Elections are coming to Solomon Islands. Predictions are never easy in politics but here’s what I think the elections will bring (coupled with my degree of confidence in brackets, ranging from confident to completely confused).

The election will be run fairly well (quite confident)

Recent elections in Solomon Islands have been pretty well run. Not without hitches, but better than those in Papua New Guinea, and better than average for a country of Solomon Islands’ level of economic development. As I’ve explained before, past success has come both from donor assistance and the efforts of local electoral officials. Also, electoral violence is not normalised in Solomon Islands in the way it is in parts of Highlands PNG.

All of these causes of past success are present again in 2019, which bodes well. The only reason I’m not completely confident of a reasonable election is that a recent electoral law change allowed voters to enrol from outside of their electorates. Some candidates took advantage of this change to register paid supporters in constituencies they weren’t from. This may cause problems come election day – both rigged results, and perhaps tensions as locals confront illegitimate voters.

The risk is higher in some places than others. One potentially fraught electorate is Gizo Kolombangara, where a former prime minister is striving to regain his seat. The roll in Gizo Kolombangara is now 65 per cent larger than in 2014 – implausibly large and an obvious concern. In addition to Gizo Kolombangara, there are a small number of other electorates (particularly in Malaita and Honiara) where either roll inflation or local advice points to difficult elections. (Data for all electorates are here.)

The frenetic period of government formation in the elections wake is another possible flash point. New MPs appear to have been strong-armed in the past. Gunshots were fired at a boat that had been transporting MPs after the last election. And when Snyder Rini was announced as prime minister once a government had been formed in 2006, major riots broke out.

Vote buying and voter decisions will be the same as in the last election (confident)

Recent elections have run quite well procedurally in Solomon Islands. But this isn’t to say they’ve been wholly ethical. Vote buying is common. There’s no reason to think this will be different in 2019. There’s no shortage of money. And, although vote buying is illegal, laws only serve as deterrents if they’re enforced. Many strong candidates bought votes in the 2014 elections, but only two MPs lost their seats because of it – hardly a deterrent.

In recent elections, even when they haven’t sold their votes, most Solomon Islands voters have cast their ballots for candidates who they think will help them (or their family or community) directly, through the provision of resources after the election. Voters have not voted on the basis of national policy preferences, nor have they assessed MPs on how well they’ve governed the country as a whole. This is unlikely to change because it’s a perfectly reasonable way to vote in a weak state with no national political movements. (I explain the logic in more depth here.)

About 50 per cent of MPs will lose their seats (completely confused)

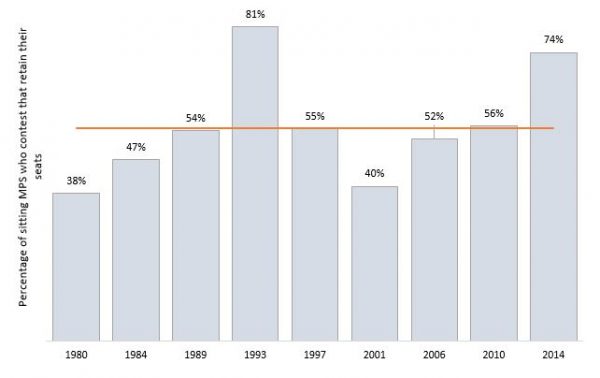

As the chart below shows, incumbent turnover is usually high in elections in Solomon Islands. On average, only about 55 per cent of those sitting MPs who have stood in general elections since independence have retained their seats. It’s tempting to say turnover will be in line with the long-run average. But in 2014, 74 per cent of MPs won their seats back, probably because so-called constituency development funds (government money given to MPs) rose rapidly between 2010 and 2014, giving sitting members an electoral advantage.

Constituency funds are high again in 2019, which would seem to bode well for sitting members. And yet, in the past, voters’ expectations of what MPs can do have adapted over time, meaning there have been elections where many MPs have lost their seats even with slush funds.

