Coinciding with the adoption of the Busan principles at the international level in 2011, the recent opening up of Myanmar, the newest donors’ darling in Asia, has created dilemmas for donors wanting to help that country transition out of fragility. In particular, as I will argue in this two-part post, the outcomes of the Myanmar peace process and difficulties in resolving a longstanding and deeply entrenched conflict have highlighted some important limitations of the Busan principles.

The New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States

Following the first High Level Forums in Rome in 2003, in Paris in 2005 and in Accra in 2008, the Fourth High Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness (HLF-4) held in Busan (South Korea) in 2011, determined the international standards on good development and aid effectiveness that all development actors ought to endorse. These standards revolve around four principles:

- country ownership of development strategies and priorities;

- a focus on results that should enable the eradication of poverty and reduction of inequality;

- inclusive partnerships that promote trust among development actors;

- transparency and accountability among development actors and between them and the government.

For the first time, the issue of conflict and fragility took center stage in Busan, and a “New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States” (the New Deal) was endorsed by 41 countries and international organizations, thus highlighting endeavors of the international community to develop a different development paradigm in challenging contexts and to guarantee that development programs in fragile states are more appropriately and effectively managed. The New Deal focuses on five main goals: legitimate politics; justice for all; security for all; economic foundations (employment for all); revenues and services for all.

The most significant principles of the New Deal revolve around the need to work on capacity-building when engaging in a conflict-affected country, and more generally, to reinforce the resort to “national systems”. In other words, national institutions and actors must be given the autonomy to conduct their transitions out of conflict and/or fragility and international donors should commit to work and channel aid through these national systems to assist countries establishing their own capable and legitimate institutions, with the objective of avoiding prolonged assistance dependency.

Myanmar: ideal terrain for the application of the Busan principles?

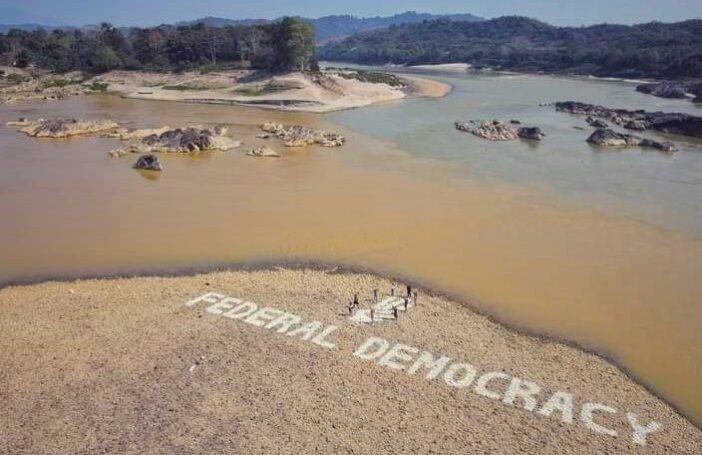

Myanmar has recently opened-up following 50 years of authoritarian military rule. The Government of Myanmar, headed by President U Thein Sein, has embarked upon a significant process of reform since 2011, aimed at addressing crucial economic and social challenges as well as long-lasting conflicts with ethnic minorities in the country’s borderland regions. The Republic of the Union of Myanmar is thus undergoing a multifaceted transition that is unfolding on several fronts:

- finding a way to sustainably end more than half a century of armed conflict;

- ensuring a democratic system surfaces, as epitomized by the 2015 elections after years of repression and dictatorship;

- re-weaving the social fabric after an era of profound mistrust between state and society;

- reinvigorating the economy after decades of isolation.

This largest and undoubtedly most tangible transition in the country’s recent history has triggered the lifting of international sanctions and a rush of aid donors.

Nearly coinciding with the adoption of the New Deal at the international level, the donor community’s newly found emphasis on Myanmar has seen the country cast as a natural place to apply the newly agreed measures and principles. Yet, despite significant progress on the political, social and economic fronts, the country remains stricken by poverty and decades of civil wars in border areas, which have given rise to thousands of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) and refugees. Unsurprisingly, the country ranks 24 out of 178 (Alert Category) in the Fund for Peace Fragile States Index 2014.

Against this backdrop, there is a crucial need to assess whether New Deal undertakings and commitments to Fragile States Principles (FSPs) are informed by the complexities of establishing a sustainable peace in parallel with addressing the issue of poverty in the context of an elite-driven transition.

The New Deal’s limitations, as demonstrated by the case of Myanmar

What is actually emerging from the most recent outcomes of the Myanmar peace process is that the Busan principles appear not only insufficient to address the question of fragility in the country but also that, if not dealt with appropriately, they could be detrimental to the general direction of the peace process in Myanmar.

First of all, the idea of the need to guarantee the country “ownership of development”, which has become a topos in the development world, seems to ignore some crucial realities pertaining to the experience of the transition in Myanmar. Favoring governmental channels in contexts of widespread mistrust between the state and the society can indeed not only appear counter-productive if the constituents do not buy into the projects implemented by the government, but can also create a discrepancy between the beneficiaries of aid programs that share the interests of the government and left-aside stakeholders with potentially antagonistic visions or conflicting interests.

In the case of Myanmar, even though the army has officially ceded power to a civilian government, the military background of a range of officials and the domination of the military-backed party in the parliament (Pyidaungsu Hluttaw) tarnish the image of the current administration, which still tends to lack popular legitimacy. This is evidenced in the peace process, whereby some moves made by the current administration have sometimes been interpreted by ethnic nationalities as mere calculations to advance its own interests rather than genuine steps towards national reconciliation.

Second, and more importantly, it is worthwhile to recall that the government in Myanmar is both a development partner and a party to various conflicts. Indeed, on the one hand, the government signed the Nay Pyi Taw Accord [pdf] in 2011, aiming to strengthen cooperation with global partners and ensure better public service delivery. But on the other hand, it is still involved in various conflicts, as recently evidenced in the tensions around the Letpadaung Copper Mine projects in Sagaing Division (underlining the conflict between the government and several civil society groups) and recent clashes between government troops (Tatmadaw) and the Kokang rebels in Shan State.

This dual role is highly problematic since it carries with it the potential that official efforts to promote state-building, nation-building development and peace-building will give rise to conflict and trigger tensions with antagonistic stakeholders and/or other parties to the conflict. Crucially, this highlights the risk that the donor community’s requirement to work with Myanmar authorities in particular, or with any official institution in a transitional country in general, often praised under the mantra of “supporting the reformers”, may trigger an amalgamation of the development and political objectives of governing bodies.

In the second part of this post, I will illustrate the point above with some examples.

Mathilde Tréguier is working in Myanmar on peace issues and questions related to inter-communal violence. She graduated in 2014 from the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) with an MSc in International Relations. She also holds an MSc in Management from the EMLyon Business School.