Given the long history of conflict associated with resource development in many parts of the world, I have been looking at whether resource development companies see a role for themselves in peace building. How do executives of multi-national resource companies think about their responsibilities in this area?

As a starting point I began my research talking with corporate executives in Europe, Asia, North America and Australia about what role they see for their companies in contributing to peace building in areas affected by conflict. My initial finding was that corporations are hesitant to participate in anything called ‘peace building’, due to the political connotations associated with the term. However they do see a role for themselves in contributing to peaceful resource development through the prism of corporate social responsibility (CSR). My search then shifted to ways in which we could make existing modes of CSR more effective in terms of facilitating peace.

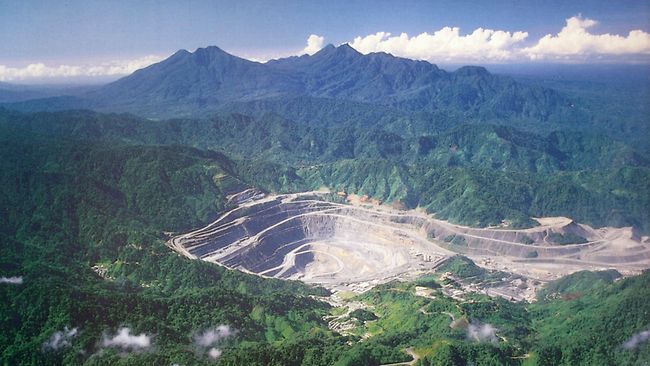

I began this search in relation to Bougainville and Papua. Both have long histories of conflict associated with the exploitation of natural resources where the extractive industry has been associated with aspirations for political autonomy. A key trigger of conflict in Bougainville and Papua has been the exploitation of resources for the benefit of a nation state that many feel culturally and politically marginalised from. Resources have provided a strong motivation for the nation state to hold onto control of resource rich areas, while at the same time offering the potential economic means for autonomy for those same areas.

Many Bougainvilleans and Papuans spoke to me with hope regarding the mineral riches lying beneath their land and the opportunities for a better future that they represent. Largely this hope resides in the potential for those resources to provide a momentum for political autonomy. Sharing their hope that resource development can offer, I’d like to raise some ideas my research in Bourgainville and Papua has generated regarding opportunities for peace in Melanesia that might emerge through large-scale extractive industries.

For this to be possible we must first recognise the highly contextual nature of resource conflict. In a region as diverse as Melanesia we need to find avenues for extracting resources that is attuned to the complexities of specific political histories, as well as traditional socio-economies and land tenure systems. The major risks in failing to do so are that resource development can: ignite conflict; exacerbate uneven development; intensify contests between national and local power structures; and increase intergenerational tensions. Despite the large scholarship that exists on the risks related to the resources curse, contributions regarding how these risks might be mitigated – or even turned into opportunities for peace – are much fewer. Given the very human desire for advancement and to improve the conditions of one’s life, it is important that more thought is put into how best to reduce the likelihood of conflict, rather than just assuming (or hoping) that communities will decide the risks are too great and leave the wealth in the ground.

The main limitation I have identified with existing models of CSR is that they are more focused on the distribution of material benefits, such as education and trust funds, than on engagement with the sources of injustice that may lead to violence. I don’t want to underestimate the value of material benefits, but they do not get to the heart of the problem, and will not be enough on their own to prevent conflict. This was certainly the case in relation to the Bougainville conflict and is also evident in Papua, where there have been strong links between resource development, historical injustice and regional inequality. Violence connected to extractive industries often transcends the immediate triggers (such as a dispute over compensation) but taps into much deeper, and at times highly emotive, issues of legacies of colonisation and cultural identity. Immediate concerns might be appeased by a rise in compensation payments, but underlying issues remain unresolved and likely to re-emerge.

