This post summarises a recent working paper on the future of agriculture in the Pacific islands, prepared by Wesley Morgan for Asia and the Pacific Policy Studies.

In January 2014 the Australian Minister for Foreign Affairs, Julie Bishop, announced Australian aid would be re-focussed towards near neighbours in the Asia-Pacific region. She also announced that ‘aid-for-trade’ would form a key strategy for improving living standards. While much could be done to help Pacific island states take advantage of international trade, it is important that support is directed where it is needed. Aid must help to develop supply side capacity and address market access issues. Australia also needs to review quarantine restrictions which stymie potential Pacific exports.

‘Hidden strength’ of Pacific economies

Agriculture is easily the most important economic sector for the Pacific island countries – providing the greatest source of livelihoods, cash-employment and food security for more than eight million people across the region. Typically, food production dominates the sector – with ‘village-level’ farmers growing and distributing a large quantity and varied range of fresh vegetables, root crops, nuts, fruits and flowers. Because many of these farmers focus on growing food for their own families, or to share with others through socially-embedded systems of exchange, traditional food production is often under-represented in national accounts and has been identified as a ‘hidden strength’ of Pacific economies.

Development policy should build on this hidden strength. A key challenge is to find ways to commercialise traditional systems of farming and improve cash-generating opportunities, without sacrificing community cohesion and local food security. Other sectors – particularly tourism and mining – are important in some Pacific countries, but these are unlikely to provide the volume of job opportunities required to meet the needs of growing island populations. Thus the focus of policy for employment and for economic growth should be on promoting opportunities in agriculture.

Islands of opportunity: new incomes from high value crops

For much of the 20th century commercial agriculture in the Pacific was dominated by large-scale colonial plantations geared toward the export of bulk commodities – especially copra, coffee, cocoa and sugar. Over recent decades, however, the smallholder sector has been fastest growing, particularly in Melanesia. The sector has also proved to be remarkably price-sensitive, with many farmers choosing what to grow based on the vagaries of international markets.

Smallholders in the Pacific are unlikely to compete either on price or volume with low-cost, high-volume producers in South-East Asia. Island growers face inherent cost disadvantages. ‘Village-level’ production involves small economies of scale, input costs are high, natural disasters are common and transport between islands is often expensive and/or infrequent. In short, growers need to receive considerable returns to compensate for these unavoidable costs.

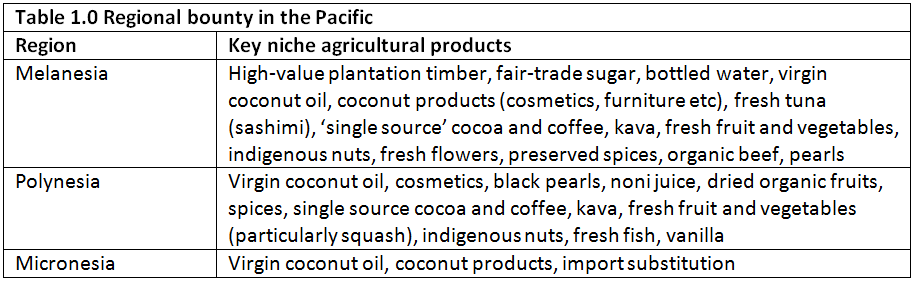

To take advantage of international trade in the 21st century, smallholder producers in the Pacific will need to focus on high-value, low-volume exports. Thankfully, opportunities abound, and island producers already export a range of high-value agricultural products to markets across the globe (see Table 1 below). Furthermore, many of these exports complement traditional systems of food production without supplanting them. Thus Pacific smallholders are growing food around and underneath high-value crops destined for export. Crops like sandalwood (and other high-value timbers), noni trees, indigenous nuts or kava are all suitable for inter-cropping in smallholder food gardens and village plantations.

