The Development Policy Centre has run stakeholder surveys of aid experts in 2013, 2015 and 2018. These surveys provide a detailed picture of how the quality of the Australian Government aid program is perceived by expert aid practitioners. The 2013 Stakeholder Survey established a benchmark. The 2015 Stakeholder Survey delivered a clear set of findings: Australian aid was getting worse. Last night at the 2019 Australasian Aid Conference, we launched and presented the results of the 2018 Stakeholder Survey, which is more complex to interpret, but brings with it a range of important findings.

Stakeholder surveys have two phases. Phase 1 (with 114 respondents in 2018) targets senior staff from Australian NGOs and aid contracting firms. Phase 2 (with 233 respondents in 2018) is open to anyone with a good knowledge of Australian aid. The findings in this blog stem from responses to Phase 1 of the survey. (In 2018, Phase 2 respondents were, on average, marginally more pessimistic in their assessments in most areas. Data from both phases are available online and are covered in the body of the report.)

So what did we find?

Julie Bishop was clearly appreciated by the Australian aid community. She was appraised positively by most stakeholders, and her popularity has increased over time.

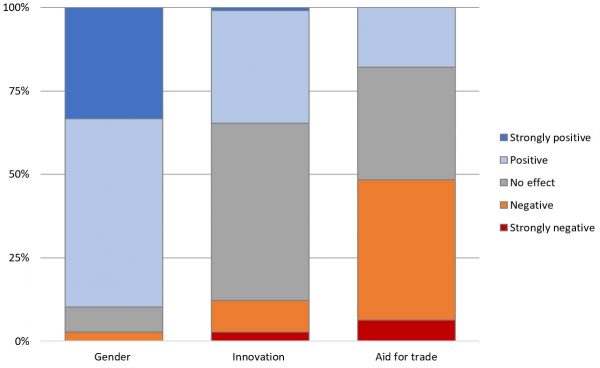

Of the big ideas that Bishop championed or introduced while in charge of the aid program, a focus on women’s empowerment was viewed as beneficial by stakeholders. The rise of an innovation agenda was viewed less positively. And an aid for trade focus was viewed in a negative light by most stakeholders.

Figure 1: Gender, innovation and aid for trade

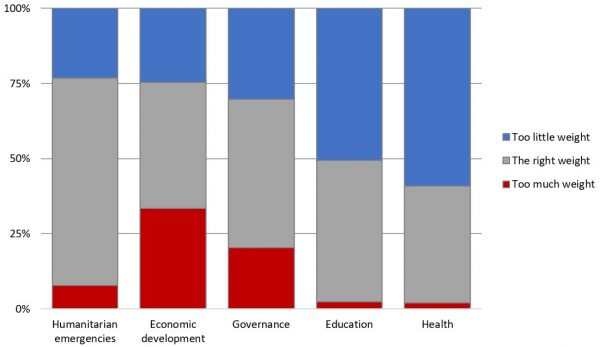

On the sectoral focus of Australian aid, there was a clear concern that too little aid was devoted to health.

Figure 2: View on the sectoral focus of Australian aid

The 2013 integration of AusAID into DFAT was associated with a substantial fall in the extent to which stakeholders thought Australian aid was focused on promoting development. This fall was accompanied by a commensurate rise in the extent to which stakeholders thought Australian aid was focused on advancing Australia’s short-term strategic and commercial interests. The decrease in development focus that occurred between 2013 and 2015 was not reversed in the years between 2015 and 2018. Australian aid is still viewed foremost as being oriented around advancing Australia’s interests.

Figure 2: Perceived objectives of Australian aid (mean response, 1-100)

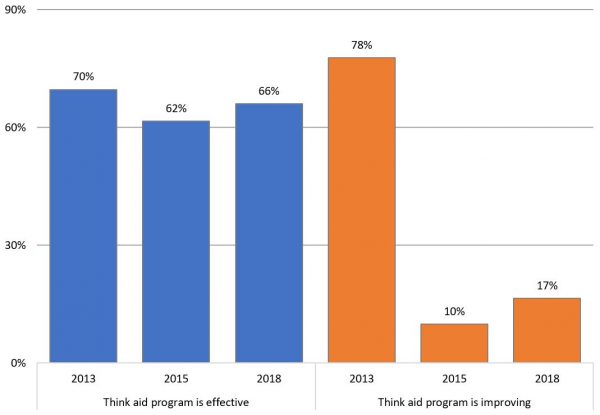

Stakeholders offered a more positive assessment of overall Australian aid effectiveness in 2018 than in 2015. Effectiveness has not returned to 2013 levels, but in 2018 most stakeholders thought the aid program was effective or very effective. However, stakeholders are still, as they were in 2015, pessimistic about the direction of the aid program: a stark contrast to the optimism of 2013.

