Introduction

It is said that those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it. PNG has experienced massive revenue growth over the past decade. How has it made use of that revenue, and what lessons can be learned from those choices?

As part of the PNG Promoting Effective Public Expenditure (PEPE) project carried out by the National Research Institute (NRI) and the Australian National University’s Development Policy Centre, an analysis was done on the budgetary trends in PNG of the last decade. The outcomes of the analysis were presented at a Budget Forum on 12 September 2012 at NRI (click here for videos and presentations). This brief (published as an NRI Spotlight Article) summarizes the analysis and highlights key lessons to be learned for the 2013 and subsequent budgets.

Synopsis of past budget trends

PNG has experienced a rapid rise in revenue over the last decade. In nominal terms, national revenue nearly tripled to an estimated K10.2 billion in 2012 from K3.6 billion in 2003. Adjusting for inflation, revenue increased by about 75 percent. Revenue growth was stronger before the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) (about 8 percent a year from 2003 to 2008 after inflation), but has nevertheless been impressive since then (at 5 percent a year from 2008 to 2012, again adjusting for inflation). Minerals revenue (mining and petroleum tax and dividends) was very strong before the GFC (annual average of 25 percent after inflation), but has fallen since. Aid did little more than keep pace with inflation. Other sources (including personal income tax, trade taxes, and the GST) have grown strongly throughout the last decade, and at an average real rate of 10 percent since the GFC, indicating the broad-based nature of PNG’s rapid revenue growth.

This large increase in revenue led both to improved public finances (including a fall in public debt and an improvement in fiscal balance) and also a significant increase in public expenditure, mainly post-2007. Adjusting for inflation, total expenditure increased by less than 5 percet between 2003 and 2007. By 2012, however, total expenditure was almost double its 2003 level (a 94 percent increase), even after accounting for inflation.

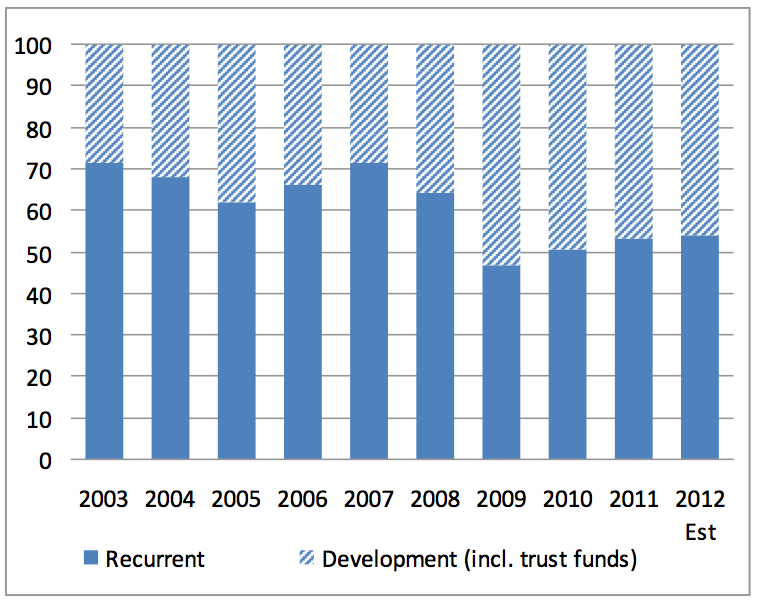

As Figure 1 below shows, government spending is increasingly in the development rather than the recurrent budget. Recurrent budget as a share of total expenditure fell from two-thirds or more in the early 2000s to about half by 2012. Unlike ten years ago, the development budget is now largely financed by the Government of PNG rather than by donors.

Figure 1: Share (%) of development and recurrent spending in total expenditure

Trust funds were used in the middle of the decade to mop up a surge in revenue and direct it to various projects, but this is widely viewed as not having resulted in productive spending.

Spending at the district level by MPs increased rapidly in the first part of the last decade, but has since stabilised, and is now only about 2 percent of total spending.

In the recurrent budget, spending on goods and services has grown faster than spending on salaries. Over the course of the decade, national government spending has increased by more than provincial government spending. The national government is responsible for about 90 percent of total goods and services spending, whereas salary spending is evenly shared between national and provincial governments.