Marketing key to improved returns

The flip-side of the high costs associated with island agricultural production is that many places in the Pacific are inherently marketable. Remote and ‘exotic’ locations, warm and happy people, and ‘clean and green’ production fire the imagination of would-be consumers. Sophisticated marketing strategies which use the Pacific ‘brand’ to stand out from the crowd are one way of targeting discerning buyers who are prepared to pay more for island produce – a price premium that is vital to offset high costs of production. An example of successful marketing for a niche product is that of Fiji Water, which has become a drink-of-choice in Hollywood and has even been seen wetting the lips of US President Obama. Indeed in some years Fiji Water alone has accounted for up to 20% of all Fiji’s exports.

Another way to stand out from the crowd, and to improve returns to growers, is through fair trade or organic certification. Here, consumers are prepared to pay a price premium for Pacific produce if they know products are good for the environment and for people. In recent years sales of fair-trade labeled products have increased dramatically in Australia and New Zealand (particularly for coffee and chocolate). In rural Papua New Guinea, more than 10,000 people currently benefit from community projects funded by improved returns for fair trade coffee. In Samoa hundreds of farms are certified as organic, and a women’s business organisation sources organic coconut oil for a multinational cosmetics retailer.

Both fair-trade and organic certification can be an expensive process, requiring regular assessment by external auditors, and costs can outweigh returns to growers. Improved returns require farmers working together to absorb these costs. In 2011, 4000 members of a Fijian sugarcane growers’ cooperative started receiving a ‘fair trade premium’ from British sugar-company Tate and Lyle – which now retails the sugar with a Fairtrade label. Another way to minimise certification costs is to develop Pacific-appropriate standards. In 2008 a regional ‘Pacific Organic Standard’ was endorsed by regional Ministers of Agriculture and an ‘Organic Pasifika’ labelling system has been developed. The next steps are to develop guarantee systems for organic produce and to seek ‘equivalency’ for organic standards in potential export markets.

Quarantine restrictions are a major barrier

Developing export pathways is key to growing Pacific agriculture. It’s no good harvesting high-value papaya or ginger or cut-flowers if there is no way to get produce to consumers who are prepared to pay top dollar for them. A key challenge is transport – is there any way to get to market? But perhaps an even bigger issue is market entry. Quarantine restrictions have been identified as the weakest link in the Pacific’s horticultural export marketing chain. Here the Australian government could do much to help speed up quarantine assessments for island produce. Michael Finau-Brown, who heads a cooperative of growers in Fiji, argues that at the current rate of assessment it would take two lifetimes for Australian quarantine agencies to approve for import the full range of fruits and vegetables Fijian growers are now ready to supply to Australian consumers.

Australia’s 2011 aid review found that quarantine restrictions should be based on firm science and should not place undue restrictions on agricultural exports from neighbouring countries. Nonetheless there is little doubt that Australian policymakers maintain restrictions that keep out more price-competitive Pacific island produce. Ginger exports from Fiji are a case in point. Fijian biosecurity authorities made a formal market access request for fresh ginger in 2003. A decade later the Australian Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries completed a risk analysis which found ginger imports from Fiji should be permitted subject to specified phytosanitary measures. However, Australian farmers successfully lobbied for a Senate inquiry into ‘the effect on Australian ginger growers of importing fresh ginger from Fiji’. While that inquiry remains ongoing, fresh ginger exports to Australia remain on hold.

Regional cooperation is vital

Australia and New Zealand are currently negotiating a regional trade agreement with 14 Pacific island countries (PACER-Plus). Money earmarked as ‘aid-for-trade’ often goes to helping Pacific governments engage in international trade negotiations. However, if PACER-Plus simply requires island countries to restate, or sign on to, rights and obligations similar to those included in the World Trade Organisation’s Agreement on Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) Measures, it will do little to expand agricultural trade. Aid-for-trade funds allocated to lengthy negotiations, for agreements of doubtful benefit, could be put to better use developing supply-side capacity and addressing market access barriers in a more direct way.

This is not to say all existing aid-for-trade is misdirected. Current donor-funded projects in the Pacific do aim to resolve quarantine issues, improve trade related infrastructure, provide information regarding international market opportunities, improve production techniques, maintain quality of supply, and develop new marketing and branding initiatives. Many of these aid-for-trade projects are subject to short-term funding cycles, and much could be done to coordinate support to would-be agricultural exporters on an ongoing basis. However, the good news is that there is significant potential for the export of high value crops and improving exports will reap widespread benefits for decades to come.