Figure 3: Views on effectiveness

Stakeholder responses to questions about specific aspects of the aid program in 2018 were more positive than they had been in 2015. Comparisons between 2018 and 2013 were mixed. The greatest improvements have been felt by NGOs, who often have a strongly positive view of the Australian NGO Cooperation Program in particular.

Staff continuity and timely decision making are two specific areas which have improved substantially from 2013 to 2018 according to both NGOs and contractors. However, while DFAT may have become a nimbler aid manager than AusAID was at the peak of the scale up of aid spending, there remains a clear need for further improvement in these areas.

In 2015, we reported that “a loss of expertise is viewed by the sector as a clear cost of the AusAID-DFAT merger.” While staff expertise remains a problem, the sector recognises that DFAT has taken action to remedy the situation.

Although stakeholders see less fragmentation than in 2015, there is no improvement in this dimension relative to 2013, suggesting deeper reforms are needed than simply reducing the number of projects. Funding predictability, transparency, communications and strategic clarity stood out as four attributes that both NGOs and contractors rated much worse in 2018 than they had in 2013.

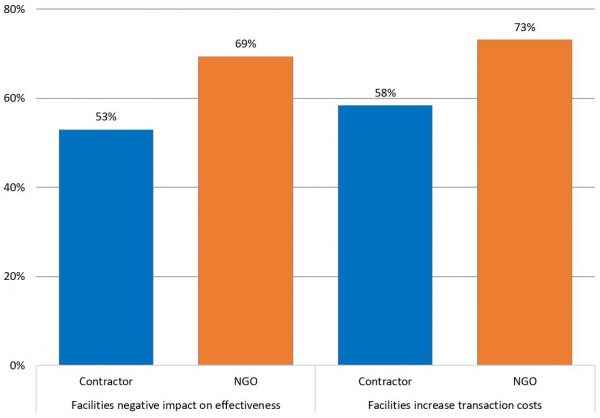

New issues have arisen since the last stakeholder survey. The rise of facilities – large contractor-managed entities comprising many aid projects – is the most notable of these. How important facilities have become is indicated by the fact that slightly more than 40 per cent of survey respondents were funded or managed through a facility.

A majority of respondents think that facilities are reducing the effectiveness of Australian aid. A bigger majority thinks that they are adding to transaction costs.

Figure 4: Views on facilities

Overall, to summarise, the 2018 survey shows a rebound in aid quality since 2015, but not to the levels found in the 2013 survey, which was carried out just prior to the current government taking responsibility for the aid program.

On aid quantity there was in 2018, as in 2015, a very clear break between what almost all stakeholders wanted – aid to rise substantially as a share of GNI – and what they thought they would get. However, stakeholders were somewhat more optimistic about the prospects for aid increases should Labor form the next government.

These findings lead to a series of recommendations:

Focus aid on development. Absent a development focus, aid is less likely to help those in need. Promoting development also brings benefits to Australia.

Review and reform facilities. Facilities can add value in certain situations, but at present they are often failing to do so. Reform is needed.

Continue to build on improvements in staff continuity and staff expertise. While significant gains have occurred, much needs to be done. Staff continuity is assessed as the second worst of all the individual attributes, and staff expertise the fifth worst.

Similarly, prioritise improving aid program transparency and communications – areas where performance continues to lag. Transparency should be made one of the official benchmarks by which quality of aid is assessed.

Maintain the gender focus of the aid program, ensure that innovation in aid is properly scrutinised and drop the 20 per cent aid for trade focus. A preoccupation with innovation and aid for trade simply distracts from the important task of carefully tailoring aid to needs and focusing aid on what is actually likely to work.

Our final recommendation is for the broader Australian aid community, which needs to grow its advocacy capacity and resourcing if it is to ever to reverse the cuts Australian aid has suffered over the last decade.

Not long after this report is released, Australians will go to the polls. The government that emerges from the elections, regardless of its political stripes, will have plenty of scope to promote positive change in Australian aid if that is its desire.

We plan to survey stakeholders again in three years’ time to gather views on what has changed – for better or for worse – in Australian aid.

Leave a Comment