The Indonesia-Australia forest carbon partnership (IAFCP), launched with great fanfare by the two countries’ leaders in 2008, quietly petered out in mid-2014, having expended some $65 million. A decision to terminate it had been taken by Australia’s Labor government in early 2013, at which time its core elements were discontinued. The decision was taken abruptly, unilaterally, without public explanation and against the wishes of Indonesian governments at the national, provincial, district and village levels.

That the fortunes of such a high-profile, large-scale development cooperation program could have fallen so low constitutes a mystery, which I have sought to unravel in a policy paper released recently by the US-based Center for Global Development (CGD). The mystery is not who terminated IAFCP, but rather what gave them the motive and the opportunity to do it.

At the heart of the mystery was the Kalimantan Forests and Climate Partnership (KFCP), the single largest and most prominent element of IAFCP. KFCP was billed for a time as the world’s most advanced large-scale, site-specific REDD+ program—where ‘REDD+’ does duty for ‘reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, and (the ‘+’ part) promoting the conservation and sustainable management of forests and the enhancement of forest carbon stocks in developing countries’. KFCP was conceived in 2007 as a practical project to reduce emissions through avoided deforestation, reforestation, sustainable forest management and the trialling of performance-based payments to forest stewards of various kinds. It had all the elements of a REDD+ ‘demonstration activity’, as subsequently called for at the December 2007 UN climate change conference in Bali.

In announcing KFCP in September 2007, Australia’s then Coalition government said the project, sized at A$100 million over four years including A$30 million from Australia, would reduce emissions by an estimated 700 million tonnes over 30 years. It would preserve 70,000 hectares of standing peat forest, re-flood 200,000 hectares of drained peatlands and plant up to 100 million trees in re-flooded areas. Australia’s financial commitment to the project later grew to A$47 million but no other contributions materialised.

KFCP in the end disbursed somewhere toward A$40 million over the seven financial years to mid-2014. While its original, grandiose targets were quietly abandoned—as detailed in this mid-stream critique of the project by Erik Olbrei and Stephen Howes—it achieved much more than might be assumed, delivering valuable research, improving understanding of the concept of REDD+ at all levels and developing a degree of institutional capacity to undertake future REDD+ programs. KFCP might also have achieved good local economic and development outcomes in its host district of Kapuas, though time will tell whether these are realised and sustained.

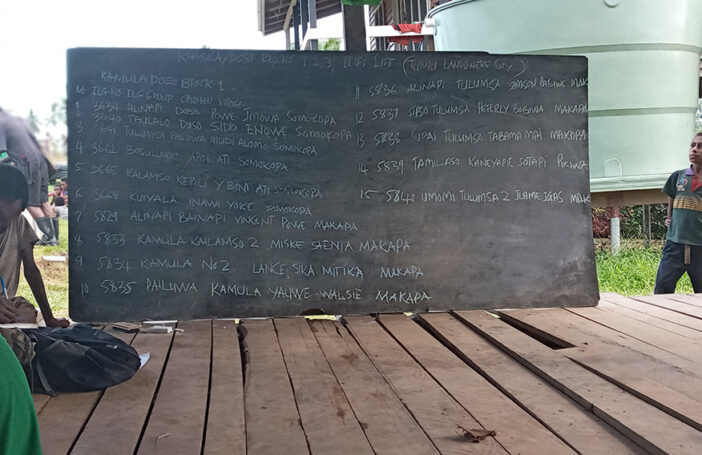

However, KFCP failed to achieve—in fact at no point attempted to achieve—its central objective, which was to trial the use of performance-based payments to effect quantified emission reductions. Piecework payments were made for limited reforestation and canal-blocking work, but no funded actions were related to measured reductions, even via rough proxy measures. And no links, therefore, were established between payments to actors and measured reductions. Moreover, the only actors considered relevant were local villagers, despite the evident importance of the Kapuas district administration in planning and implementing certain emission reduction measures.

Some observers [pdf] have described the recent history of REDD+ as a ‘narrative of disappointment’. That is certainly an apt description of the history of IAFCP—and particularly of KFCP. IAFCP did not merely fall short of what now appear to be risible early ambitions; it fell short of anything resembling reasonable ambitions for a A$65 million, seven-year investment, despite having almost five years’ worth of clear air. What factors account for IAFCP’s disappointing progress up to 2012, and in particular that of KFCP, which rendered IAFCP a target for preemptive termination by a government that might have been expected to reserve the task for its political opponents?

