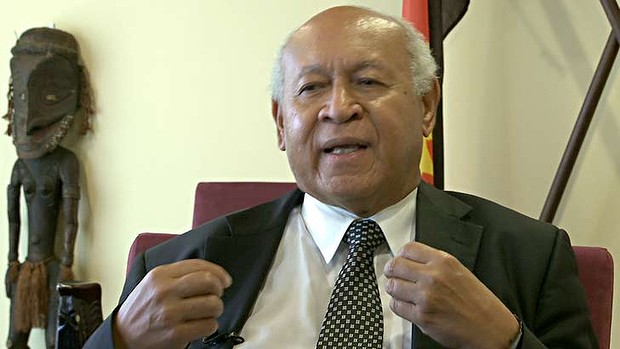

Sir Charles Watson Lepani KBE, who passed away on 10 January, was the last surviving member of Papua New Guinea’s famous “Gang of Four”, four young bureaucrats who, at the time of independence, seemed to be running the country.

Charles Lepani had an amazing career, one that intersected with, shaped and was shaped by many of the key developments and events PNG has experienced since its independence half a century ago. Fortunately, he gave no fewer than three compelling and informative interviews looking back at various aspects of his career, which I recommend to anyone interested in PNG’s history (links below).

Born in the Trobriand Islands — in the culture of which he was always strongly grounded — Lepani won an Australian government scholarship to go to high school in Charters Towers, Queensland (a life-changing experience he said, especially his observation of white men doing manual labour) before studying economics at the University of Papua New Guinea and then industrial relations at University of New South Wales (on an Australian Council of Trade Unions scholarship with none other than Bob Hawke as mentor).

Back in PNG as a trade unionist, and then as a Wage Commissioner, he became part of the pre-independence push to more than double urban wages. In this, he went head-to-head with Australian economists Ross Garnaut and John Langmore who argued for wage restraint to protect government fiscal capacity and to enhance economic competitiveness. Lepani, who enjoyed the backing of a pro-union government, won those battles decisively, arguing, with the support of heterodox Australian economist Chris Gregory, both that the profitable Australian companies operating in PNG could afford to pay more and that formal sector workers needed to be paid more to support their wantok.

He then moved to head the new and powerful National Planning Office at a time, just after independence, when bureaucrats called the shots. The constrained fiscal circumstances within which government operated and the limited funding available for rural development changed his perspective on the wages issue, and a major report he co-authored on the PNG economy in the mid-eighties reflected this.

After a stellar early career in government (including five years as head of Planning), he returned to study in 1980, undertaking a Masters in Public Administration at the Harvard Kennedy School. Back in PNG, he turned to consulting, where he was again a pioneer. Among his influential works were the 1985 report on the PNG economy mentioned above, co-authored with Charles Goodman and David Morawetz and, almost two decades later, a 2004 official review of Australian aid.

In between those two reports and his other consulting activities, Lepani took on a wide range of academic, government and corporate assignments. From 1986 to 1990, he headed the Pacific Islands Development Program at the East-West Centre in Hawaii. From 1991 to 1994, he was PNG’s Ambassador to the European Union. In 1996, he became CEO of Orogen, which held the PNG’s government’s equity shares in various resource projects. While CEO, he successfully floated the company and sold off 49% of its shares.

Then, in 2005, he became PNG’s High Commissioner to Australia. It was the position he held for the longest period of time, serving until 2017, retained in that role by his government beyond the compulsory retirement age. Along the way, he became the longest-serving representative of any country to Australia, and took on the role of the dean of the Canberra diplomatic corps. He represented PNG with charm and tenacity, and with the benefit of his accumulated experience and wisdom. We published one of his speeches, from 2013, in which he said:

For those who concern themselves that PNG is too poor, ridden with crime, and all manner of pestilence and affliction, we accept these as challenges for us to resolve and we will continue with our confidence in our country and that we are a proud and a responsible member of the international community with a vibrant democracy.

A powerful combination of humility and directness.

