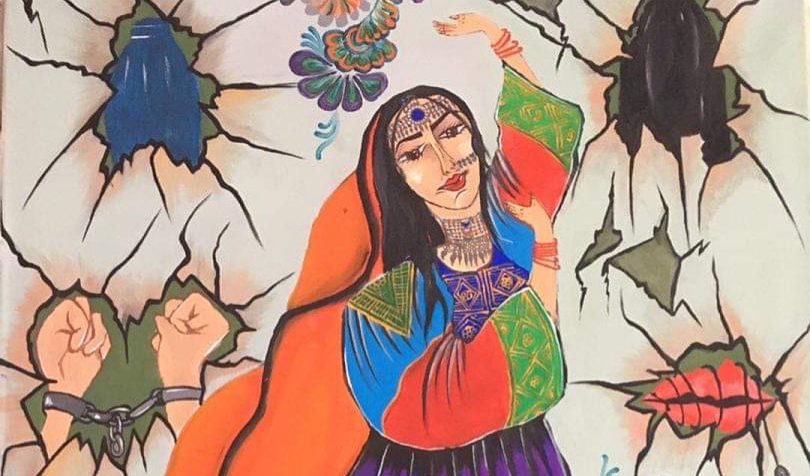

Two decades of conflict and nation-building in Afghanistan have brought both suffering and hope for Afghan women. But any hard-won progress towards equality and human rights for Afghan women, once touted as a substantive moral basis for the war, is being incrementally dismantled by the returned Taliban.

Since 2021, Afghan girls have been barred from schools above year six, women have been banned from most work, and women have faced restrictions on leaving their homes without a “mahram” or male guardian. This year, the Taliban regime has vowed to bring back stoning as a punishment for women who do not adhere to their interpretation of Sharia Law.

The situation in Afghanistan is growing increasingly complex, with restrictions on women continually escalating. People are unable to speak up, and those who dare to speak out face the threat of torture. Many Afghan women fear that, over time, practices like child marriage and the torture and objectification of women may become normalised cultural practices.

A generation of progress and empowerment is now on the cusp of being lost. Afghan women, a pillar of Afghanistan’s potential future, have been trapped behind four walls.

Australia has played a role throughout this process, aiding in the invasion of Afghanistan and subsequent nation-building attempts. While the mission of Western forces was initially to deny terrorists safe haven in Afghanistan, the advancement of women’s rights was often cited as an objective to bolster the mission’s moral legitimacy.

Yet, despite the hardships Afghan women currently endure and Australia’s purported generosity towards Afghans, obtaining a visa to live in Australia is almost impossible for Afghan women. Their most viable route to Australia is via a humanitarian pathway. Australia’s humanitarian program is currently capped at 20,000 places per year. Ostensibly, this is a limit on the capacity of the Australian community to provide permanent settlement for those with a humanitarian need to migrate. However, the exact number of places that have been filled, and how many remain, is uncertain.

One Afghan woman’s refusal decision for a Class XB-200 Refugee Visa states:

I accept the applicants are subject to a degree of persecution or discrimination in their home country and have some connection with Australia. There is no evidence that there is another country available for the applicants’ settlement and protection. The Australian community does not have the capacity to provide for permanent settlement of all applicants such as the applicants at this time.

The document also states that questions about the decision will not be addressed by the Department of Home Affairs, and is not subject to merits review by the Administrative Appeals Tribunal. Responding to the crisis in Afghanistan, the 2022-23 Humanitarian Discussion Paper put forward by the Department of Home Affairs states:

The Department is working to ensure that visa options continue to be available to Afghan nationals, both within Afghanistan and those who have been displaced from their home country. All visa applications will be processed in accordance with Government announcements and within program priorities, and assessed on an individual basis.

However, even a brief examination of these “options” reveals the practical impossibilities faced by Afghan women. For one thing, with restrictions preventing them from leaving their homes or attending university campuses, they are unable to obtain the university transcripts necessary to support applications for student visas.

One Afghan woman, Aziza told us:

Obtaining my academic transcript from the university was an immense challenge. They didn’t allow me to enter the university, and the Ministry of Higher Education banned women from obtaining their transcripts or university degrees. I was not permitted to enter the university, so one of my male family members had to handle the transcript process on my behalf. After many attempts and struggles, my younger brother managed to obtain my transcript, but he couldn’t secure my university graduation certificate. In contrast, my male classmates easily received their diplomas.