Dealing with the underlying drivers of conflict might seem too difficult a task for resource development companies. However, it’s my feeling that engagement at this level opens opportunities for companies to contribute to peaceful development in ways that don’t just require ever-increasing financial payments to landowners. Having said this, I recognise that engagement of this kind is not easy, particularly where there is a hostile state involved.

In spite of the obvious challenges, examples of this type of engagement exist. BP’s strategy in West Papua has attempted to reduce the presence of the Indonesian military in the vicinity of its Tangguh LNG project to avoid the human rights violations and problems that have tainted Freeport’s mining operations for many years. This approach has salience for the possible resumption of mining on Bougainville, where executives of Bougainville Copper Ltd (BCL) and Rio Tinto might do well to seek redemption from Bougainvilleans by recognising and publicly stating the company’s involvement in the conditions which led to the civil war. Many Bougainvilleans I spoke to expressed a strong desire for an apology from BCL, but more than this, a statement about what BCL has learned from the past and how they plan to do things differently in the future. While this approach would no doubt be initially more complex than just working out a lucrative financial pay-off, it does provide an opportunity to address the underlying grievances that led to conflict in the first place. Even more important from the perspective of the company, it’s more likely to result in a viable mining operation that is less likely to be threatened by violence.

There are certainly a lot of problems associated with resource development, and it can be easier to identify the risks than the positives. However, it’s important not to underestimate the value of resource extraction, once the minerals have been identified – particularly where the wealth associated is connected not just to better standards of living but are also seen as a means of realising deeply held political aspirations.

Kylie McKenna is a postdoctoral Researcher at the ANU.

Are people ‘better off’ after so called development takes place?

There is a common thread that seems to insidiously entwine itself around the concept people in so called developed nations seem to view the aspirations of those in so called under developed nations.

To those in our ‘café latte’ societies that occasionally spare a thought and a few coins in favour of those in the ‘developing world’, it would seem impossible to consider that those who are viewed as being less fortunate could possibly be happy the way they are. Available statistics on health and education are easily translated into dramatic comparisons and emotive arguments by those who wish to fund overseas aid packages. Yet the undeniable evidence seems to point to the conclusion that many may end up being better off in the eye of the distant beholder.

Are those in our consumer society actually happier than those in the villages of a developing nation? The more we accumulate in material goods, the more unhappy many become. Salary and wages are always insufficient to purchase a larger house that costs more to run or a more modern, but gas guzzling SUV.

There doesn’t seem to be a happy medium whereby people can aspire to a better life through education and improved health without the ever present corollary of increased material expectations.

Mining companies are created by those who have the relevant training and a passion for extracting mineral resources to make a profit. Given that most developed countries have now discovered where their own mineral resources are, the obvious place to search for new deposits is in underdeveloped countries.

Yet the discovery of economically viable mineral deposits raises many questions. Primarily, the biggest question is: Who gets the benefits and who suffers any damages, permanent or temporary, to their environment?

Clearly, mineral extraction in a developing country does not in any way affect the environment of those who reside in the developed country that provides the capital and know how to extract the minerals. That can often lead to an: ‘Out of sight, out of mind’ mentality.

But what might happen if the mineral resources were underneath the backyard in the developed nation? In Australia currently, it’s a case of NIMBY – Not in my back yard!

Touring the Mid West of the US recently, I asked a local farmer about how he felt about the numerous oil wells and gas ‘fracking’ sites around his farm.

“Wal”, he reflected, “ Ah like drivin’ mah pickerp!”

Given that the US believes that it is on the road to creating self sufficiency in oil and gas, what effect might that have on the philanthropic potential of mining companies in the future?

Similarly, if a mining company wants to extract minerals in a developing country, will future concerns lead to a surcharge on the extracted resources to pay for the health and education of those who claim ownership of the resources? What happens if this creates a clear disparity between the haves (who are lucky enough to be sitting on the resource), and those who have not? Western concepts dictate that the state owns all resources under the ground and the state allots a fair share of the benefits to all citizens. In practice in most developing countries, this notion is usually only given lip service.