Wesley Morgan is a Research Associate at the Development Policy Centre.

Thank you for this commentary Wesley. Mostly, I agree with your assertions but make some disagreement with the particular Quarantine case that you bring to light and would like to join you in highlighting that capacity needs to be built on the developing country side to address some of these issues.

Firstly, as a plant pathologist with a particular interest in plant biosecurity I believe it is important to realise that not all injunctions brought against an Import Risk Analysis are solely to protect an industry without any scientific basis, which I hope is not implied here. I’m not saying that it doesn’t happen, but I think a soil-grown crop which could easily be transferred from market to garden is not the best example to use. Soil-borne pathogens are particularly difficult to control and manage for. I note that Tess mentions above that New Zealand allows in many more imports, but they also lack the environmental and cropping diversity that we have here in Australia. In some cases I believe that any potential contaminants would be restricted in spreading in a country such as New Zealand just through hostile climatic conditions. As I don’t know the full details of the case I feel uncomfortable commenting too much further – suffice to say that I would like to see a little more agricultural technical expertise taken into account when making broad-sweeping policy recommendations of this sort. Ginger may also not be a good example when you are also (and I fervently agree with you here) recommending that smallholders focus on differentiated products that command premium prices (as also recommended in the reference of Ron Duncan).

Difficulties with slow IRAs could be addressed in part through a committed long-term capacity building effort in areas of plant pathology, entomology and agronomy which would allow for countries such as Fiji to have the intellectual and technical capacity to address the speed of such applications on their own side, while having the added bonus of helping to reduce pre- and post-harvest losses to pests and disease before they leave the farm gate and hopefully improving farmer incomes. “Low technology” skills in these areas are still sorely lacking in developed countries and sustained commitments from funding agencies (be they sovereign nations or NGOs) could begin to address these issues. Similar commitments to succession planning and adequate and appropriate staffing of Australian agencies may also go a long way to dealing with the backlog of IRAs that need addressing.

You’ve not mentioned the opportunities at home, although Tess alludes to them (I’d note that Carnival is procuring bottled water from Vanuatu and is negotiating on other commodities including coffee and chocolate). Far simpler and more cost effective than exporting agricultural product would be to supply to existing industries, particualrly the tourism industry. However, the quality of produce and regularity of supply invariably means that hotel chains import from Australia. This is a domestic issue to address, and clearly a challenging one – years of aid-funded agricultural strengthening programs don’t seem to have had a significant impact on the quality or consistency of supply.

Aid for trade isn’t, and shouldn’t be, just about exports. More can be done to ensure that there is no need for imports from Australia and New Zealand where domestic production is possible – we need to satisfactorily meet demand at home before focusing too strongly on highly competitive and cost-sensitive export markets.

Thank you Linda. I am wholly in agreement more can be done to link smallholder agriculture with the tourism sector in Pacific island countries – particularly in Fiji, Vanuatu, Samoa and the Solomon Islands. I note that a fair bit of work is going on in Fiji at the moment trying to link vegetable growers in the Sigatoka Valley with hotels on the Coral Coast and elsewhere. This work is supported by the Pacific Agribusiness Research for Development Initiative (PARDI).

Wesley, thank you for the blog and supporting paper. You’ve comprehensively captured both the challenges and opportunities for agriculture in the Pacific and its fundamental role in the livelihoods of people throughout the region. Developing export pathways for agricultural (including forestry and fisheries) products and addressing the associated quarantine requirements has indeed been a long standing challenge and source of frustration for the region’s public and private sector. In recognition of this, the Australian Government began supporting the Pacific Horticultural and Agricultural Market Access (PHAMA) program in 2011 to provide technical support and build the capacity of countries in the Pacific region to gain and maintain market access of high value primary products. The program specifically works with both the public and private sectors in target countries to address the regulatory aspects of biosecurity, quarantine and research and development related to market access for high priority fresh and processed primary products. Countries currently targeted within the program are Fiji, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga and Vanuatu. The program also provides specific resources to the Australian Department of Agriculture to increase their capacity to progress requests from the Pacific region for new or improved market access and to the Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC) to provide support for biosecurity related market access issues at the regional level.