Although many Afghan women undertake their university courses in English, Australia requires in-person language proficiency testing and certification through specified service providers, many of which do not operate in Afghanistan. Again, the immobility enforced by the Taliban puts this out of reach. As of July 2023, the only online provider of English language testing, the Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL), is no longer accepted by Australia for visa purposes.

The evidentiary burden for Afghan women is impossibly high, rendering other, non-humanitarian visa options practically unattainable. These systematic, gendered barriers are immoral — but it does not have to be this way.

From the fall of Kabul in August 2021 up to March 2023, Canada welcomed almost 50,000 Afghans across all visa streams. By comparison, between August 2021 and 31 December 2023, Australia granted 4,967 visas, representing around 16,000 Afghans, through the Offshore Humanitarian Program. In the same period, 14,188 visa applications, representing nearly 70,000 Afghans, were refused. Additionally, 29,646 applications (135,114 individuals), are still awaiting a decision. In another comparison, since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Australia has granted over 10,000 visas to Ukrainian nationals.

In 2015, in the midst of the drawdown of Western forces, a group of female Afghan MPs visiting Australia implored the government not to abandon Afghanistan’s women and girls. There are now no women ministers in the unitary Afghan government, nor are women allowed to serve in the judiciary or as lawyers.

This entire situation is devastating. Aziza told us:

I don’t have much hope for the future if this situation continues; all I see is darkness. However, my only hope lies in people standing up against this inhumanity and speaking up for our rights. I want the world to know that these restrictions on women are neither part of our culture nor our religion. It’s an act against humanity and the highest form of gender discrimination. Please stand up with Afghan women and support them in their struggle for their rights.

Last year, former Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard told King’s College London that “failing to listen to local voices to bring about lasting societal change for Afghan women was one of the West’s greatest failures”.

It is a lesson we still have not learned.

These details reveal serious flaws in Australia’s refugee acceptance and visa procession systems. “The evidentiary burden for Afghan women is impossibly high” as the following specific example demonstrates.

Hana* (a pseudonym for her protection) and her 3 girls aged 4, 5, 8 and a boy 9, had lived with her mother, and adult brothers and sister since her husband abandoned them 4 years before the fall of Kabul in August 2021. Her husband had no contact with the family since that time and his whereabouts are unknown.

Australia issued 449 evacuation visas to the entire family except Hana and her children on the grounds they were not dependents. Her adult sister and brothers were evacuated, including her married brother.

Left alone in Afghanistan, Hana* attempted to obtain passports for her children without a male guardian. She was arrested and detained by the Taliban with her children. The Taliban published her children’s names on the grounds they would never be issued with passports as the mother was without a male guardian. They then threatened her and the children for many hours saying she should be shot or forced to marry a Taliban fighter.

Hana* went into extreme hiding as the extended community in Kabul were now aware she was alone with her children. She was extremely afraid someone would recognise one of the children if she sent them out to obtain food.

During this time Australia refused to commence processing of their visa application or to allow health or security checks to be completed for them.

Hana and her children were not able to leave this safe house for over 2 years. She only went outside twice with a paid escort commissioned by an international network, to obtain identification documents for the children and then assistance with evacuation to Pakistan. The Australian authorities did absolutely nothing to assist them.

The policy to refuse visa applications to women left without a mahram is gender biased and has exposed these women to harm for prolonged periods. Pakistan has been forcing back Afghans living there, to the country they fled.

41 of our soldiers died in Afghanistan, protecting its civilians for a better life. In their memory, our policies towards Afghan refugee women need complete reviewing. Facilitating their refugee clearance would be – at last – providing Afghan women with minimal standards of care and protection.

Hallo Isabelle, My name is Sahar Naseri. I am 19 years old and I live in Kabul, Afghanistan.

I lost my family 5 years before. I have one sister. She is 14 years old. I was in the 9th class when Taliban came to Afghanistan. Me and my sister we want to go to school and make our future. Do you know of some possibility how to go in some another country to make our future?

It would be very nice of you how guide us how to apply a visa in a safe country to make our future.

Sahar Naseri