fortunately DFAT and the entire APS is now being subject to demonstrating the effectiveness of their programs, through the Australian Centre for Evaluation being established in Treasury – https://ministers.treasury.gov.au/ministers/andrew-leigh-2022/media-releases/australian-centre-evaluation-measure-what-works

Thanks, Peter.

DFAT has stated that it will “work closely with the recently established Australian Centre for Evaluation to further ensure the rigour of our evaluation practice.”

https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/monitoring-evaluating-development-factsheet.pdf

This will be something to watch. But I suspect the Centre’s capacity will be stretched across larger govt programs and it’s ability to engage on DFAT programs will be constrained.