Galileo is famously quoted to have said, “Measure what can be measured, and make measurable what cannot be measured.”

In a move that would presumably have pleased Galileo, in 2018 the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC) established a policy marker – a tag that can be attached to aid activities when related financial flows are reported to the OECD by donors – on the inclusion and empowerment of persons with disabilities. The marker provides a mechanism for monitoring and reporting project-level data on the degree to which DAC members’ development assistance has disability inclusion objectives.

While far from perfect, the marker provides an important mechanism to support reporting, accountability and transparency around Australia’s development efforts on disability equity.

CBM Australia recently explored Australia’s performance against the marker, how it adds value to our existing reporting system, and the opportunities at hand to extend use of the marker as part of the forthcoming international disability equity and rights strategy.

How does Australia perform? In 2021, 18% of Australia’s bilateral official development assistance (ODA) was identified as disability inclusive – that is, having a marker score of 1, significant objective, or 2, principal objective. However, out of a total of 569 reported disability inclusion projects, only 12 had disability inclusion as their principal aim.

When looking at DFAT’s own expenditure tracking tools, it’s worth noting that the practice of providing an annual estimate of the amount of ODA that “provides some level of assistance to disabled persons” is both longstanding and methodologically advanced by comparison with the efforts of other development actors. Notwithstanding this, the percentage of Australia’s overall development assistance within this category remains low – at 2.5% in 2021-22 – and the value of that assistance has reduced dramatically over the last decade, down almost 40% from its peak in 2010-11 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: ODA providing “some level of assistance to disabled persons”, 2005-06 to 2021-22, in real terms

From Re-establishing DFAT’s leadership on disability equity and rights, page 8.

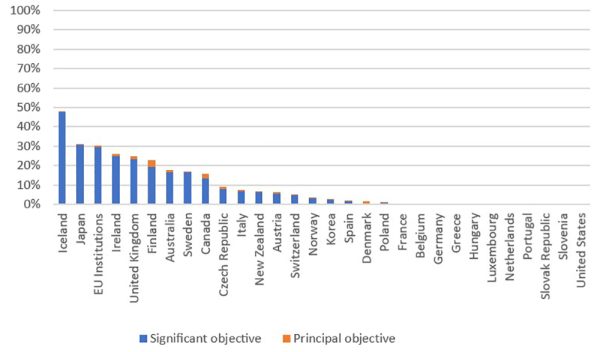

On the question of added value, we found that the marker complements Australia’s own expenditure tracking in ways that are relevant and desirable in the context of our commitment to international disability equity. Importantly, the marker allows for international comparisons to be made (Figure 2). While caution must be exercised in making these comparisons, the marker gives a valuable indication of DAC members’ ambitions on disability inclusion at the point of investment. In addition, the DAC’s marker-based data is available in more granular detail than DFAT’s, providing transparency that is critical for the accountability work of development stakeholders, including organisations of people with disabilities.

Figure 2: Percentage of bilateral ODA reported as disability inclusive by DAC members in 2021

From Re-establishing DFAT’s leadership on disability equity and rights, page 7.

In fact, as DFAT develops a strategy to guide disability equity programming over the coming 5-10 years, and given Australia’s recently strengthened commitment to deepening accountability and enhancing transparency across the development program, there are a number of important opportunities to harness the marker in support of development objectives. There exist both immediate opportunities and more ambitious and innovative opportunities.

In the short term, DFAT could take the following steps:

- further improve the quality of data being reported against the marker, possibly drawing on good practices utilised in other contexts

- increase the visibility of reporting against the marker, which could be done by fully integrating the marker, along with DFAT’s existing reporting tools, into resources such as the forthcoming online data portal

- explore ways in which to improve the tracking of spending on the intersection of disability and other characteristics

- build on efforts already underway to increase efficiency and cross-fertilisation between the marker and DFAT’s own reporting mechanisms.

At the same time, of course, we would also hope to see the government increase the volume of funding with disability equity as an objective, as outlined in a joint call from the development sector.

Beyond the above steps, we identified a small number of more ambitious and innovative opportunities DFAT might take in relation to the marker. These include developing tools to inquire into the extent to which programs work within existing inequalities or seek more disruptive, transformative change; and exploring ways to have more precise estimates of the level of spending contributing directly to disability equity, for example through tagging at the individual item level.

In the context of the new international development strategy’s emphasis on equity and rights, these options are well worth considering.

One of Australia’s major strengths as a development actor is our intentional approach to advocacy and leadership in international forums. It is undoubtedly true that Australia’s leadership on disability inclusive development has led to important positive outcomes, including increasing the capacity of and space for organisations of people with disabilities, and supporting the development and utilisation of tools to collect disability inclusive data.

DFAT has an opportunity to extend this important work to the DAC marker by playing a strong and proactive advocacy role in the following areas:

- expanding utilisation of the marker by making it mandatory, as is the case for most other policy markers, and encouraging multilateral organisations to report against the marker

- strengthening the design of the disability marker itself, for example by introducing a minimum requirement that all projects “do no harm”, as for the gender equality marker.

As it develops the new disability equity and rights strategy, DFAT must grapple with how to ensure development efforts respond to the needs and priorities of people with disabilities, and support them to have the agency that is an essential element of equity.

The DAC disability marker is an important tool supporting delivery on Australia’s commitments, driving collective global effort, and enabling people with disabilities and their representative organisations to hold the government accountable for delivery against those commitments.

Read more about the DAC disability marker and Australia’s engagement with it in CBM Australia’s briefing paper.

Disclosure

CBM Australia receives grants under the Australian NGO Cooperation Program. CBM’s Inclusion Advisory Group has also been DFAT’s technical partner on disability inclusion since 2010 under partnership agreements.

Leave a Comment