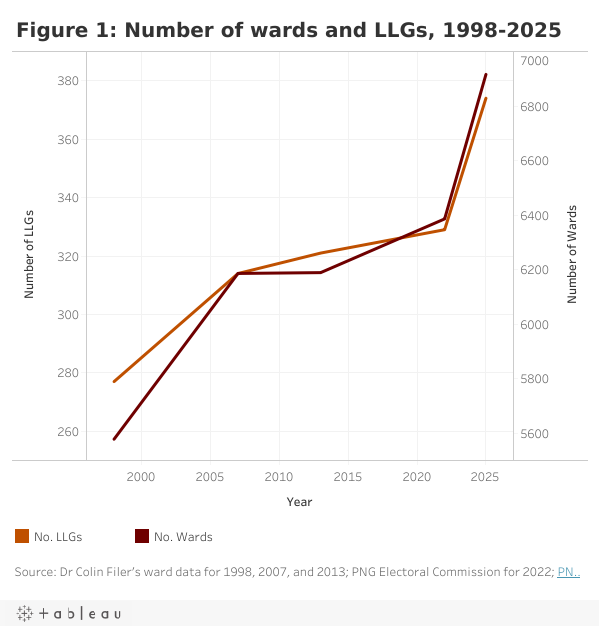

PNG’s lowest tier of government, local level governments, or LLGs, face a variety of problems. Key among them is that LLG numbers (and the ward electorates they comprise) have grown uncontrollably since being introduced in 1995. This has made running their elections this year problematic and has partly led to the inequitable distribution of grants over time.

In the past, PNG has run five LLG elections (1997, 2002, 2007, 2013 and 2019). Elections are meant to be held every five years in 20 of PNG’s 22 provinces, with representatives elected to the LLGs and wards. The provinces that do not run LLG elections are the National Capital District, which doesn’t have LLGs, and Bougainville, which has a different subnational government structure. (For a brief description of LLG functions, see here.)

Preparations for PNG’s sixth LLG elections are not going well. Originally scheduled for last year, then postponed to June 2025, the elections have been further delayed to September. This is a result of new ward and LLG proclamations by provinces following the 2022 general elections that have not been fully accounted for. By law, all of these proclamations have to be approved by the minister for the Department of Provincial and Local Government Affairs (DPLGA), and it appears they have been. These new wards and LLGs have required new rolls, new ballot papers and the coordination of more individual elections, making the job of the PNG Electoral Commission (PNGEC), which is conducting this election, more difficult and creating delays.

Another problem with this LLG election is that it was allocated K100 million by national government, lower than the K230 million budget initially requested. As in previous elections, several provincial governments are co-funding their LLG elections together with the PNGEC. Morobe, PNG’s largest province, however, has announced it will need additional funding from the national government.

For the provinces conducting elections, ward and LLG numbers have grown quicker since 2022 than in previous periods. Provinces have cited high population growthhigh population growth, the need for improved access to government services and better managementbetter management of funds as reasons for proposing new wards and LLGs. It is unlikely, however, that the new wards and LLGs were informed by the 2022 electoral roll or the 2024 census. And the new LLGs have done little to reduce variation in ward distribution. This year’s elections are expected to be conducted in 6,916 wards across 374 LLGs. (See the PNG Province Budget Database for a complete list.)

When an LLG is created, it is not immediately functional. Grants to LLGs give a sense of when a new LLG administration is established and the Province Budget Database now includes grant data for every LLG listed by Treasury. Since 2011, it took an average of 2.4 years between when Treasury listed a new LLG and when that LLG received a grant.

Also, since 2011, Treasury has added 69 LLGs and delisted 5, presumably reflecting these 5 being split into new LLGs. For the 379 LLGs listed in 2023 (it is unclear why Treasury lists more LLGs compared to the PNGEC), only 310 LLGs received grants reflecting the lag in new LLGs becoming functional. LLGs were entitled to 11% of the province grants provided by national government and have on average received this share annually between 2011 and 2023. This share increased to 15% from 2024.

There also appears to be an urban bias in grant allocation. The median real (adjusted for inflation) grant disbursed to urban LLGs has consistently been larger than the rural LLG grant median. Further, the largest grant disbursed to an urban LLG has been on average, 3.6 times larger than the largest grant disbursed to a rural LLG. This glaring disparity is explained by the 2008 LLG grant determination which stipulates that 79% of all LLG grants be allocated to rural LLGs while the remainder be given to urban LLGs. The rural and urban shares are then distributed to each LLG according to their respective district costs and populations. Rural LLGs have, however, consistently accounted for more than 90% of all the LLGs receiving grants, meaning rural LLGs have received less compared to their urban counterparts on an individual basis, irrespective of district cost and population.

It is entirely possible that urban LLGs face higher costs compared to rural LLGs. Considering population alone, grant sizes are not commensurate with LLG size. According to the 2022 electoral roll (notwithstanding its problems), the urban LLG median of 7,117 was much lower than the rural LLG median of 12,898 voters. Given rapid population growth over time, the 2008 grant determination has largely become ineffective in meeting the development needs of rural PNG and needs to be reviewed.

For rural LLGs, between 2011 and 2022, Mount Hagen in Western Highlands and Aramia Gogodala in Western province received the largest grant in different years, however, in 2023, it was Oro Bay in Oro province which received the largest grant (strangely Oro Bay’s grant more than doubled from 2022). Lae City Council in Morobe has consistently received the largest grant among urban LLGs. While the 2022 roll listed Mount Hagen as the largest LLG and Lae a close second, Lae’s grant of K2.6 million in 2023 was more than four times that of Mount Hagen.

It is worth mentioning that several LLGs receive revenue outside the grants provided to them by the national government. While data on this is patchy, the PNG Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative (PNGEITI) reports 31 LLGs as having received royalties from mining, oil and gas projects since 2013. Where data is available, for most LLGs, the royalties they receive are only marginally higher than their grants. Nimamar LLG of New Ireland, though, is by far the wealthiest LLG in PNG, in 2018 receiving K23.2 million in royalties from Lihir gold mine, in addition to its K0.14 million grant.

Many of the problems faced by LLGs can be traced to the DPLGA. Better coordination between the DPLGA and the provinces, the National Statistics Office (NSO) and the Departments of National Planning and Treasury is needed to plan for new wards and LLGs. For existing LLGs, the current grant determination has lost its effectiveness in addressing rural LLG needs and must be changed.

The previous article in this two-part series can be read here.

Thanks for the insightful discussion on Wards and LLGs. When we work in communities/villages, we link up with the Village Planning Committee (VPC) Chairman and his commiitte. How do they fit into the subnational governance structure. The Ward Coumcillors usually politicise service delivery and create division among villages, with many not benefitting from gvnt funding.