The blame cannot be sheeted home to an insufficiency of time, though a more generous allowance of time would certainly have been beneficial. And I argue that various other factors that might seem relevant, including deficient program governance, local disputes about land use rights in the KFCP zone and slow progress in the international climate change negotiations were either of little real significance or symptoms of more fundamental problems. My view is that IAFCP was vulnerable to termination—when its policy and budgetary environment became markedly less favourable in 2012 and 2013—primarily because its developer, the Australian government, failed at the outset to state and pursue a single, clear objective through KFCP. Loss of political sponsorship was a serious aggravating factor, but would have had less impact if the program had capitalised on its early political momentum.

KFCP’s central purpose at conception was not merely to test the technical feasibility of reducing emissions from peatlands with one or another intervention; it was to trial and cost the use of financial incentives to achieve emission reductions. Australia was in fact in a position to adopt a payment-for-performance ethos from the outset, using proxies for emission reductions until peat-carbon science advanced far enough to allow more precise measurement. Outcomes that could not be directly linked to proxies, particularly relating to local institutional development and alternative livelihoods assistance, could have been conceived as purchases made by the relevant local actors themselves (communities and the district government), using either the proceeds from performance-based payments (dividends) or advances on same (investments).

In practice, the Australian government hesitated to move on performance-based payments, allowing KFCP to become hostage to peat-carbon science and to national and global debates about REDD+ financial architecture, and functioning in large part as a traditional rural development initiative. The program could have made more substantial and instructive progress, even in its relatively limited five-year window, if it had given over-riding priority to the delivery of proportional payments for roughly-measured emission reduction actions to both communities and the Kapuas district government, while pursuing in parallel a peat-carbon research agenda with a view to refining cost estimates over time.

There is a ‘think big’ view that donor investments in REDD+ should be directed exclusively to the national level, as has been the practice of the Norwegian government in Indonesia, Brazil and elsewhere. On this view, site-specific pilot activities are simply a distraction. However, it should not be concluded from KFCP’s case that there is no place for guided, site-specific REDD+ demonstration activities. It is, I believe, unrealistic to expect that, once performance expectations are set and some readiness assistance provided, the production of avoided emissions will somehow begin of its own accord.

Ultimately progress in REDD+ will depend upon, not necessarily project-like investments as seen in connection with the Clean Development Mechanism of the Kyoto Protocol, but site-specific action across a series of sites. Investments in such action, whether by private investors, international public investors, or some level of government within the country concerned, will depend upon a prior understanding of what might realistically be achieved in a given landscape and at roughly what cost. Without this, no public or private investor will place money at risk. Essentially, the demonstration process is one of price discovery. A public ‘producer’ of emission reductions has to demonstrate value for money; a private one wants to be sure there will be an acceptable margin above cost before investing. KFCP in the end yielded no price information, but it could have.

I draw several general lessons that may be drawn from the IAFCP experience for any donor intending to act as a REDD+ project developer in ‘demonstration’ mode. First, concentrate effort on the main game, which is to work out how to counter the specific emission drivers in particular landscapes with financial incentives for cooperative action, and what this actually costs in practice. Second, ensure the participation of governments, especially at sub-national levels, so that they experience some of the costs and benefits associated with REDD+ interventions. Third, maintain policy neutrality with respect to national-level policy decisions on institutional and financing architecture. Fourth, vest responsibility for program development, financing and management in a single institution containing appropriately diverse but not warring perspectives. And fifth, accept and be held accountable for high standards of transparency and accountability in order to ensure that investments have genuine demonstration value and do not lose their way in the darkness.

Robin Davies is the Associate Director of the Development Policy Centre, and a member of CGD’s Working Group on Performance-Based Payments to Reduce Tropical Deforestation. His IAFCP paper and more than 20 others will inform preparation of the book Why Forests? Why Now? The Science, Economics and Politics of Tropical Forests and Climate Change, to be co-authored by Frances Seymour and Jonah Busch as part of CGD’s Initiative on Tropical Forests for Climate and Development.