Foreign aid was increased by 4% over what had been projected last year to bring the 2024-25 aid budget to $4.961 billion, virtually unchanged from the (inflation-adjusted) 2023-24 level of $4.900 billion.

The small increase this year is sustained into the future. In fact, after this year, aid is projected to stay almost exactly unchanged for the next decade and beyond. Over the forward estimates and beyond, the aid/GNI ratio is projected to continue to fall, from the current 0.19% to as low as 0.14% by 2035-36. It is very hard to see in these figures the aid “rebuild” that Labor claims to have embarked on.

Most country allocations are unchanged, but there are a few winners. The share of aid to the Pacific continues its inexorable rise, reaching 44% in this budget, up from 42% in 2023-24 and just 23% a decade earlier. Tuvalu’s aid allocation increases from $17 million in 2023-24 to $87 million in 2024-25 to support implementation of the Australia-Tuvalu treaty. ($87 million is also the amount of Australian aid budgeted for the whole of sub-Saharan Africa in 2023-24.) Fiji gets an additional $35 million for budget support and a port expansion. Indonesia gets an extra $27 million for a climate and energy initiative. There is also $65 million in new funding to support recent commitments to the Green Climate Fund and the Pacific Resilience Facility.

The biggest surprise is in sectoral allocations. Almost a quarter of the aid program went to health during the pandemic, and just below 20% in the last two years. But health spending is slashed in this budget to just 13% of total aid. That’s the second lowest it has been in the last decade, and not what you would expect from a Labor government, especially not one coming out of a pandemic. However, this government has made clear its commitment to governance and infrastructure, and the shares of both increase in this budget. Education and humanitarian spending are somehow protected, leaving health vulnerable, as it was under the Coalition prior to the pandemic.

While there is little else to report from the 2024-25 aid budget, there have been major changes over the last year in the way in which Australian aid effectiveness is conceived of and measured.

Australia’s new international development policy was released in August last year. It promised new country strategies, as well as new strategies on gender, disability and humanitarian aid. About nine months on, none of these has been published. But the first annual report on the “Performance of Australian Development Cooperation 2022-23” has been.

Up until 2020, the Australian aid program measured aid effectiveness by looking at the proportion of investments that were rated as satisfactory every year. Managers rated their own programs, and increasingly thought they were doing well. This indicator kept on improving, reaching 90% or more.

In 2020, a sensible decision was made: to judge aid effectiveness only by reference to the assessment of completed investments, assessments still made by DFAT, but at least not by the implementing manager. These assessments, being more independent, were more reliable, but they also gave much less impressive results, and ones that worsened over time.

In 2023, in the new policy, DFAT decided to hedge its bets and say that it would report both results. The problem with this approach is that it lays bare the large disconnect between ongoing and completed assessments that we highlighted in our report last year. For DFAT itself, this is not a bug but a feature: the completed investments are, it says, judged by a higher standard. The problem with this argument is that the disconnect only starts in 2019 – precisely when these completed investment ratings were taken out of the hands of project managers.

Although the disconnect appears to go down in 2022-23, in fact analysis shows that this is mainly due to the fact that the investments that came to an end last year were generally of above-average quality. The actual gap between the last rating an investment is given by its manager and the rating it is given by external consultants on closing has only fallen slightly.

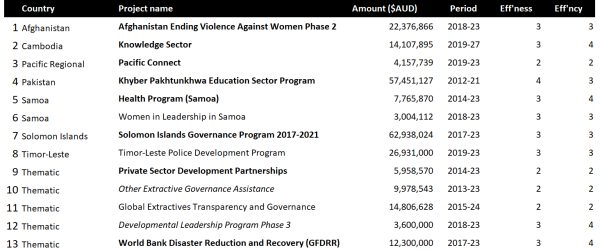

The table below shows the problem at the individual investment level. These are the 13 investments rated in 2022-23 as unsatisfactory at completion. Only three of them were rated unsatisfactory when they had their last managerial or ongoing assessment. Two of them didn’t have such an assessment, and for eight of them, a verdict of satisfactory while ongoing was, on completion, downgraded to one of unsatisfactory.

Table 1: Unsatisfactory aid investments, 2022-23 evaluation period

Note: Bold indicates the investment went from satisfactory in its last ongoing rating to unsatisfactory in its final rating. Plain indicates no change in status from satisfactory to unsatisfactory or vice versa. Italics means no rating in the previous year. The effectiveness and efficiency scores are out of 5 (with 3 or less unsatisfactory). Source: DFAT performance data.

DFAT clearly needs to get an earlier handle on which investments aren’t working well, so that it faces fewer surprises when investments are closed, by which time it is too late to correct non-performance. Until the disconnect is reduced, performance should be judged with reference to completed, not ongoing, investments.

Locally-led development is a major priority for the new aid policy, so it is no surprise that the recently released performance report also has a section on it, with five indicators. Unfortunately, there is no mention of budget support, which is the most obvious and important way in which the Australian aid program supports locally-led development. Budget support is 2022-23 was 9.3% of the total aid budget, the highest it has been for at least a decade.