One way to summarise the experience of the last ten years is to observe that the total increase in revenue over this period, compared to what PNG would have seen if revenue had stayed at its 2003 level, has been K32 billion. Where has that that K32 billion gone? One-quarter (K8 billion) was needed just to keep pace with inflation. After adjusting for inflation, just over half (K17 billion) was used for additional development budget and trust fund projects. K2 billion was used to improve the fiscal position, and less than K5 billion was used to meet recurrent needs.

Figure 2: Where PNG’s additional revenue over the last decade has gone

Positive points

These trends have resulted in a number of positive developments in PNG. Compared to ten years ago, the national government has almost twice as much revenue (after inflation). It also has twice as much choice in how to spend each Kina because the share of salaries, interest and aid (all areas over which the government has no or very limited discretion) has halved. Importantly, spending in priority areas of national development, such as health, education and roads maintenance, has risen sharply.

Negative points

Expenditure levels did not kept up with population growth prior to the last decade, and even now are only back to the per capita levels of expenditure seen at Independence. All areas of public expenditure have increased – there is no sign of a shift in focus to priority areas. And, despite increases in spending to date, there are still massive funding gaps in critical areas. For example, to fully achieve targets in education and maintain priority national roads, an extra K1 billion and K1.4 billion, respectively, is needed annually (according to the partnership agreements signed between PNG and Australia). Filling these gaps largely requires increases in recurrent funding, whereas it is the development budget which has been increasing rapidly to date. To add to the challenge, revenue growth in the next few years may be slow due to subdued global economic conditions, the maturing of current mines and oil fields, and delayed revenue from new minerals projects due to tax arrangements.

Challenges ahead

Seven lessons and questions can be drawn from this analysis for the future.

First, given still scarce and limited resources, the Government needs to prioritise. The priority should be plugging funding gaps in priority areas to achieve national development targets.

Second, the key funding gaps – education, law and order, health, roads maintenance – are in the recurrent budget, so there needs to be a shift in the focus of public spending away from the development budget to give more priority to recurrent spending. More funding should be allocated for the maintenance of existing public infrastructure, for example, rather than building new roads or other assets.

Third, and related, in the last decade the aim apparently has been to maximise the development budget. This is not the same as maximising development! Indeed, there is a question as to whether the recurrent and development budgets should still be separate parts of the overall annual budget or be combined, as they once were. This obviously has implications for the current roles of the Department of National Planning and Monitoring which formulates the development budget and the Department of Treasury which formulates the recurrent budget.

Fourth, large funding gaps cannot be filled in a single year. Consideration should be given to adopting medium-term multi-year expenditure frameworks with sectoral targets.

Fifth, more debate is needed around decentralisation. At the moment, the trend is towards greater centralisation of spending, and away from provinces. Does this make sense? Should the provinces be better funded, or should funding be direct from the central government to service delivery facilities, as in the case of the school subsidy?

Sixth, more revenue effort is needed to promote broad-based revenue generation, both by increasing the revenue base and by preventing revenue leakages through tackling tax evasion. Although revenue growth in the last ten years has been strong, it has already slowed, and, without revenue reforms, a further slow down is possible.

Seventh, more evidence is needed on expenditure effectiveness. There has been little research undertaken on this in this last ten years. The major facility and expenditure tracking survey which the NRI and ANU are currently undertaking as part of the Promoting Effective Public Expenditure project will help shed light on what impacts increased expenditures have had on the ground.

This post was originally published as a National Research Institute Spotlight Article and is part of the Promoting Effective Public Expenditure (PEPE) in PNG Project.

Stephen Howes is Director of the Development Policy Centre. Andrew A. Mako is currently working on the PEPE expenditure tracking survey.

The major facility and expenditure tracking survey which the NRI and ANU are currently undertaking as part of the Promoting Effective Public Expenditure project is an important mechanism that should help shed light on what impacts increased expenditures have had on the ground.

It is hoped that the survey will also consider the effectiveness of the Government’s public procurement system as the means of delivering expenditure. In PNG significant effort has been invested in evolving a public procurement system that should be open, transparent, free from corruption and delivers value for money. If the public procurement system is efficient and effective, chances are that increased expenditure will be making a significant impact. If not, …