This is the final blog presenting the findings of a research project exploring the impact of family and sexual violence (FSV) on families and children. Previous blogs have looked at services to address FSV in Lae, the impact on families, and the impact on school attendance. This post presents our findings on the relationship between the women in our study and the police, including the reasons they did or did not seek police help. This is important in light of the focus over the past decade on the police and criminal justice system in responding to family violence, as reflected in the enactment of the Family Protection Act 2013 and the rollout of specialist Family Sexual Violence Units (FSVU) in many police stations.

Overall, the emerging findings of our study, detailed below, suggest caution with regard to the adoption of policies such as mandatory arrests, or “no-drop” policies, that remove agency from the survivors and may push them even further from the system that is ostensibly established to support them.

Women navigate between informal and formal support mechanisms

Although there are valid reasons to object to binary distinctions between formal and informal justice systems, given the hybridity that characterises much of PNG, we use the terms ‘formal’ and ‘informal’ to reflect how the different mechanisms are conceived by our 71 interviewees. The main informal community mechanism available to women are the ‘blok komitis’ (see here and here), an ubiquitous feature of local governance in PNG’s urban settlement communities. ‘Blok komitis’ can be problematic for women seeking to address FSV and IPV for a number of reasons. For instance, they charge ‘table fees’ which many women cannot afford, and the outcomes often involve compensation payments, the terms and prices of which are set at the discretion of the komiti. They are also often based on local ethnic or social groupings, so members of the komiti may be kin to the perpetrator. Moreover, as seen elsewhere in PNG’s urban settlement communities, komitis may privilege collective social harmony over a need for justice for the woman seeking support. Yet, as we discuss below, this local mechanism for resolving conflict – witnessed by local community members – can be effective for longer-term resolution.

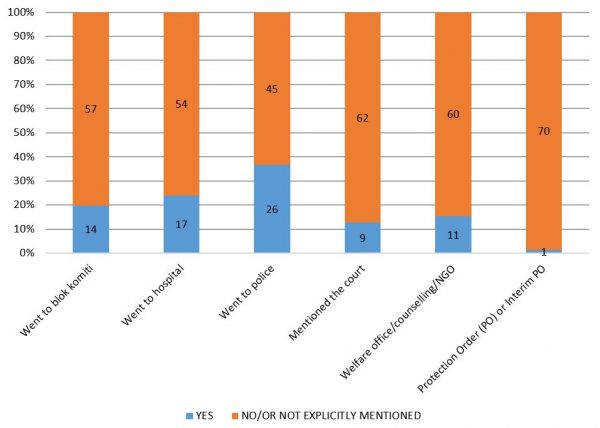

As can be seen in Figure 1, the women we interviewed mentioned various support mechanisms, sometimes accessing more than one mechanism. The single largest source of support mentioned by the women was the police. The ways in which women navigated across the different support mechanisms will be presented in a forthcoming discussion paper.

Figure 1 – What support mechanisms did women mention in interviews and did they seek support from these? (N=71)

A range of barriers prevented women from seeking support from the police

Women who did not seek support from the police faced a range of barriers in so doing. For some, social norms mean FSV and IPV are not viewed as a police matter. For others, the police did not feature in their experiences. For example, one woman shared her experience of childhood sexual abuse. However, for most women, the greatest barriers included the fear of the violence worsening, worry about the costs, or a lack of confidence in the police or formal system. Costs included worry about losing financial support from their partner, transport costs, perceived ‘fees’ charged by the police, and the income opportunity cost of time spent going to the police. Some typical responses we received when we asked about why they did not go to the police were: He threatened me; I was scared; Who will look after my children?; Who will pay the school fees?; I did not have time and was scared of losing income; They might put him in jail and how will I get him out again?; I can’t afford the police fees.

Many women want help, and know the police are there, but they are confronted by the fact that the laws, police, and the formal system can only be accessed once the women themselves overcome the formidable barriers between themselves and the law. As one woman noted: ‘See the law will tell me that if I hold his hand and lead him here [to the law] then we [the law] can help you. But if you are just watching and thinking about doing something then we [the law] cannot help you.’

