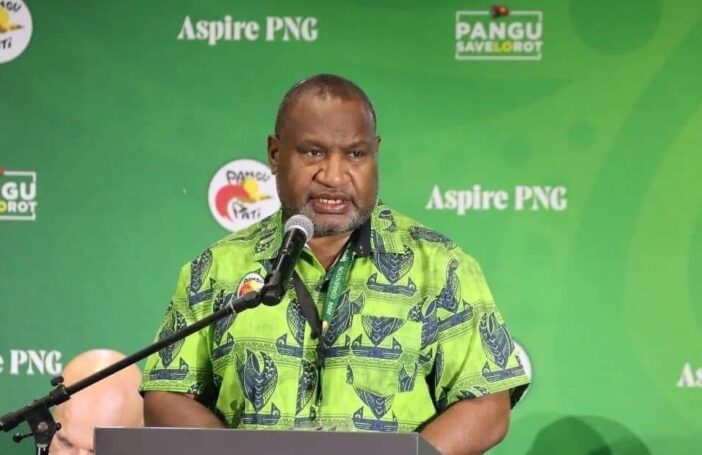

Papua New Guinea’s Prime Minister James Marape launched the country’s current Medium Term Development Plan (MTDP) in July 2023. It is the fourth in the most recent series of five-year plans, though such plans have been a part of PNG’s governance since independence. This one is Marape’s first national development plan since coming to power in 2019 and covers the five years up to the next general election in 2027.

The 330-page MTDP IV is divided into three parts: policy directions; sectoral programs and interventions; and provincial and district information. The report is lavishly illustrated and incredibly detailed (though not always correct, claiming for example on p. 213 that only one language is spoken in Enga, whereas in fact there are three: Enga, Ipili and Hewa). It has an impressive range of targets and interventions, and a strong and welcome focus on agriculture.

The big problem though is that the plan’s economic analysis is far from convincing.

One odd feature is the target to increase exports but decrease imports. The figures are not always consistent but at one point the plan says the target is “to more than double the value of exports to K65.7 billion, and reduce the value of imports by some 25% to K9.5 billion by 2027” (p. 118).

This is a very mercantilist view: exports good, imports bad. In fact, the only value of exports to a country is that they enable the purchase of imports. Increasing exports while decreasing imports means an ever-growing current account surplus, and makes no sense at all. If the 2027 GDP target of K164 billion is achieved, then the current account balance in that year would be about one-third of GDP, which is astronomically high. Import substitution is an important goal but should result in the freeing up of foreign exchange to purchase other much-needed imports, not a total reduction in the import bill. We’re not aware of any country that has developed by reducing its imports.

Equally worrying is the treatment of GDP. The overarching goals of MTDP IV, according to the Prime Minister’s foreword, are “to grow the economy to K200 billion, double both internal and external revenue, and create an additional one million jobs” and to “achieve our dream to be the ‘Richest Black Christian Nation’, and a ‘middle income’ country by 2030”.

Such goals are either unachievable or confusing. Analysis has shown that there is no way PNG can get close to becoming the richest black Christian nation by 2030. And the country is already classified as middle income. (Perhaps the Prime Minister means upper-middle income, but more on that later.)

Rather than targeting GDP, the focus should be on the non-resource sector of the economy which supports the bulk of the country’s population for jobs, incomes and livelihood.

It is also critical to adjust for inflation when measuring the growth of any economy. In fact, no real (that is, inflation-adjusted) growth target can be found in the plan, whether for GDP or non-resource GDP. Actually, there is no discussion of inflation at all. Without knowing what assumptions are being made about inflation, it is impossible to assess the meaning or ambition of a nominal GDP target. If prices double, nominal GDP doubles, but no one is better off.

The target presented for nominal GDP (K164 billion in 2027) implies an average GDP growth rate of 6.8% from 2021 to 2027. Projected annual population growth is an incredibly high 4.8% (p.185) so that is only 2% nominal GDP growth per person. Inflation in PNG will certainly be higher than 2% over the next five years. It therefore looks like the plan is projecting negative real growth in GDP per capita.

Other data provided for nominal GDP per capita (see the notes at the end of this blog) suggest a target average nominal growth of 4.3%, but again that is roughly what one would expect inflation to be. (And these per-capita figures imply population growth of 2.5%, which is sensible but only about half of the 4.8% presented as the plan’s own projected annual population growth.)

Yet another target of MTDP IV is given for GDP per capita in US dollars (USD3,000 in 2027), again not adjusting for inflation. This target implies a nominal annual per-capita growth rate in US dollars of just 2.0% from 2021 levels, which again is likely below US inflation over the next five years. Per-capita income of USD3,000 in 2027 is also inconsistent with the plan’s aspiration for PNG to be an upper-middle income country by 2030 (p. 6), since the threshold to graduate from lower-middle to upper-middle income status is just above USD4,000.

