The Kiribati Social Development Indicator Survey (SDIS) 2018-19 was officially launched on 10 March. The SDIS is the first Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) implemented in Kiribati. MICS are arguably the most important source of statistically sound and internationally comparably data on women and children, and the SDIS contains additional Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) modules. This blog highlights three insights from the new Kiribati SDIS, with a focus on labour mobility.

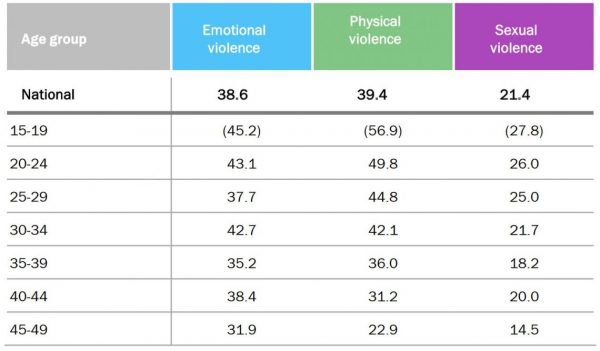

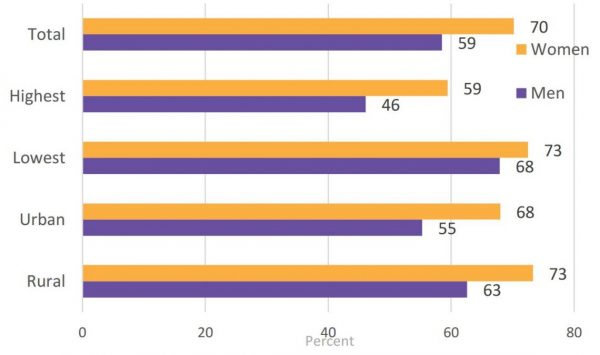

First, two in three i-Kiribati women aged 15–49 who were ever married or partnered have experienced intimate partner violence, more than half in the last 12 months. The survey has a number of questions on gender and domestic violence and most of these results are deeply disturbing and worth considering carefully. 55 per cent of those who experienced violence have never sought help or told anyone. The percentage of women who experience emotional, physical, or sexual violence by their husband or partner, in the last 12 months, falls as women get older (see, for example, the table below). 70 per cent of women and 59 per cent of men believe that wife beating is justified when a woman goes out without telling her husband, if she neglects the children, if she argues with or refuses sex with her husband, or if she burns food. 47 per cent of men and 41 per cent of women caretakers believe that physical punishment is needed to bring up, raise, or educate a child properly, a dynamic which likely feeds the high rates of intimate partner violence.

Figure 1: Percentage of ever-married women who have experienced emotional, physical or sexual violence by any husband/partner in the past 12 months

Source: Kiribati: Social Development Indicator Survey 2018-19 Snapshot of Key Findings

Source: Kiribati: Social Development Indicator Survey 2018-19 Snapshot of Key Findings

One concern which has come from the participation of i-Kiribati women in Australia’s labour mobility schemes is that a number of participants are leaving their former relationships or have found new partners. Anyone who has been through a separation or divorce would not wish that level of heartbreak, stress, and all the other associated challenges on their worst enemies, let alone on their children. Yet, one cannot look at these numbers and rule out the possibility that some of the participants may have been in abusive relationships, and that employment opportunities and broadened social networks are offering a pathway out. Some of the best tools for improving gender equality are getting women into good jobs and reversing traditional care norms, especially when society does not naturally tend toward either. Labour mobility may well be supporting or indeed enabling such progress.

Figure 2: Attitudes toward domestic violence

Percentage of adults age 15-49 who justify wife beating for any of the following reasons: she goes out without telling him; she neglects the children; she argues with him; she refuses sex with him; she burns the food, by sex, wealth quintile and area.

Percentage of adults age 15-49 who justify wife beating for any of the following reasons: she goes out without telling him; she neglects the children; she argues with him; she refuses sex with him; she burns the food, by sex, wealth quintile and area.

