It is widely acknowledged that “political will” is crucially important for determining the success of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This post examines the political challenges associated with moving from improving access to schooling to providing quality education, a key difference between the education targets of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and SDGs.

But first, some background.

Millennium Development Goal 2, to achieve universal education, only had one target:

To ensure that children universally – including both boys and girls – will be able to complete a full course of primary education by 2015.

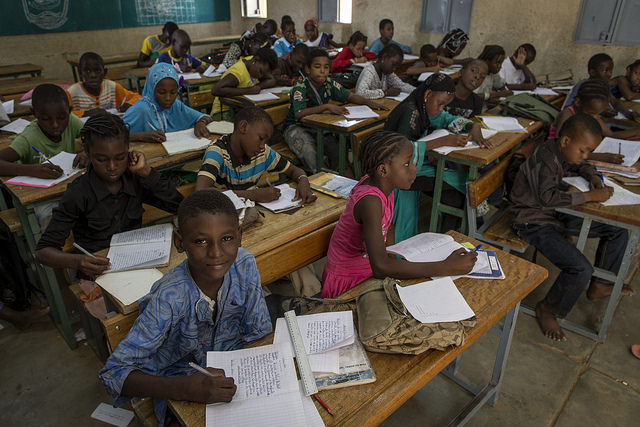

In response to this, resources were mobilised to encourage students to enrol in and attend school. School fees were abolished and cash was transferred to families, often on the condition that their children attended school. The 2015 UNESCO Education for All Global Monitoring report [pdf] notes that most countries now have free tuition policies. Since 2000, in Sub-Saharan Africa, where progress has been particularly impressive, 15 countries have adopted legislation abolishing school fees.

As a result, the MDG Monitor reports that net enrolment – enrolment of the official age-group for a given level of education expressed as a percentage of the corresponding population – in primary education in the developing world improved from 83 per cent in 2000 to 91 per cent in 2015. So, if we believe the underlying data informing these numbers, significant inroads have been made, even though the world fell short of achieving this target.

This improvement is, in part, due to the political buy-in that has occurred across the developing world. In a 2014 article [pdf] in The Journal of Politics, Robin Harding and David Stasavage argue that competition in African elections incentivised governments to abolish school fees. Between 1990 and 2007, 11 Sub-Saharan countries abolished fees immediately after elections. Closer to home, we’ve seen Papua New Guinea’s Prime Minister, Peter O’Neill, introduce a tuition fee free policy shortly after controversially toppling his predecessor Michael Somare in 2011. O’Neill was able to form a strong coalition government after the 2012 election, which was helped by the quick and initially successful roll-out of this policy. O’Neill has made much of his government’s efforts in increasing enrolment numbers.

In the post-2015 world of the SDGs, there is now greater emphasis on improving the quality of schooling. SDG 4 emphasises this shift by calling for ‘inclusive and equitable quality education and promot[ing] lifelong learning opportunities for all’. Quality indicators are embedded within the targets and indicators to achieve this goal. SDG target 4.1 will measure the percentage of children who can achieve minimum proficiency in reading and mathematics. Other targets focus on the quality of the learning environment (target 4a) and teachers (target 4c).

Internationally, there is optimism that SDG 4 will garner significant political support. As opposed to previous attempts to focus on quality schooling, UNESCO argues that it will be easier to secure political commitment for the quality-oriented SDG 4 (see this pdf). This is because, they argue, the SDGs have political buy-in from a broader range of stakeholders, and that they will be better monitored. This may be true at the international level, but recent research suggests that this will not be the case at the national and local scales.

Using Afrobarometer survey data from Kenya, Harding and Stasavage suggest that citizens are likely to vote for politicians who can abolish school fees. However, they are much less likely to vote for those who promise to improve educational quality, because politicians are seen to have much less direct influence over the quality of local schools. They conclude that “there may not be very large electoral rewards for pursing a policy designed to improve school inputs or quality” (2014: 244). This reflects Harding’s recent article in World Politics, which finds that Ghanaian voters hold politicians accountable for road investment but not education quality (measured by education inputs, such as textbooks and school facilities).

Political engagement is not the only factor that shapes school quality: as argued here, the quality of teachers is particularly important for learning outcomes. But securing the resources required to improve school quality – such as well trained teachers – will not happen without political commitment. Given this, citizens’ ambivalence towards political action on school quality does not bode well for SDG 4.

For political will around quality education to emerge at the national and local scales, citizens will need to be convinced that quality education is important (an issue Anthony Swan and I will examine in a forthcoming post on this blog), and that political action can lead to the implementation of policies that actually improve the quality of schooling.

The mechanisms for getting citizens passionate about school quality are determined by context. In some places improving information about school results, finances and benefits of schooling helps civic engagement. From Pakistan [pdf] to the Dominican Republic and Benin, research has found that increasing information can improve test scores and years of schooling. However, others have found that increasing information does not axiomatically result in educational improvements, particularly for the most marginalised. In rural Kenya, Evan Lieberman and colleagues found that improving information about children’s’ performance on literacy and numeracy tests did little to encourage private or collective action on educational quality.

So how can donors shape political commitment towards improving quality schooling within developing countries?

Given the importance of context, research will need to play an important role. In particular, donors could support research that identifies aspects of the education and political systems that impact education quality, and factors that might encourage citizens and others to pressure governments to provide quality education.

Donors can also play a role in improving awareness of the benefits of quality education, through supporting local actors who advocate for improved educational quality, and directly lobbying political elites.

At the national and local levels, securing political support for quality education will be difficult. But this is where international attention needs to be focused if the promises of SDG 4 are to be realised.

Grant Walton is a Research Fellow with the Development Policy Centre.

It’s actually true that politics can only go as far as abolishing school fees and providing resources required for education.

The major challenge especially in Kenya is as much as the enrollment ratio has greatly improved, is the quality of this education also good?

I loved this article.

My favorite part of this article is when you mentioned that all it takes to improve the quality of education is political action. Seeing children suffer from poor quality of education is all over the news so it is imperative to keep yourself updated on what’s happening in the political landscape. After all, knowledge is power, right? If you are an active participant, it will be easier for you to effect a positive change. Thanks for the good read!