Are Pacific countries moving towards greater regional collaboration – or is Oceania fragmenting into sub-regions? And what does “regionalism”, in a Pacific context, even mean?

For those of us working in Pacific regional organisations, these questions are not purely theoretical – they are integral to our future work streams, and encapsulate pressing political, social, and economic concerns.

This is what makes the current review of the Pacific Plan so topical and important. The review—which is being managed by the Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, but independently led by The Right Hon Sir Mekere Morauta, KCMG – is a wide-ranging, ambitious, and forward-looking assessment of attempts to strengthen regional cooperation and integration. When completed, we hope it will offer the region some visionary but pragmatic advice on the future of Pacific regionalism.

Why the review?

The Pacific Plan for Strengthening Regional Cooperation and Integration was first initiated out of a 2004 review of the Forum Secretariat by an Eminent Persons’ Group. This group proposed that the region needed a vision for its future. Leaders agreed, declaring at their meeting in Auckland in late 2004 that “the Pacific region can, should and will be a region of peace, harmony, security and economic prosperity, so that all of its people can lead free and worthwhile lives…” They endorsed the Pacific Plan the following year as a high-level framework for priority setting around this vision.

Although the plan presents a sound articulation of criteria for identifying areas in which regional (in contrast to national) action is warranted, it has perhaps become better known for its annexes, which present a list of regional “priorities”. These were last updated in 2009, as a medium-term set of 37 priorities, grouped under five themes: fostering economic development; improving livelihoods and well-being; addressing climate change; strengthening governance; and improving security.

The current review of the Pacific Plan, although essentially a routine exercise (as a living document, leaders proposed that the plan should be reviewed every three years), presents a timely opportunity to update the plan’s priorities – and also to take a wider look at the process of how priorities are set.

Asking the hard questions

With the assistance of a team comprising two Pacific country representatives and two international consultants, Sir Mekere has been asked to assess a range of factors related to the plan’s past success and future directions, including: its relevance and impact; its governance and priority-setting arrangements; how it meets the strategic interests and priorities of Smaller Island States; how it interacts with programming decisions by development partners; its ownership; and its implementation.

The review team began its work on these tasks in December 2012, and has recently reported back after an extensive country consultation exercise. From January to May, the team visited all 16 forum member countries and the two associate members (New Caledonia and French Polynesia), meeting with politicians, officials, civil society, academics, regional organisations, development partners, and private sector representatives to seek views on the future of Pacific regionalism.

A “diagnosis” for the region

The full presentation given by the review team at their Regional Consultative Meeting in Suva in late May is available on their website, but I will attempt to summarize some key points.

Firstly, it’s important to note that the review team hasn’t focussed on assessing the health of just the Pacific Plan—in their report back to stakeholders, they presented their diagnosis of the Pacific Region as a whole, acknowledging that the Plan’s content can best be assessed in light of its context.

The review’s country consultations highlighted the Pacific’s diversity and complexity, countries’ connectedness but also their fragmentation and isolation, and their widespread vulnerabilities, uncertainties, and dependencies — all of which create a unique pattern of demand for regionalism. There was also a widespread desire in the region for paths to development that reflect existing Pacific island natural, social and financial capital.

The team observed a continuing appetite for regionalism across Pacific countries, and a continuing desire for a common political forum to debate issues affecting the region’s future. However, this did not reflect unbounded enthusiasm for growing regionalism; stakeholders were very realistic about the long term nature of any move along the spectrum from current levels of cooperation to more substantial integration. Furthermore, there was no clarity or consensus on just how integrated Pacific countries want to be, although there was widespread agreement that sub-regionalism was helpful and effective, and an important part of a wider regional agenda. Above all, there was consensus that the Pacific Plan in its current form did not create the right platforms for dialogue, or have the right supporting institutions for advancing regionalism.

A new framework?

The review team suggested that, rather than being cast as a “regional development plan”, or a check list for donor funding, the plan should be seen as a framework for advancing the process of regional integration (and regionalism more generally) through informed political choice and strategic change.

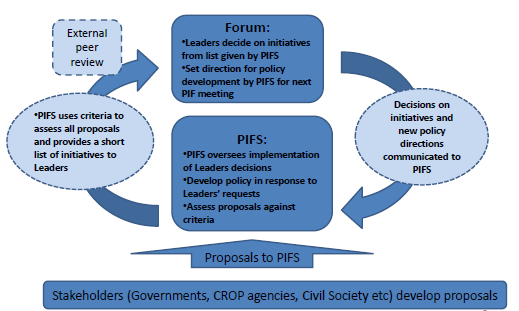

They proposed a new process for priority setting and reporting back to leaders, shown here. While perhaps not revolutionary, this process does envisage some substantial changes from the status quo in order to make regional priority setting more robust, more transparent, and more oriented towards political leadership than bureaucratic capture.

They proposed a new process for priority setting and reporting back to leaders, shown here. While perhaps not revolutionary, this process does envisage some substantial changes from the status quo in order to make regional priority setting more robust, more transparent, and more oriented towards political leadership than bureaucratic capture.

To move from current practices to this new framework, substantial and systemic change would be required. More details of the team’s proposals for such change will emerge when they present their draft report to the Pacific Plan Action Committee in early August, which will be further considered by leaders at their annual meeting in the Republic of Marshall Islands in September. Yet even when the review is over, much of the work will have just begun: any transition to a new way of business under the Pacific Plan is unlikely to be instantaneous or easy, and will require considerable political and official support.

Nevertheless, the Pacific Plan review team has thus far hinted at a future Pacific Plan:

- that is less a wish list and more a pragmatic framework,

- that articulates clear values that Pacific countries can present in regional solidarity in international fora and also reflect in their own national policies, and

- that has a small but well-justified set of priorities that require regional collective action to achieve tangible, region-wide benefits.

This would truly be a framework that promotes future regionalism not for regionalism’s sake, but because of the clear benefits that it would bring to Pacific governments and their peoples.

Seini O’Connor is the Pacific Plan Adviser at the Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat (PIFS). The views presented in this post are those of the author, and not of the Pacific Plan Review Team, which is independent from PIFS and reports to the Pacific Plan Action Committee as its steering committee.

Just for the record. The statement “The Pacific Plan for Strengthening Regional Cooperation and Integration was first initiated out of a 2004 review of the Forum Secretariat by an Eminent Persons’ Group” is not technically correct. If records still exist then one will see that the seed was first sown during the 2003 Heads of CROP meeting. 2004 was identified as the 10th Anniversary of the Madang Vision Statement and it was thought appropriate to review and revise the vision for the Region. (Look at the 1994 Madang Vision and you will understand why). The PIFS (Noel Levy) ran with the idea to the Auckland Forum meeting. Before you could catch your breath we had an EPG crafting an aspirational Plan without a clear implementation Strategy. The rest as they say is history. Be interested to see the results of this most recent repair job. With a diverse region and grouping of countries I believe that less is more. Provide a simple vision which we all can agree on rather than a detailed, prescriptive plan which attempts to incorporate every exception. For a resource and capacity poor region we seem to spend a disproportionate amount of time and effort planning and reviewing and not enough implementing the very different and often unique priorities. Just check out the situation on the ground if you think I’m off the mark.