The point raised on the need for greater cooperation between the public and private sector to prioritise market access issues is an important one and real progress is starting to be made. A key component of the PHAMA program has been the establishment of Market Access Working Groups in each of the target countries to provide a practical working partnership between government and the private sector to manage the resolution of market access issues that are to be addressed through the program. These working groups are at different stages of evolution and consideration is now being made on the options for continuation of their functions and mechanism when the current phase of the PHAMA program ends in June 2017.

It is also positive to note that the case study you provided on the request by the Government of Fiji for access for fresh ginger into Australia has been progressing in recent months following technical negotiations between the biosecurity authorities of Fiji and Australia.

An issue perhaps not fully explored in your paper is the need to increase awareness of the existing market opportunities for agricultural products from the Pacific region and how they can be better utilised. For example, improving awareness of what products can be exported already or with some form of processing; increasing the compliance of products with biosecurity or quality standards; or improving the quality or market niche of products.

The work being supported by PHAMA is strongly complemented by the broader efforts being made by the public and private sector in partner countries, through other donor programs and the increasing focus of the Australian Department of Agriculture and New Zealand Ministry for Primary Industry on the region. A real reminder that efforts at one part of the export supply chain can only lead to success if the steps before and after also being addressed in a coordinated way.

BRONWYN WISEMAN is Deputy Team Leader on the PHAMA program, which is managed by URS and Kalang on behalf of the Australian government.

Thank you Bronwyn. I think the PHAMA program is a good example of regional cooperation to help producers in island states take advantage of potential commercial opportunities. I note with interest the development of national ‘Market Access Working Groups’. I think the philosophy behind them is sound; as a mechanism allowing the domestic private sector to drive market access priorities, and as a means of stimulating a working relationship between growers and government. I look forward to reading further on the Working Groups.

It seems to me that the work of the Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC) “to provide support for biosecurity related market access issues at the regional level” is a regional public good that should be supported on an ongoing basis. On the face of it, pooling the highly specialised expertise needed to help island states maintain compliance with quarantine measures in destination markets (in areas such as entomology and plant pathology for example) makes a lot of sense.

Thanks for this Wesley, and also for your paper which I enjoyed reading very much – it’s great to be able to expand this conversation. I agree entirely with all that you have said about export potential and blockages arising from Australian quarantine and phyto-sanitary issues. These are less of an impediment (by a very significant margin) when it comes to exporting agri-prducts (e.g. root crops) to New Zealand from the Pacific.

Your paper references the work of PT&I in this space and they have certainly done some sterling work with producers, including assistance with labelling, barcodes, etc. This is reflective of the need to work with the entirety of supply chains.

I think there are a couple of points to add in relation to supplying domestic markets (see also the forthcoming ‘Pacific Conversation’ with Astrid Boulekone). In countries such as Vanuatu there is more to be done about linking primary producers with the tourism sector. (I won’t bore you again with the ‘why tourism is like mining’ argument). In all Melanesian countries, urban populations are growing and for reasons of economy and public health (nutrition) there are increasingly strong arguments for ensuring that foodstuffs can move from rural to urban locations and be affordable to people who are not able to produce for themselves because they do not have access to a garden or they do not have time to grow food because they are participating in the wage economy (or a combination of the two).

To return to the current ‘steer’ for the Australian aid program, there have been several mentions of leveraging private sector (and in particular Australian private sector) actors as development partners. Carnival (owner and operator of P&O cruise ships) has been cited as an exemplary ‘development partner’ (by people other than me). I hope we can see this partnership being ‘leveraged’ so that Carnival becomes an active (and indeed proactive) purchaser of niche products such as those you have identified here. Their track record in this space is extremely disappointing so there is plenty of opportunity to improve and impress.