There is instead a strong focus on the hiring of national staff by managing contractors, who, we are told, hired 3,842 local staff and contractors in 2022-23, an increase of 15%. The benefits of hiring national staff are obvious. (As Lead Economist for the World Bank in India, I benefited from heading a terrific team of Indian economists.) But it’s not locally-led development. Indeed, in fragile states and small countries, hiring national staff can be a form of de-localisation, sucking talent out of local government, non-government organisations and private companies to work for donors at much higher salaries. As these two academics put it, donors can “subvert administrative capacity” when their “presence is large and skilled labour is extremely scarce.”

Data presented in the performance report imply that the average salary for a national staff member is $37,740, which is nine times the PNG minimum wage. Does the Australian aid program have a salary policy to ensure that, where it is a large donor, it is not distorting local labour markets, and thereby undermining localisation?

Other localisation indicators presented are more useful. Managing contractors pass on about 20% of the funding they receive to local organisations. Australian NGOs pass on very little of the development funding they receive, but 36% of their DFAT Australian Humanitarian Partnership funding. Adding these amounts together gives about $290 million, only two-thirds of the value of budget support in 2022-23.

A greater focus on funding local organisations – including governments – and a lesser one on hiring national staff is needed to push the localisation agenda forward.

Devpol’s Australian Aid Tracker has been updated with the new budget numbers.

Listen to the 2024 aid budget analysis episode on our Devpolicy Talks podcast.

Hi Stephen. I agree that the Australian aid has not suddenly dipped in quality. Instead, what we have seen is a steady and concerning fall in the quality of the aid program after almost a decade of cuts and neglect. The clear underlying priority of Australia’s new International Development Policy is to rebuild development capability in DFAT so that an effective and high-quality international development program can be delivered. This prioritisation would not have occurred unless there existed substantive concerns regarding aid effectiveness. Advocating for a larger Australian aid program should be done in a considered way which takes into account these challenges if it is resonate with policy makers and the general public. By promoting the uncontested need for more aid funding the Development Policy Centre also risks being seen as representing just another special interest group where more is always better.

Thanks Stephen, good points made about the performance of the aid program but you leave unanswered the key question as to whether the aid program warrants an increase in real funding when 30-40% of recently completed aid projects fail to achieve their objectives. Perhaps it’s time to change the narrative and recognise that Labor’s capacity “rebuild” of the aid program needs to be given time to work. Only once the effectiveness of the aid program has substantively increased should there be an increase in real funding. By consistently advocating for higher funding levels you seem to be ignoring the performance elephant in the room you have so very well identified.

Hi Neal,

I know what you mean. It is like that quote “The food here is terrible and the portions too small”. That said, there is such a need for more aid, whether we’re thinking about the multiple humanitarian crises the world is facing, the terrible health problems and risks, or the need to massively upscale the global response to climate change. There will always be a mix of successful and unsuccessful aid investments. While the Australian aid program has its problems, from what I’ve seen over my career, Australia is a better donor than many, and I don’t think our aid has suddenly dipped in quality. So I do think advocating for more aid and better aid is the way to go.

Regards, Stephen

I would also just add to this point that if we subjected domestic or defence program spends to remotely similar efficiency and effectiveness standards as those applied to aid spends (let alone actually evaluating the impacts, as advocated by the Assistant Treasurer), the share would likely be far higher and there are few people out there saying we should cut a great deal Australian Government spending until we know for sure it actually works.

I think its also possible to separate the issues in this thread from global norms and aspirations in ODA levels, as it is technically very feasible to increase effectiveness and efficiency with more or less funding very fast. For example, a big increase (or an instead increase in effectiveness with the current quantum) could be plugged to certain multilaterals (e.g., WB) with the absorptive capacity, or large-scale oriented outfits like the Global Fund, GiveDirectly, or any top development charity listed on GiveWell.

Best,

Thanks Stephen

I had to search the Budget papers to find the dollar amounts in our aid budget, especially for any comparison with last year’s. Not surprising to find no virtual increase. I was equally disappointed that the morning media made no mention of our aid – up, down, or steady.

Given the formation and operation of the Australian Centre for Evaluation in Treasury, I was hoping that DFAT would currently assess its effectiveness by the achievement of its intended outcomes. Objectively through independent evaluation- not through comments by the delivering manager, nor by mixing up the data.

I agree with your comments: “Until the disconnect is reduced, performance should be judged with reference to completed, not ongoing, investments.” Though I would add “… with reference to the demonstrable outcomes of completed….”

I noticed too that number one in your table of “Unsatisfactory Aid Investments” was “Afghanistan – Ending Violence Against Women Phase 2” and that the evaluation period was 2018 to 2023. As the source was DFAT performance data, I had hoped than ANY assessment by that Department would have stopped at 20-21.

The next two years cover the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan and their declared and explicit violence against women. It might be my simple visual conclusion, but I remain surprised that any DFAT assessment of its project(s) in Afghanistan could include the years since those dreadful scenes at Kabul Airport in August 2021.

The recent Blog article “Restricted visa pathways for Afghan women” counterpoints DFAT:

https://devpolicy.org/restricted-visa-pathways-for-afghan-women-20240510/

“But any hard-won progress towards equality and human rights for Afghan women, once touted as a substantive moral basis for the war, is being incrementally dismantled by the returned Taliban”.