Locally, those Australian farmers lucky enough to have coal under their properties may reap a financial benefit in the sale of their property to a mining company. Their neighbours will not be so lucky however and will inevitably wind up with the dust and tailings and a degraded environment with plummeting land values.

The difference between Australia and a developing country is that we have (mostly) responsible governments that are able to be influenced by the majority of electors. Most developing nations do not have that opportunity.

What’s the answer? If we by persuasion or legislation, force mining companies to accept what in so called developed countries is the role of government, doesn’t this merely allow the government of the developing nation the opportunity to continue to reap the accrued benefits without being held accountable by their electors?

Mining companies are not set up to govern a nation or a region. If by default, they have to perform this activity, have they been effectively trained and are they then to be held accountable and if so, by whom and how? The film ‘Avatar’ encapsulates the problem most eloquently.

Hello Margaret and Tess,

Thank you very much for engaging with my ideas.

Tess, I like the term ‘cultural capacity building’ that you have used in your post. I developed a framework in my thesis which I called Interdependent Engagement which I think has a lot in common with the points you raise. However the strength of your post is that you do raise the issue of regulatory capacity which was a gap in my research. It was unfortunately beyond the scope of the public debate earlier this year to outline the logic and framework of Interdependent Engagement (as we only had 5minutes), but in that framework I put forward a methodology to help ‘navigate’ eight crucial areas where corporations need to develop this kind of ‘capacity’. These being: historical injustice; the denial of customary land rights, regional inequality and contests over resource wealth; cultural, political and economic marginalisation; human rights violations; community disruption: environmental damage; and aspirations to define the future. At least, these were the core areas I identified in the Bougainville and Papuan resource conflicts. As to regulatory capacity, yes- indeed. There has to be a role for States in developing this kind of engagement. But corporations also need to widen their responsiveness to States primarily, to communities affected by resource development. But this too has risks and limitations… happy to chat further.

Hi Kylie

I agree the framework you’ve developed does align with the ‘cultural capacity’ concept I had in mind, I like very much the areas you’ve delineated.

Yes I’d be happy to talk further on this because I think it’s a very important area and I also think that if it were possible to develop some tools or methodologies to assist corporations to develop these capacities then maybe this could be something our part of the world could share with countries elsewhere.

It seems to me that there may be a potential linkage here with the work Margaret & Robin are doing about engaging business in development and it would be good to explore that also…

Bye for now

Tess

Thanks Kylie for sharing these insights with us. It was partly in response to hearing you raise these issues in February that I started thinking about ‘cultural capacity building’ (could probably do with a better name) – i.e. assisting incoming companies to negotiate (or in the case of BCL renegotiate) the environment they are joining – yes they don’t want to get involved in ‘politics’ but the reality is that they are so perhaps what can assist is methodologies and pathways to navigate bearing in mind the need to avoid causing or (sometimes more likely?) exacerbating conflict. Here is the link to the item in which I raised this earlier in the year, would be interested to know your (and others’) thoughts.

Kylie

Congratulations. It’s great to see important findings from your PhD research so clearly captured in this blog which I hope will have a wide readership, especially compared with the numbers who have the time and inclination to read PhD dissertations.

I particularly appreciate the point you make about how negotiations between mining companies, governments and communities are usually strongly focused on financial payments — companies also focus on these in their published ‘responsibility and sustainability’ reports. Yet arguably more important impacts of mining operations on conflict, violence and health usually get much less serious attention. I think this is partly because, as you say, there are no easy solutions to be found. Effectively addressing these areas requires all parties (mining companies, national and local governments, landowners and communities) to cooperate and maintain that cooperation for the lifetime of the mining operation. In Melanesia, this seems like a dream (despite the admirable initiatives of a few companies) but it’s worth striving for if mining is to deliver stable and more prosperous communities.

Perhaps we’ll hear more about this at the forthcoming Mining for Development Conference in Sydney.

Margaret