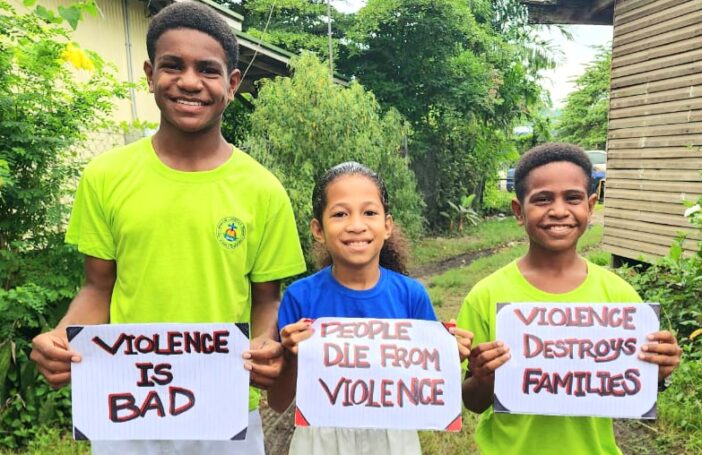

Currently, the 16 Days of Activism Against Gender Violence is taking place around the world. On development blogs, there have been posts on the impact of gender violence on militarism, human security, culture and more, including first person accounts.

Most of this activism has centred on the social costs of gender-based violence (GBV), which encompasses sexual, physical and psychological abuse. These social costs are highly significant, as is the relationship between economic problems and increases in GBV [pdf]. But what are the economic costs? How does gender violence impact on economic development? And is there a way for economic development policies to make proactive gains on eliminating GBV?

A 2004 World Bank report [pdf] provides some insight, as does the latest World Development Report on gender (WDR2012) and this policy brief [pdf] from the Joint Consortium on Gender Based Violence.

From these documents, some of the key economic impacts of GBV are divided as follows:

- Direct costs — these are the costs directly incurred because of domestic violence, including, but not limited to, medical expenses, crisis services, legal services, etc.

- Indirect costs — these costs include impacts on the productivity and earnings of women who are abused, including productivity loss from early death or days out of the workforce due to injury. These can also include the costs (lost productivity, lower tax revenues) incurred from the incarceration of the abuser, as well as some health costs (for example, the need for later-life counselling or support for children who have witnessed violence).

The 2004 Bank report highlights the inadequacies in accounting-based measures of GBV costs, precisely because they fail to consider the non-monetary social costs of such violence. The report advocates for a more comprehensive measure of GBV costs, while acknowledging the difficulty of obtaining full data.

On a micro level, an accounting approach also fails to recognise household or individual costs for women who leave abusive relationships — costs of relocating, replacing personal and family items like cookware or clothing, the cost of losing land or property, costs from potentially being excluded from village or family networks, or the loss of subsistence or market food production from land exclusion.

These national-level cost figures also neglect the significant household shocks that can be caused by even a small shift in productivity in subsistence economies. A relatively small loss of income can have impacts on child nutrition, health and access to education. Additionally, according to the WDR2012, children who witness domestic violence are more likely to perpetrate or experience violence themselves, so there is clearly a cyclical effect at play, which unless addressed, will continue to create constraints for women’s agency and economic development as a whole in the longer-term.

In short, there is significant interplay between the issues associated with domestic violence and economic development, both at the household and national level. However, relatively little has been written on ways that GBV activism can be directly incorporated into economic development programs.

Olufunmilayo I. Fawole [pdf] argues that ‘economic violence’, where an abuser has complete control over a victim’s money and other resources, is a form of gender-based violence in itself — one which is too often ignored. Fawole asserts that economic violence leads to a deepening of poverty and that investing in the primary prevention of economic abuse is a cost-effective measure for governments to take.

Additionally, there has been some examination of the impact of microcredit on women’s exposure to GBV, however the verdict has been mixed. While some microcredit schemes have strengthened women’s ability to stand up to violence, in other cases, access to finance has increased family violence and relationship breakdown [pdf].

The risk of unintended consequences (such as creating resentment towards women or vulnerability through microcredit schemes) needs to be taken into careful consideration in program and policy design. This highlights the importance of gender mainstreaming in agriculture, livelihoods [pdf], governance and finance programs.

Given the high rates of gender-based violence within the Asia-Pacific, which is estimated to be costing the region billions, it is particularly important to integrate GBV reduction messages and strategies into a range of development initiatives in the region.

As we mark these 16 Days of Activism Against Gender Violence, it is a timely reminder that activism needs to go further than awareness campaigns — changes should be implemented through economic, social and development policy and the full costs of violence need to be measured and recognised.

Ashlee Betteridge is a Researcher for the Development Policy Centre.