Share of MPs winning their seats back

So perhaps there’s no reason to think 2019 will be a good election for sitting MPs. That was my belief until two weeks ago, when candidate numbers were published. In the early 1980s ANU academic David Hegarty noticed that elections with fewer candidates in PNG tended to be elections where incumbents were more likely to be returned. I’ve tested what I call the Hegarty Rule with more recent data and it has generally held true for both PNG and Solomon Islands. According to the latest information from the electoral commission, just 333 candidates registered to stand in the 2019 elections. This is much lower than 2014 (447). If the Hegarty rule holds, 2019 should be a very good year for incumbents.

Will it hold? Possibly not. As Kerryn Baker writes, candidate numbers may be artificially low in 2019 owing to transport disruption caused by Cyclone Oma. Also, registration fees were increased considerably in 2019, and candidates were required to be present in their electorate when nominated. These barriers may have driven out weaker candidates who had no chance of winning, leaving only powerful challengers to contend. If that’s true, the Hegarty Rule might not be a good guide as to whether most sitting MPs will win their seats back or not. Hence my confusion. It may be the case that Solomon Island politics have been changed by money and incumbents are now going to be very hard to beat. Or it may be that come mid-April we will be back to the norm: many new faces in parliament. We will have to wait and see.

Political governance will remain the same (confident)

One thing I’m much more confident of is that, many new faces or few, the nature of parliamentary politics will be the same post-election. People often fixate on personalities in Solomon Islands politics: is person X a reformer? Is person Y corrupt? I understand why. Some MPs have better intentions than others. But at the end of the day, the political incentives facing everyone in parliament are the same. Re-election requires delivering goods directly to supporters and potential supporters back in the constituency. This is more important electorally than governing the country.

And if you’re the prime minister you build your power base by awarding ministries not to the most talented or ethical MPs, but to those MPs who can guarantee votes in parliament. That’s the political logic of staying prime minister. It’s also the political cause of many of Solomon Islands’ governance woes.

One day all of this will change – I’m confident of that. But there’s no reason to think change is coming this election.

If you’re interested in the elections more excellent reading can be found in Transform Aqorau’s DPA In Brief on the elections, Kerryn Baker’s Lowy Interpreter piece on women in the elections, Julien Barbara’s In Brief (with me) on the elections from late last year, and Dan Evans’s recent blog on the political economy of the Rennell oil spill.

Thanks for the blog Terence. Just out of curiosity and of interest – what are your observations on the impacts of CDF generally in the Solomon Islands – what will be its future impacts in the country? And do you think CDF will have a major impact(s) on the outcome of this upcoming National General Election?

Thank you Wilson,

Great questions. Sorry for a short reply, I have to get home to pack to go to Solomon Islands. I think the CDF grew out of a pre-existing need/propensity on behalf of voters to ask MPs for local spending rather than government policy.

When it was first introduced in 1993 the CDF seemed to help MPs a lot (many were re-elected in that election). However, after that MPs started losing elections at a similar rate to prior to the CDF. It seemed as if voters’ expectations had adjusted.

However, in 2014 when the CDF (and other grants to MPs) became particularly large most MPs were re-elected. It will be very interesting to see the impacts of the CDF on this election. It is likely, I think, that the CDF will help sitting members, but not guaranteed.

Some great research is being done on the CDF by people who know more about it than me. Tony Hiriasia is excellent. He has a good paper here: http://dpa.bellschool.anu.edu.au/experts-publications/publications/4381/kin-and-gifts-understanding-kin-based-politics-solomon

Similarly James Batley and Colin Wiltshire are doing excellent work on the CDF.

http://dpa.bellschool.anu.edu.au/experts-publications/publications/4073/constituency-development-funds-solomon-islands-state-play

is one example.

