Energy poverty is widespread in Pacific island countries, including PNG. It is estimated that 70 percent of households in the region do not have access to electricity and 85 percent do not have access to clean cooking energy technology. This is low by international and regional standards, being equivalent to access rates in sub-Saharan Africa, and slightly below the average for low income countries (despite higher income levels in much of the Pacific).

Energy poverty, or the lack of access to modern energy services, is a concern given its development impacts. Limited access to electricity is a barrier to economic activity and the delivery of key public services, including health, education and infrastructure services. At the household level, un-electrified households have been shown to spend more on energy than do households with access to electricity. This commonly takes the form of fuels for lighting, such as kerosene.

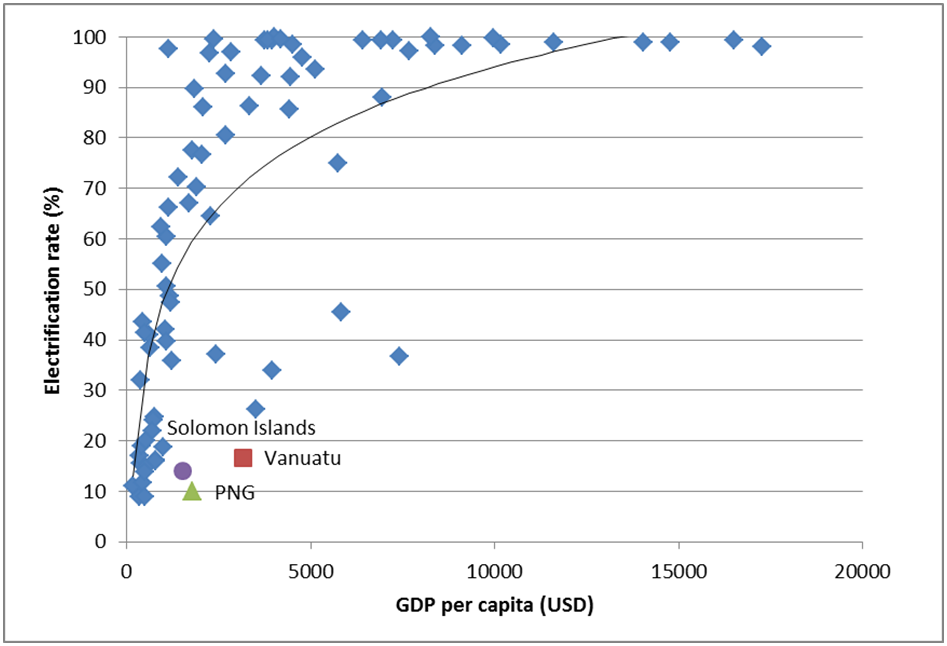

In a paper that was recently published in Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews (available here [pdf]), I examine reasons for the low rate of access to electricity in the Pacific, and assess whether we are heading in the right direction – i.e., is access to electricity in the region improving? The short answer, based on the available evidence, is ‘no’. There has been very limited progress in widening access to electricity in rural areas – which is where the vast majority of Pacific households without access to modern energy services reside. This is particularly true in Papua New Guinea (PNG), Solomon Islands and Vanuatu, where electrification rates are lowest, being below what would be expected given per capita income levels (see Figure 1). These countries also feature high levels of population growth.

Figure 1. Access to electricity and GDP per capita

There are a number of reasons – elaborated in the paper – for why access to electricity in rural areas is so low in the region.

One relates to spending on rural electrification. The high upfront cost associated with rural electrification means that subsidisation is generally required (this is subsidisation for the upfront cost of distribution lines, or wires, and additional generation capacity – ongoing supply costs can be met through user fees, although often aren’t, as detailed below). But government resources that are dedicated to rural electrification in the Pacific are limited. In Solomon Islands for example, where it is estimated that just 12 percent of the population has access to electricity, the rural electrification in 2012 totalled just US$1.34 million (and this represented an increase on previous years). In Fiji, rural electrification spending is less than US$10 million, while tax concessions and contingent liabilities associated with grid-based investments measure in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

The very ambitious renewable energy targets of Pacific island countries, I argue, are a concern in this respect. Governments, in order to meet these targets, will require substantial investment in renewable technologies. But the bulk of this investment will be in areas where there is already access to electricity – rural electrification has only a very minor impact on enabling countries to meet renewable energy targets, given low levels of demand for power in rural areas. There is, therefore, the potential for renewable energy targets to divert attention and the funding of governments and development partners away from rural electrification.

There are already indications that this is occurring. At the Pacific Energy Summit in March 2013 (a critical review of which was provided on this blog), governments of Pacific island countries provided a list of current and proposed projects in the energy sector. The list is not a comprehensive overview of spending in the energy sector, but it does indicate projects for which Pacific island countries seek funding, and therefore provides insight into the priorities of governments. Projects that focus on expanding access to modern energy services (including electricity) accounted for 4 percent of the total value of projects on the list. The vast majority of projects involve power generation for urban electricity networks (known as “grids”) using renewable technologies.