Source: Kiribati: Social Development Indicator Survey 2018-19 Snapshot of Key Findings

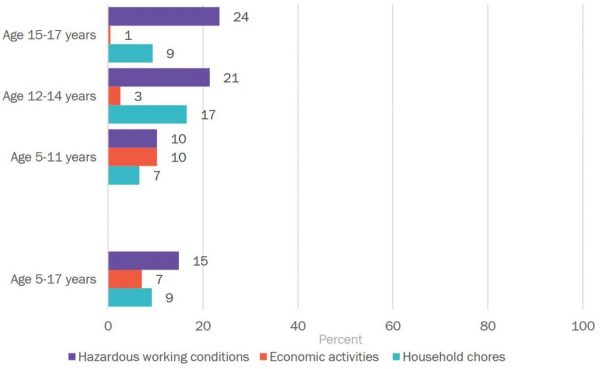

Second, the survey is incredibly helpful for understanding how i-Kiribati children are doing. For example, one in five women aged 20–49 were first married or in union before the age of 18. The prevalence of child marriage is three times more for women in the lowest quintile (that is, 30 per cent for the poorest 20 per cent of the population) than it is for the top quintile (that is, 10 per cent for the richest 20 per cent of the population), and much lower for those who have completed secondary education (8 per cent, as compared to 36 per cent for those without any education or only pre-primary). The survey also contains useful information on child labour, which can severely limit children’s ability to develop to their fullest potential. One in four children aged 5–17 are engaged in child labour (see page 49 here for definitions). Prevalence is higher for boys (31 per cent) than girls (20 per cent), and highest for those aged 12–14 (36 per cent). Strikingly, the most common form of child labour is that in hazardous working conditions, rather than household chores or other economic activities. 24 per cent of all children in the 15–17 cohort work in hazardous activities. Again, these numbers are interesting for thinking about labour mobility. The baseline levels of child labour in and out of the home are reasonably high in Kiribati. With an absent household member, these rates may increase further if children are forced to take on board some of the duties of the absent member.

Figure 3: Percentage of children age 5 to 17 years engaged in child labour, by type of activity and age

Source: Kiribati: Social Development Indicator Survey 2018-19 Snapshot of Key Findings

Source: Kiribati: Social Development Indicator Survey 2018-19 Snapshot of Key Findings

Third, this data can be used by researchers. This should not be notable, but the fact that it is says a lot about the state of data and evidence-based policy in the region. A wealth of household income and expenditure surveys, demographic and health surveys, population and housing censuses, and other large-scale quantitative data products have been collected across the Pacific for the last few decades with support from the Pacific island or donor country taxpayer (for example, browse this microdata library of 580 surveys, of which 551 are “not available”). Yet most are inaccessible to researchers and the general public for a variety of reasons I will not elaborate on further in this post. This is not only a waste of public money but deeply undermines accountability and policy development, something certainly not needed in a region home to a number of fragile states. By hosting the data online through UNICEF, the SDIS is actually available for researchers and policy analysts to use. The same has been done for the recent Papua New Guinea DHS, which was the first from the Pacific to make it onto the DHS website and not require one to manipulate backchannels and convince bureaucrats (assuming you get in touch with them) to release the data.

Despite this immense progress in the last few months, there is one further small change which could dramatically increase the utility of these data. Pacific governments remain overly cautious about statistical disclosure issues (such as, identifying individuals) and retract a lot of information needed by researchers, particularly geographic information. This requires assuming ill-will on the part of the researcher or policy analyst, and some rather creative ideas on the horrible things we might do with such information. But experience shows us that such abuses are exceptionally rare. Most if not all researchers just want to publish papers and make a positive contribution. The immense benefits of information sharing almost always exceed the potential (and virtually never realised) costs. As geospatial (including satellite) data are increasingly available and used by social scientists, ensuring that disseminated survey and census products make fine geospatial information available will be crucial to keep the region up to date and maximise the returns to ongoing data investments. Future data releases, and those mentioned in this blog, should include the finest geographic information possible, specifically the village or GPS coordinates.

Overall, the results of the Kiribati SDIS reinforce just how important data and evidence are for thinking about and guiding policy in the region. For example, the SDIS information on water, sanitation, and hygiene will be incredibly helpful for planning should COVID-19 reach Kiribati. Projects like SDIS also illustrate the value of persisting to improve the Pacific data and evidence ecosystem. This is especially true when small policy changes – like simply hosting the data in accessible places online, and not restricting geospatial information – can have such transformative effects on uptake, potential uses, and correcting misperceptions.

Read the snapshot of key findings here or the full report here, and access the data here.