A wonderful read Terence, Just wanted to know your take on the issue of “Devil’s night”, the night before polling where candidates and agents have allegedly garnered more votes by giving money to voters. With the Amended NPEP Act 2018, there will be a 24 hour campaign-free period meaning there should be no devil’s night or atleast that is the intention of that piece of legislation. Do you think this will have any effect on the outcome or results of the elections?

Hi David,

Thanks for your comment. My guess is no effect. Vote buying is already illegal, meaning the behaviour on Devil’s Night is also already illegal. But illegality hasn’t stopped it in the past. So it’s hard to see why it would now.

One reason might be that it might be easier to police the presence of campaign teams in villages buying votes, rather than actual vote buying itself. That sounds plausible. But even then it might just shift Devil’s night one evening earlier.

Short story: I’d be surprised if the new law had much effect in this area. Then again, I am going into this election expecting to be surprised.

Terence

Thanks for the blog Terence. You mention that “one day all of this will change” – what I am most interested in is ‘how’?

Hi Luke,

Good to hear from you. I’ll be in Wellington in early May if you’re about.

The ‘how’ question is the big one, I agree.

In OECD countries patronage politics was put paid to by the rise of social movements which then became political movements. (At least that’s my slightly simplified read of the history.)

Broad political movements can overcome many of the collective action problems which make clientelism otherwise inevitable I think.

So, the rise of such movements would seem a pathway for Solomons. The trouble is (a) not all social movements are positive & (b) it took industrial revolutions to bring such social change to Europe.

Which begs the question, given industrial revolutions aren’t on their way to small island states any time soon, what might have a similar transformative effect? Plausibly, social media? Plausibly new cohorts of the middle class studying together and becoming the building blocks of new social movements? Or plausibly something different. I can’t say for certain. But there is an appetite for change, which is encouraging, hence my final sentence, which I’ll concede is part prediction and part aspiration.

Looking forwards to talking more.

Terence

Constituency Development Funds are a two-edged sword – they can work against against an incumbent who uses them badly or indiscriminately,and challengers can make a great deal of promises.

The micro-politics of each constituency (and polling stations) are very complex and largely hidden from view of outsiders – and thus making electoral prediction inherently difficult.

Always a pleasure reading such clear and concise analysis, Terence.

Thanks Chris and sepo for your kind comments.

Chris, I agree: CDFs are definitely a double edged sword. This is likely why the incumbent turnover rate remained nearly 50% in most of the elections after the CDFs were introduced.

And yet, in 2014 incumbents did remarkably well. Candidate numbers provide some cause to think they will do so again this year (although see caveats in the article). If it turns out CDFs have suddenly become a single-edged sword all of a sudden, the interesting question will be why? (The boring answer might be that they’ve become so large even inept MPs can use them effectively.)

I also agree: outsiders miss the micro-politics most of the time. This is why we’re left using blunt instruments such as candidate numbers (which reflect the micro-politics) when we try and make predictions.

It will be a very interesting election.

Thanks for your comment.

Great read.

Post script: I’ve just received data on candidate party affiliations. People don’t vote along party lines in Solomons, but parties can serve as vehicles of patronage, and loose building blocks of allegiance in parliament.

After the 2010 election, a new law was passed designed to strengthen parties by making it harder to change party affiliations. In the 2014 election this law had the unintended consequence of prompting 31 of the 47 sitting members who contested in that election to stand as independents, so they could have more freedom to switch sides during government formation after the election.

I’m not aware of any subsequent changes to party law since 2014. As such, I was expecting most sitting members to stand as independents again. But this isn’t the case: only 13 of the 48 sitting members contesting their seats are standing as independents this time round. Most sitting MPs are at least nominally affiliated with parties.

The two biggest parties in terms of sitting members are:

SIDP – with 13 sitting members and 22 candidates in total.

Kadere party – with 8 sitting members and 13 candidates in total.

The biggest party in terms of total candidates is the United Party (29 candidates, no sitting members).

I’m still confident that voters won’t start voting along party lines this election. But parties look like they will have more impact on post election negotiations to form government than was the case in 2014.