The reasons for limited progress in widening access to electricity are broader, of course. One important factor is the way in which existing subsidies – both explicit and hidden – are spent. The bulk of subsidies are currently directed toward maintaining low residential electricity prices – primarily for urban electricity grids. In other words, subsidies are directed toward maintaining low prices for households that already have access to electricity, not for broadening access to electricity. These subsidies can take the form of periodic injections of capital to power utilities that are in financial distress, tax breaks, loan guarantees or explicit budget allocations. These universal subsidies disproportionately benefit high income households, and do not accrue at all to un-electrified households (a more effective arrangement involves lifeline tariffs/prices for low levels of use, which better target low income households – this is explained in the paper).

A related issue is the common practice of urban households cross-subsidising electricity consumption among rural households through a uniform electricity tariff/price. Cross-subsidisation has the effect of limiting the extension of electricity grids into rural areas, as the cost for the power utility of supplying a rural household may exceed the electricity tariff/price. This means that the electricity utility has no commercial incentive to extend the electricity grid – even where the upfront cost of this extension is subsidised by government.

Indeed, incentive problems are not only the result of cross-subsidisation. A recent benchmarking survey of Pacific power utilities suggests that there are six utilities that make a loss on every unit of power that they sell. For these utilities, there is no commercial incentive to expand access to electricity – to do so would only result in further financial losses.

Regulatory reform is required to address such issues. Indeed, a key argument of the papers is that Pacific island governments, to expand access to electricity, must reform institutional arrangements in the power sector.

The points raised so far highlight the barriers to the extension of urban and peri-urban electricity grids into rural areas. But what about rural electrification in areas where the electricity grid will never extend? The geography and population distribution of countries like PNG, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, FSM and Kiribati makes the installation of off-grid systems crucial. Yet subsidies directed toward electricity consumption in urban areas far outstrip government funding for installation of off-grid systems, such as village-based diesel generators or solar home systems.

These priorities should be reversed. In the paper, I argue for increased funding to be directed towards rural electrification using off-grid systems, and for these resources to be made available by reducing universal subsidies for power consumption among households connected to the electricity grid/network. To widen access to electricity in remote areas, however, institutional arrangements that facilitate the maintenance of off-grid systems must be established. This is likely to be a challenge. Past donor and government-funded off-grid rural electrification projects have often had limited impact due to the failure of off-grid systems. I canvas a number of approaches that could be used to ensure adequate maintenance – notable among them being a concession model where a private company or large-scale community cooperative is responsible for the operation and maintenance of off-grid systems. The approach is certainly not a panacea, but its effective use in parts of Africa and Latin America suggests that it warrants consideration.

This blog post summarises a journal article published in Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. A copy of the paper can be accessed here [pdf].

Matthew Dornan is a Research Fellow at the Development Policy Centre.

As an individual, I agree with the plan as it will provide potential opportunity to the rural communities in PNG. I will solve more issues like bringing to the rural level socio-economic activities.

The PNG Department of Petroleum and Energy with the support and participation of key development partners recently hosted a workshop to consult on the National Electricity Roll-out Plan and its delivery. The PNG IDA Project Office under the Department of Works was represented.

The IDA Project Office is specifically interested in the development of a ‘Power Sector Infrastructure Strategy’ as envisaged in the Draft IDA Bill (Part IV, Division 1 refers) and a ‘5 Year Power Infrastructure Plan’ (Part IV, Division 2 refers).

The IDA Project Office notes that under the 2014 Budget, PNG Power Limited (PPL) has two ‘strategic’ infrastructure being the PNG Towns’ Electricity Investment Project at K75.8 million and Upgrading the Power Distribution System of Ramu Grid at K28 million.

While I agree with your conclusions with regard to renewable energy as a solution for Small Islands Developing States (SIDS) of the Pacific, the argument is different. One of the key barriers to electrification, especially rural electrification in the Solomon Islands is land and land ownership. It is only in areas adjacent to the main population centres where there is an effective cadastre, while the remaining land is in customary ownership. As an opinion the existing land in customary ownership will always remain in customary ownership which makes developing any large scale infrastructure difficult. The issue then becomes how you align traditional land ownership patterns with electrification; there are several options that come to mind. One is the Pelena Energy model whereby the scale of electrification, such as mini hydro, is aligned with the geography of a community or adjacent communities. Another is individual electrification solutions such as solar home systems, which have minimal impacts on communal land and the traditional urban approach whereby a diesel genset is installed on alienated land and the associated distribution network is run in a defined road reserve. This is perhaps one of the reasons why diesel gensets have historically been the default solution in parts of Pacific, i.e. they occupy a small area of leaseable alienated land. I also acknowledge that diesel gensets have a low capital cost and were, but no longer, cheap to run.