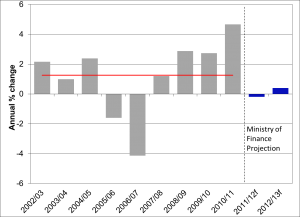

Real economic growth in Tonga has been slow for the past decade, averaging a little over 1 percent per annum (Figure 1). However, the last three years have shown some improvement, with an average of more than 2 percent growth, and with 2010/11 on its own recording 4.7 percent growth. This recent growth has been supported by exceptional amounts of development partners’ assistance, mostly through aid-funded construction, and the associated addition of incomes earned by the foreign-aid construction workers that have been in Tonga for more than 12 months.

While these recent growth figures have been promising, the Ministry of Finance projects that our economy will slow in the foreseeable future as our partner support is expected to wane. In any case, the flow-on effect to the overall population from recent growth has been limited.

Remittances

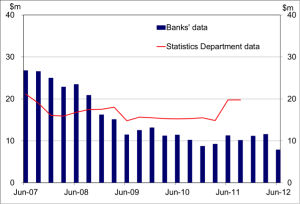

Another reason for Tonga’s bleak economic outlook is an ongoing decline in remittance flows. Remittances have traditionally propped up the Tongan economy, accounting for around 30 percent of GDP in 2008. Since 2008, remittances have fallen by $100 million (Figure 2), equivalent to almost 15 percent of GDP in 2011. This is largely a result of the global financial crisis and its impact upon developed countries, particularly the US, New Zealand and to some extent Australia.

Exchange rates have also had an impact. More than half of our remittances are denominated in USD, and since the Tongan currency (TOP or Pa’anga ) has recently appreciated against the USD, converting USD remittances into Pa’anga now gives us less Pa’anga than it once did.

Exports

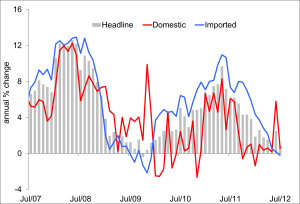

Tonga’s exports have always been small and are also in decline, though different data sources tell different stories (Figure 3). According to the banks’ overseas exchange transactions data, exports declined from 3.5 percent of GDP in 2008 to 1.5 percent in 2011. By contrast, imports are almost 30 percent of GDP. A large part of the fall in exports over recent years is due to the loss of the squash market. Another factor is the deteriorating economic conditions overseas. Short-term export prospects are also limited as natural resources, such as sea cucumber and sandal wood, become less available.

Fortunately, the news on our export market is not all doom and gloom. Tourism is showing potential to support growth in the medium to long term. But in order to maximise the benefits of tourism, related sectors like agriculture and fisheries need to be developed simultaneously to support it and to minimise leakages through imports.

Inflation and foreign reserves

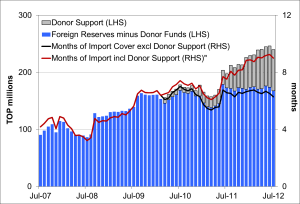

Inflation, heavily dependent on the prices of imports, has declined markedly in recent years (Figure 4). This is a reflection of the downward trend in world oil prices: almost all of our electricity is sourced from diesel generators that run on oil shipped from Singapore.

Our foreign reserves have also increased considerably over the past two years, thanks to development partners’ support (Figure 5). Nearly all capital/project expenditure in Tonga is financed by the support of Tonga’s development partners.

Liquidity and lending

The combination of the National Reserve Bank of Tonga’s (NRBT) recent economic stimulus and generous donor support has allowed liquidity to grow to unusually high levels, with banks’ exchange settlement accounts now sitting at around 15 percent of GDP. So liquidity is certainly not a restraint for economic development.

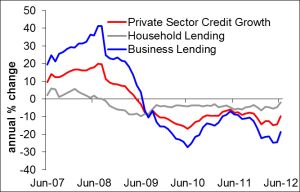

Despite this, lending to both households and businesses has been declining and credit growth remains negative (Figure 6). This can be explained by the high level of non-performing loans (Figure 7): an unusually large number of borrowers went into default from 2008 onwards. Efforts so far by the National Reserve Bank of Tonga (NBRT) and donors have not been enough to outweigh the forces that have been reducing the banks’ appetite to lend, particularly the decline in asset quality.

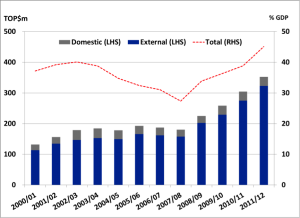

The government has also unfortunately used most of its capacity to stimulate the economy thanks to a record number of expansionary budgets. Given the debt level – approaching 50 percent of GDP (Figure 8) – the government has adopted a ‘no further borrowing’ strategy.

The Economic Dialogue

The NRBT and central government have exhausted their policy tools by progressively easing monetary policy since 2008 and implementing expansionary budgets. Within this context, the NRBT launched a two-day conference in March of this year under the title ‘Economic Dialogue’. Stakeholder discussions and a survey we conducted in the lead up to this highlighted three main areas of concern:

- Lack of market access

- High costs of fuel

- High input costs (other than fuel)

The two day dialogue produced specific strategies and actions to meet these concerns, including the creation of a National Growth Committee to consider the suggested actions, some of which have been put into this year’s budget.

What next for Tonga?

The key challenges facing our economy are:

- Raising actual and potential economic growth

- Reducing public debt when demands on public spending are significant

- Maintaining foreign exchange reserves when donor support wanes

- Building a diverse and dynamic industrial base in the face of declining remittances

- Building and maintaining momentum for economic reforms

On balance, recent economic developments in Tonga have been negative and our economy is in need of a lot of support. If we are to avert a bleak economic future, we need to stop our reliance on private remittances and become more productive.

This is a part of our blog series summarising presentations delivered at the 2012 Pacific Update. The rest of the series can be found here.

Siosi C. Mafi is the Governor of the National Reserve Bank of Tonga. This post is a summary of her presentation (powerpoint available here, video here) to the 2012 Pacific Update.

What follow up has been undertaken by the relevant parties since the Economic Dialogue Meeting? Is it possible for the Reserve Bank or the relevant responsible authorities to let people know what action has been undertaken since the Dialogue meeting.

The excellent presentation by the women led by Robina Nakao and Aloma Johannsen and their team had some specific sensible suggestions. Regular releases on action taken since the meeting would generate some “ownership” of the problems, builld confidence among the wider commnity and stimulate discussions and possible solutions that can be implemented. I am sure that there has been some good work done since the meeting.

Who is on the National Growth Committee, how many times have they met? What have been the results?

There were some interesting challenges to the accuracy of the statistics provided by Government with regards to remittances, value of agricultural exports and tourism earnings which were going to be looked into by the relevant parties. News on the progress made in these areas would be much appreciated.

And if there is a record of themeeting with follow up action points indicating who is responsible for the follow up, this would also be useful

Look forward to receiving any information you may be able to provide.

Stephen Vete

Hala Sipu, Kolomotu’a