Charles Lepani was always up for a good discussion. We had both co-authored official reports on Australian aid to PNG (mine was in 2010). He was something of an aid sceptic and definitely a supporter of less rather than more aid. The generation who took PNG to independence appreciated Australian aid but saw it as a temporary feature of the relationship between the two countries.

In an email exchange after his return to PNG, we discussed Australia’s new Pacific Engagement Visa (PEV). He told me that “there were two things I was keen on achieving in my 12 years as High Commissioner of PNG in Australia: start reduction of Australian aid to PNG, and visa free entry to Australia”. He said that he regarded the PEV as the next best thing to visa-free entry for Papua New Guineans and so was strongly in support of it.

Back in PNG, though officially retired, he took on various assignments. His final public service role was as chair of the Eminent Persons Group that drafted a new Foreign Policy White Paper.

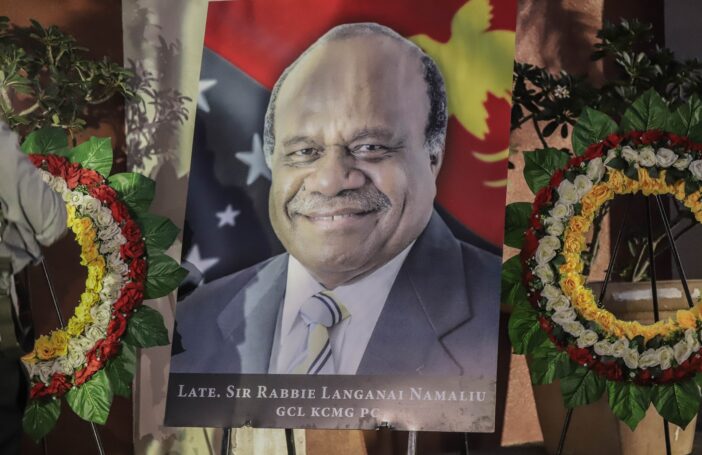

Such is the pull of politics in PNG that the other three members of the Gang of Four — Anthony Siaguru, Rabbie Namaliu and Mekere Morauta — all became MPs, and indeed went on to become Ministers or even Prime Minister. Lepani was born into politics: his father, Lepani Watson, was a member of PNG’s House of Assembly before independence, and then Premier of Milne Bay after independence in the 1980s. Not surprisingly, the son also had a tilt at becoming an MP. He first stood for office in 1982 (in the seat of Kiriwina Goodenough). He came third. He didn’t try again until 40 years later, in 2022, when he was again unsuccessful — this time coming fourth in the contest to become Governor of Milne Bay. Speaking to him after the 2022 elections, he didn’t seem to mind the loss too much. And his wide-ranging career was a blessing for his country. PNG needs good politicians but it needs good leaders in all areas.

On a personal level, he was not only charming but a skilled raconteur (those interviews have some very amusing anecdotes). He contacted me a couple years ago in Port Moresby. In the course of an entertaining dinner, he thanked me for the Development Policy Centre’s PNG blog articles and databases, and the work we do with UPNG. He said it was important for the country. That meant a lot to me. In general, I would say he came across as somewhat disillusioned — he had certainly seen much better days, and much better governance — but not despairing. He retained his sense of humour, and his sense of hope.

He was also a great family man. He was married twice, and had two children with his first wife, Barbara, and three with his second, Katherine, a much-valued colleague at the ANU.

Charles Lepani had an amazingly diverse career and full life, and ran both well. He will be much missed in Australia as well as in Papua New Guinea.

You can listen to three interviews conducted with Charles Lepani at PNG Speaks (2015), National Library of Australia (2011) and Princeton University’s Innovations for Successful Societies (2010). You can read two of his speeches on the Devpolicy Blog: the one mentioned above on PNG-Australia relations, and a tribute to his good friend and former prime minister, Rabbie Namaliu.

Thanks Stephen,

This is a heartfelt tribute to Sir Charles Lepani. His remarkable career and contributions to PNG, both nationally and internationally, are well captured in your reflection. I appreciate how you highlighted his views on aid, the Pacific Engagement Visa, and his deep sense of humour, humility, and family values.

Regards.