While there is uncertainty about PNG’s population count, there is no doubt that since the arrival of the first missionaries in 1847, Christianity has become an integral part of life for the majority of Papua New Guineans. There is also no doubt about the important role of the churches in delivering health services across PNG. A Devpolicy blog on Australia’s aid budget for PNG in April 2022 noted that church health services administer close to half of the health facilities in rural areas.

While there is uncertainty about PNG’s population count, there is no doubt that since the arrival of the first missionaries in 1847, Christianity has become an integral part of life for the majority of Papua New Guineans. There is also no doubt about the important role of the churches in delivering health services across PNG. A Devpolicy blog on Australia’s aid budget for PNG in April 2022 noted that church health services administer close to half of the health facilities in rural areas.

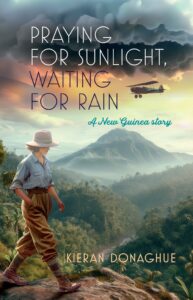

Kieran Donaghue’s novel, Praying for Sunlight, Waiting for Rain: a New Guinea Story, is a compelling story about a young Lutheran missionary couple in the central highlands of New Guinea from 1933 to 1943. A former AusAID officer, Donaghue made a number of visits to PNG in the course of his career. Before joining AusAID, Donaghue studied philosophy in Australia, the US and Germany in the 1970s and 1980s. He has brought this interest and experience in the big existential questions of philosophy and development – in particular, the nature of belief and the concept of progress – to this finely executed work of fiction.

When asked why he chose to write a novel set in the New Guinea highlands in the 1930s, Donaghue responded that his interest arose first through his visits to the highlands as an AusAID officer and second through reading Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel: A Short History of Everybody for the Last 13,000 Years (1997). Diamond referred to the PNG highlands as “one of the small number of sites worldwide where settled agriculture arose indigenously” (p. 303). Donaghue further expanded that it was not until the 1930s that:

Europeans first discovered that a large indigenous population with settled agriculture lived in mountainous country that had previously been considered too wild and rugged for habitation. For the Germans, Australians and Americans who entered the highlands from 1933 – as searchers after gold, as explorers seeking new places to chart and new peoples to study, as missionaries competing for souls, or as patrol officers looking to impose their government’s view of law and order – this region was one of the earth’s last frontiers.

While there is considerable historical literature on the early contact between Europeans and highlanders, the range of fiction set in PNG is limited. Donaghue felt there was room for a new fictional account. It has memorable characters and dialogue, a well crafted and compelling story, and vivid descriptions of the remarkable landscape of the highlands – its mountains, valleys, rivers, flora and fauna. The novel is also grounded in solid historical research. It provides a chronology of New Guinea from 1844 to 1944, a background chapter on historical sources and a bibliography.

Set mostly in the Wahgi Valley, about halfway between Mount Hagen and Goroka, the main protagonist Ellen is a young woman from Adelaide, South Australia. She marries Carl, who has been called to serve as a pastor in the Lutheran mission in the newly discovered PNG highlands. Although Ellen believes in God and is supportive of Carl’s work, Ellen is not an evangelist. She is in love with her husband and approaches her new life with a sense of intellectual curiosity and discovery.

Carl is a complex character. He tells Ellen that “unlike his colleagues, he was searching for a form of Christianity that would sink deep roots into highland culture, remaking it from within”. Carl sees “mastery of the language” as key to understanding the local culture and aims to “think in the local language” (p. 152). In his quest to understand highland culture, concerns are raised with Ellen that Carl is taking part in local rituals, taking sides in clan disputes, taking unnecessary risks, and seeking to locate highland culture on the scale of civilisation: “perhaps Carl wants to know more than is necessary, more than is even possible for an outsider” (p. 130).

The legacy of Carl’s German father is palpable. His father had set off into the South Australian desert seeking converts among Aboriginal people and translated the New Testament into an Aboriginal language. Carl acknowledges that:

… the missions to the Aborigines might be considered a failure. Perhaps his father had come to think of them as such. But he had nonetheless contributed much to the stock of knowledge about native languages and beliefs, knowledge that would be of great benefit to those who wished to lift up the blacks (p. 46).

Ellen concludes that Carl’s father had persisted “in an impossible task” which had imposed “enormous costs on his family and himself” (p. 51). Ellen has justifiable fears that Carl is following in his father’s footsteps. These fears are realised when Carl disappears in mysterious circumstances and is presumed to have died. There is also the possibility that Carl has fathered a child with a local woman.

Through Ellen and Carl, we are introduced to a rich cast of characters including Lutheran and Catholic missionaries and their local staff, Australian patrol officers (kiaps) and administrators, villagers and local evangelists, Australian gold prospectors, labour recruiters and pilots, and Japanese soldiers. Donaghue uses these characters to offer multiple perspectives on questions of belief and progress. Themes explored include the competition for souls between different missionary groups, tensions between the missionaries and the Australian administrators, Canberra’s penny-pinching policy towards its mandated territory, the suspicion with which the Lutherans were viewed in the lead up to World War II and the unexpected speed and impact of the Japanese invasion in 1942.

Another dimension of the novel is its depiction of the people and culture of the highlands. Ellen has completed training in basic nursing in Adelaide which enables her to offer basic medicines and advice on hygiene and sanitation to the local villagers, with some success. Shocked by the suicide of a young woman given in marriage to an older man who had multiple wives, as her relationship and confidence with the village women develops, she encourages mothers to delay giving their daughters in marriage and to increase the time between pregnancies. She makes efforts to learn the local language and teaches the village children to read and write, using a dictionary of the Wahgi language compiled by Carl. Toward the end of the novel, Ellen surprises herself by defending the highlanders to a group of Catholic nuns, saying “their invention of settled agriculture showed what they were capable of” (p. 307).

Donaghue makes good use of local characters who act as intermediaries for Carl and Ellen in their quest to better understand the culture. Sorcery is identified as the biggest cause of harm and barrier to progress. The novel succeeds in conveying the complexity of life for the highlanders – the complicated web of clan and sub-clan allegiances and obligations, the subjugation of women, the toll of preventable diseases and the “longstanding feuds and recent quarrels, almost impenetrable to an outsider” (p. 141).

The novel could be characterised in a number of ways but, at its heart, it is about Ellen’s odyssey from being a relative ingénue to achieving maturity in this environment. She develops a deeper understanding and knowledge of people and place, and she experiences love, grief, loss and war. Her fate at the end of the novel is unclear but we hope she will be able to fulfill her dream of returning to the Wahgi Valley to continue her work to improve the lives of the local women and girls.

I have read Kieran’s book too and really enjoyed it. I have been to PNG many times myself, so was struck by how well Kieran can paint a vivid image of a PNG scene in just a few words. As just one example, he writes about the character Ellen going towards a local building that he describes as: “a building of native materials on stilts standing over pieces of lawn and beds of bright flowers edged with white stones”. Great image.