GDP, population and inflation are all difficult to estimate accurately, but the plan needed to be much clearer about what its estimates (or assumptions) for these variables actually are. If, adjusted for inflation, economic growth is lagging population growth, then average living standards are falling, and prosperity is reducing, not increasing. The plan’s pessimistic economic projections are inconsistent with its title, National prosperity through growing the economy. They are particularly hard to understand given that it assumes that three large resource projects come on stream during the next five years (Papua LNG, P’nyang LNG and Wafi-Golpu gold/copper).

A critical aspect of national planning is strong economic analysis. Unfortunately, the economics of MTDP IV is extremely weak indeed.

Data notes regarding GDP growth rates in MTDP IV:

- Nominal GDP is projected to grow from K110 million in 2021 (Executive Summary) to K164 million in 2027 (p. 2), which corresponds to an average nominal GDP growth rate of 6.8%.

- GDP per capita is projected to grow from K9,337 in 2021 (Executive Summary) to K12,000 in 2027 (p. 2) which corresponds to an average nominal GDP per capita growth rate of 4.3%.

- GDP per capita in US dollars is projected to be USD3,000 in 2027 (page 2). A GDP per capita of K9,337 in 2021 (as per the above bullet point) corresponds to USD2,661 given the PGK/USD 2021 exchange rate of 0.285 (PNG Economic Database), implying annual average GDP per capita growth in US dollars of 2.0%.

MTDP IV does not imply a falling living standards in PNG. The title of the article is, unfortunately, misleading and inaccurate.

Maybe the article should have been titled “Even with unrealistically high population projections, MTDP implies rising living standards”.

On the first measure of living standards, there is now agreement on the nominal GDP growth rate being 8.8% per annum in the Plan.

The Plan does use an unrealistically high population growth figure of 4.8% (more on this later).

The price deflator in converting nominal GDP to real GDP from 2022 to 2027 is 2.5%. This is the official GDP price deflator used by the PNG Government over this period (see more on this below).

This means that on the GDP forecasts, real per capita incomes are increasing by 1.5% per annum (8.8-4.8-2.5). This implies rising living standards.

Using the second measure of GDP per capita growing by 4.3%, with the GDP deflator of 2.5%, there is real growth per capita of 1.8%. This also implies rising living standards.

Using the third measure of GDP per capita in US dollars, the average GDP per capita growth rate is 2.0%. With a price deflator of 2.5%, this does mean a 0.5% fall in GDP per capita in US dollar terms. However, there is then the variable of the exchange rate. Since 2022, the US dollar to the Kina exchange rate has moved some 5%. By itself, this exchange rate movement averaged at 1% per year over five years once again moves the real GDP per capita growth rate in PNG into positive figures in Kina terms.

MTDP IV of course has to build on other Government documents. In the economic section of the report, the Plan is clear that it builds on the Treasury forecasts of GDP. The Plan then increases these forecasts, largely because the Plan is based on the commencement of major resource projects (so a real measure of changes in GDP). Treasury does not include new resource projects based on standard international practice for budgeting of not including resource projects until the Final Investment Decision. However, for Planning documents, there is more latitude.

As the plan is based on the Treasury GDP numbers, then the Treasury GDP figures, with their associated deflators, are the source of PNG’s official figures of taking into account “inflation” (as the NSO does not produce forward year estimates). When talking of inflation, the usual reference is to the Consumer Price Index, and the CPI does drive most price index estimates in the non-resource sector. Indeed, the overall deflator for non-resource GDP from 2022 to 2027 does average 5%.

However, and I should have picked this up in my earlier comments, we are talking about overall nominal GDP, and this also needs to take account of price movements in the resource sector, especially movements in international commodity prices. The most relevant of these for the GDP figures underlying MTDP IV is the projected 28% fall in prices for the oil and gas sector, which in 2022 accounted for 23.7% of GDP. When building this “negative inflation” for the resource sector into the overall “inflation” for GDP – known as the GDP deflator – the GDP deflator index moves from 167.5 in 2022 to 188.7 in 2027. This is a 12.7% increase in prices for GDP as a whole over 5 years – generalised to the 2.5% annual price index referred to above (although the compound rate is lower at 2.4%). All of these figures on price indexes are available in the annual budget documents (2024 Budget, Volume 1, p151). This is a rather boring table setting out all these assumptions – and I have some sympathy for the authors of the Plan not going into so much detail, although fair point that some higher level price figures could have been included.