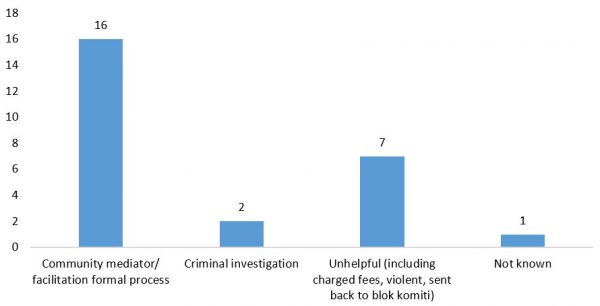

When women did seek police support, they usually received it, with police mostly triaging support by referring them to various pathways in the formal system. In most cases, the police also provided a mediating role between the woman, her partner and, if needed, other parties (see Figure 2). This mediation support generally involved the police responding to prevent further violence. The importance of this mediation role was reflected in the consistent references to a variety of terms referring to a ‘polis pepa’ (police paper). The ‘polis pepa’ reflects the way Lae police use the police complaint form by giving it to complainants to deliver to the perpetrator to request him or her to come into the station for mediation or a police interview. In general, women did not complain about this mediating approach being used instead of the strict criminal justice response of charge, arrest and prosecution (which we were only told about in two cases). However, some women reported disappointment with the process, explaining: He did not turn up when the police told him to; He ran away; The police felt sorry and let him out of the cell; He threw the paper away.

Figure 2 – Types of responses women received from the police (N = 26)

From the perspective of the police, using the complaint form in this way has a number of advantages. It is a discrete way for the police to approach a perpetrator (via the complainant), in contrast to arriving at the home and causing fear among family members. It is readily available and can be issued outside the station. It allows the victim to exercise control over the decisionmaking process, while providing an initial record of the complaint. It enables the woman to navigate her lived reality between the formal police and court processes and the community ‘komiti’, leaders and family members. For example, if a woman seeks to resolve her FSV problem through the common practice in PNG of seeking a compensation payment from her husband for the violence inflicted on her, she may be advised by the police that they are unable to mediate compensation payments. If she insists on pursuing compensation, they refer her back to the community leaders for mediation. If she faces problems at the community level, she can return to the police with the complaint form as an initial record.

Overall, these findings refute the arguments made by some commentators that police simply “dismiss their plight as minor misdemeanours.” However, they also show that the police need to improve their strategy in ramping up their response where more conciliatory approaches have been tried and failed, are unwanted by the survivors, or are unsafe. Such a sequenced response needs to be made clear to the survivors and their perpetrators, and enforced often enough that it is a credible threat. This requires a responsive approach that respects the agency of survivors in a way that ideally would build their trust in the system, whilst maintaining the positive benefits of the existing relational approaches. In this, it stands in distinction to rigid policies in other jurisdictions such as those of “no-drop” and mandatory sentencing.

Conclusions

Our research demonstrates that in response to FSV, women navigate through various informal and formal support mechanisms. Moreover, as noted in an earlier blog, many women experiencing IPV remain in the relationship for economic reasons. The data here suggests that women, including women who experience IPV, also face difficulties in seeking support through both formal and informal mechanisms.

To seek support, especially from the police, they need to muster considerable fortitude to bring a perpetrator into the formal system, and then draw on financial and personal resources to navigate through the complex web of documentary, institutional and other factors this entails.

This data suggests three interrelated areas for improvement:

- Help women overcome the barriers to seeking support.

- Strengthen, streamline and simplify the community-facing end of police support and all the legal and support pathways that matter most.

- Develop a structured but responsive police approach to family violence that combines the benefits of the mediating aspects of police responses with the formal powers of the criminal justice system, with a focus always on women’s agency and safety.

Finally, most of the women came to the interviews because they wanted to share their stories to help others, to be heard, or because they were desperately asking how they could end the violence. The responses to this research in themselves are a resounding call for investments in counselling in all public-facing parts of services.

Leave a Comment