In April 2018, as part of a research project into family and sexual violence (FSV), we interviewed women from a range of communities in Lae, PNG’s second largest city. In this blog, we share some insights from the stories we heard relating to the financial pressures women face because of violence, and the impact of that violence on families and the next generation(s). Financial hardship is widespread, and impacts both on women’s ability to access justice services, and also upon their ability to leave violent relationships and still support themselves and educate their children.

Violence and financial hardship

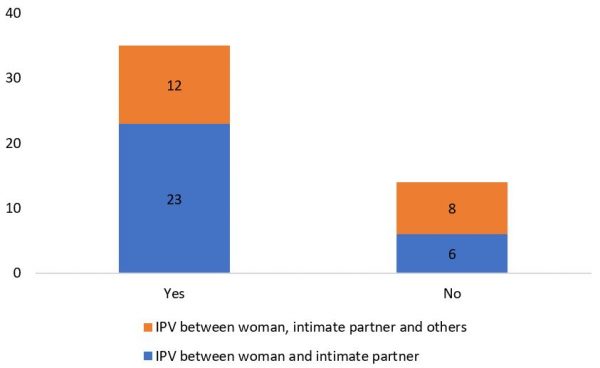

49 of the 71 women who came to see us (55 from informal settlements, 15 from formal residential areas, and one from a rural area) were the victims of intimate partner violence (IPV) (Figure 1). For 20 of these 49 women, their experience of IPV also involved other people, such as the husband’s other partner. In 16 cases, the perpetrator was not an intimate partner but another family member, such as a son. Most women (36 out of 49) experiencing IPV remained in the abusive relationship (the orange bar), and indeed many expressed a determination to continue in the relationship.

Figure 1: Participants experiencing or who have experienced FSV (N=71)

With or without violence, most of the women we interviewed live precarious lives. They had low educational backgrounds, earned low incomes, and worked in the informal sector. 42 per cent earned less than K100 a fortnight. 60 per cent worked on a tebol maket (table market) or haus maket (house market), the common references to small market stalls, selling goods outdoors near their homes.

Of the 49 women who suffered violence at the hands of their intimate partner, including IPV that involved other people, 71 per cent related experiences about how violence led to financial hardship (Figure 2). Financial hardship was common for women still involved in abusive relationships, and even more so for those who were separated.

Figure 2: Experience of IPV involving financial hardship (N=49)

As can be seen in Figure 3, 39 per cent of the women who remained in relationships with IPV earned personal incomes below K100 per fortnight. Many of these women were financially dependent on their husbands and were reluctant to leave or even report the violence because of concerns for their children and family livelihoods. In contrast, most of the 13 women who were no longer in the relationship had been abandoned by their partner for another woman, leaving them in severe financial hardship and often dependent on family for support. Over half (54 per cent) of these women who were no longer in the relationship with their intimate partner earned less than K100 per fortnight (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Income of women experiencing IPV (N=49)

Some husbands left without any information about where they were going and did not stay in touch with their family. Some men had had multiple affairs or entered into polygamous relationships, living with their family but being very violent towards the mother and children. Other husbands came home drunk and woke up the whole family, chasing them out of the house. Most children were left with their mothers when their fathers left for other women. In many of these cases, the man also stopped supporting their family financially. Hardly anyone who had separated from her partner was able to obtain maintenance from him to support their children.

Resilience and social support

We found many resilient women who, despite their experiences of violence, still created avenues to support their family. Many of them sold buai (betel nut), cigarettes, biscuits and other items they could access, usually making just enough to support their family, while the men contributed little or nothing at all.

The community and neighbours are reluctant to assist couples or people involved in FSV, which in many ways contributes to the escalation of violence, as an earlier resolution would usually lead to less violence, especially to women. Many women said that neighbours hardly ever intervene to stop physical violence between a couple because of the perception that domestic violence is a family matter that must not be interfered with by anyone outside of the family or the household. On the other hand, insiders do play a role. Both family members and other non-family members within the same household often stop or control violence among family members.

Friends and relatives do provide support for families experiencing FSV. Although they are unlikely to intervene to try to stop the violence, friends – especially other women – and relatives do assist women and children in need. Sometimes they step in by taking care of children when the parents are unavailable.

For many women who remained in abusive relationships, many said they believe in God and trust Him to take care of them and their children. They expressed their reliance on God to help them solve violence in their family or with dealing with their partner.

Most women staying in relationships involving IPV also sought support from a number of avenues including the local mediating committees, the hospital, and the police. The police were the main avenue for seeking support, and in a subsequent post we will discuss some issues involved in seeking police support.

FSV and boys

We will talk more in the next blog about the impact of FSV on school attendance. But there were clear impacts of FSV on the behaviour of boys in particular. Women told stories about how their sons resorted to drugs, homebrew, excessive alcohol consumption, pick-pocketing and other unlawful activities. Children who are involved in this type of activity are disadvantaged and can become trapped.

Some women also spoke about violence and verbal abuse from sons when there is no food or money. Their sons expect their mothers to provide for them. These youths spend most of their time taking drugs or drinking alcohol before returning home. Women in this scenario suffer from the double effect of FSV – from their partners first, then from their children, especially sons. Continuous and cumulative occurrences of violence, especially from abusive fathers, lead to children developing negative perceptions on schooling and turning to anti-social behaviours.

At the same time, women also recounted stories of their sons being important sources of support by entering into income-earning activities, such as collecting bottles to sell or going to the market to sell betel nut, from an early age. As they got older, some sons also intervened to stop their fathers from beating their mothers.

Conclusion

Most women who experience FSV suffer financially as a result. Most women who experience FSV nevertheless stay with their partner, in part for financial reasons, and in part for reasons of faith. We will discuss some of the challenges and experiences in seeking formal or informal support in a forthcoming blog. Neighbours and family members provide some level of support in relation to FSV, but this tended to be limited to care in crisis moments, rather than intervening to prevent harm from occurring.

Our research also suggests that family violence creates cycles of crime, violence and drug abuse, both in the short term (with some boys abusing their mothers) and possibly in the long term (with those boys going on to abuse their future partners). Boys may end up involved in criminal activity to earn an income, and may also abuse their mothers for being unable to support them. FSV services need to include mechanisms to better accommodate and disrupt the cycle of financial abuse and hardship faced as a result of violence.

A previous blog on services to address family and sexual violence in Lae can be found here. Part three of this post, on how FSV affects school attendance, can be found here, and part three, on police responses, here.

I very interest and I have a question for you,

I want to ask you a question, Me I have a problem I can called you and make a appointment.

An excellent study, I am interested to know how we ( Tree Kangaroo Conservation Program) can partner with your organisation in order to get this program into the rural villages of YUS LLG in Kabum district ( Morobe Province) where the program has worked in for over the past 21 years, and FSV, seems to be on an increase and I would very much be interested to meet up with you, to further discuss further opportunities in terms of partnership and networking with you all.

Thanks,

Thank you Francisca. We will be returning to Lae this year to share the research findings with stakeholders through a workshop. This may be an opportunity for you to attend and meet other stakeholders in Lae and Morobe. It would also be great to hear more about your work. My email is michelle.rooney@anu.edu.au. Please feel free to contact me to follow up on the timing of the workshop.

A very good study which needs to be extended to the rural settings as well.

Very interesting study. How can you support replication in other towns/ provinces ? And support and enable local organisations to undertake the research and participate in the analysis?