On the population figure of 4.8%, this number is indeed included in the plan. The figure likely represents the massive uncertainty about PNG’s population estimates, and therefore growth rates from previous years. It was a shock last year to receive the UNFPA report, since adopted by the NSO, of a massive increase in estimated population in 2021 from the 9.1 million in the UPNG/ANU economic database to 11.8 million – nearly 30 per cent. There is now the issue of creating a time series, with annual growth changes, going back to not just the 2011 Census, but also the possibility that these population estimate errors may even go back to the times of Independence. However, the 4.8% figures is just unrealistic. Most commentators, consider the earlier NSO estimate of 3.1% was too high. The current highest population growth rate estimate for any country in the world is 3.7% (Niger) according to World Bank data. 4.8% would have PNG’s population growing at a much, much higher rate than any other country in the world. This is just not realistic, and the headline of an article analysing a 300 page plus plan should not rely so much on just one figure.

Thank you for your comments, Paul. Definitely if the GDP deflator is only 2.4%, then GDP per capita growth in the Plan is positive, even given its high population growth target. This is not something analysts could have been expected to guess. It definitely should have been made explicit within the Plan. Indeed, that is one of our main points – that much greater clarity is needed around the Plan’s economic assumptions.

But we also need to look at non-resource GDP, which we say in the blog should be the focus and which the government has repeatedly said is a much better indicator of living standards than total GDP. Since GDP per capita growth seemed to be negative in the Plan, we assumed the same for non-resource GDP especially given the three big resource projects. However, if GDP per capita growth is positive, we need to double-check what is being projected for non-resource GDP.

Using Table 3.2, which you drew our attention to, annual average nominal non-resource GDP growth in the Plan between 2022 and 2027 is 7.5%. The Treasury deflator for this variable is 4.8% in the 2023 budget, so real non-resource GDP growth is 2.7%. So with the Plan’s population growth target of 4.8%, non-resource GDP per capita growth is negative. We are back with the conclusion that the Plan is projecting negative living standards.

Yes, 4.8% is high as a population growth target, but it is the target in the Plan and we are assessing what it in the Plan. And even with a lower population growth, 2.7% real non-resource GDP growth could well translate into negative per capita GDP growth.

The Plan is more pessimistic than Treasury regarding non-resource GDP, with the former giving nominal average growth over the 2022-2027 period of 7.5% for this variable and the latter 9.8% (2023 budget). This is odd, and too pessimistic. In fact, for the approximately 50% of GDP that excludes resources, agriculture, forestry, fishing and manufacturing the Plan is projecting negative real growth. It is not clear why as one would expect a construction boom with three new projects.

Your additional insights have certainly been helpful and we have a better understanding of the Plan’s projections now. Now said, these new findings do support the original conclusions which is that the Plan is projecting declining living standards and that, more broadly, the economic analysis underpinning the Plan is weak. The numbers should have been scrutinised before and not only after the Plan was published. And, to repeat the other main point made in our blog, the idea in the Plan that aggregate imports should fall makes no sense.

This is actually a fourth set of figures consistent with our theme that the Plan is projecting declining living standards. If 2022 GDP is K107.8 billion and 2027 GDP is K164 billion, then annual average growth is, as you say, 9% (8.8% to be precise). The Plan targets annual average population growth of 4.8% (p.185). This is high, but it is clearly presented in the Plan as the target for population growth. So the implied per capita growth target is 4%, and that is below the expected rate of inflation (not given in the Plan, but as you suggest could be around 5%). We’re not saying the MTDP IV intentionally projected declining average living standards, but that’s what its numbers actually imply.

[Conflict of interest alert – I work for the PNG Government]

Table 3.2 on page 15 of the MTDP IV sets out the specific GDP projections in the plan. These show an increase from an estimated GDP in 2022 of K107bn (the actual outcome was better at K111bn based on latest forecasts) to K164bn in 2027, an increase of 53% over 5 years. The nominal growth rate in GDP is therefore not 6.8% set out in this article, but 9% per annum compounded. Allowing for 5% inflation, and population growth rate of 3.1%, this implies an increase in real GDP per capita of around 1% per annum.

This is not falling standards.

Disappointed by the standards of this analysis – with a focus on the Executive Summary and page 2, not the more detailed analysis provided in the Plan.

There are uncertainties about PNG’s current level of population, and therefore its population growth rate. This year’s population census will hopefully assist with this. At this stage, the above comments are based on the previous NSO estimates of a growth rate of 3.1%. This is still higher than the figures used by the World Bank and others (including previous analysis by the ANU such as the 2.7% rate used in the UPNG/ANU economic database). Lower population growth rates would increase the annual increase in real living standards.

Of course, PNG is looking to lift these real economic growth targets even further.

This is why the Pangu Party policy is targeted at lifting real non-resource GDP growth rates by at least 5% per year. This allows for steady increases in real living standards, and even small annual gains can compound to major advances over decades.

This comment does not address other issues within the MTDP IV. However, the headline of this article is arguably misleading and therefore the focus of this response.