On October 27, Devpolicy hosted a discussion on the World Bank and the ADB based on the recent Oxfam and Manna Gum report Banking on Aid. In this blog, Rob Jauncey of the World Bank’s Sydney Office provides a response.

The World Bank Group and Australia are becoming increasingly close partners in successful global efforts to reduce poverty. Responding to a clear interest in more information about the World Bank, including in recent posts on this blog, this note is intended to provide an overview of achievements to date in reducing poverty, some lessons learned from experience, the role the World Bank has played in international development efforts, and some thoughts about how Australia and the World Bank are working together.

Successes in Reducing Poverty

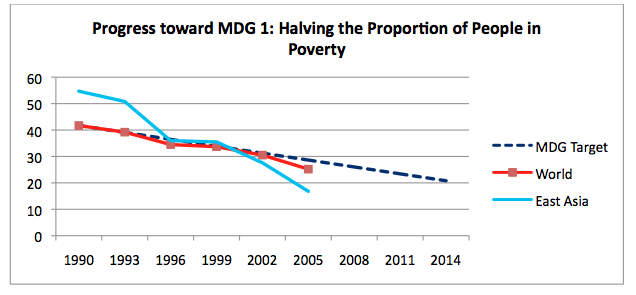

The past 20 to 30 years have seen unprecedented gains in the fight against poverty. Most noticeably, the world is on track to meet the key millennium development goal of halving poverty between 1990 and 2015. At a time when the world’s population has increased from 4.5 to 6 billion people, the number of people living in poverty has fallen from 1.8 billion to 1.3 billion currently – a decline from 40% to 25% of the total population.

Of course, tremendous challenges remain, with over a billion people globally still in absolute poverty. Progress has been uneven between countries. Stronger growth has often been accompanied by economic volatility. And while there has been real progress on improving key social indicators, such as increasing the number of girls and boys in school, and reducing preventable deaths of mothers and babies during childbirth, much more is still needed. But these challenges have to been seen in the context of the very real successes that have been achieved.

Lessons from Experience

One of the key lessons from the past two decades is that those countries that have moved ahead had leadership who adopted policies to help their people: they opened-up their economies; made room for the private sector, encouraged investment, built strong institutions, strengthened the rule of law, and placed a high value on improving critical services like health and education.

The world has changed dramatically in the space of a generation. Rather than old distinctions between the “first” and “third” worlds, we are now in a multi-polar economy, with developing countries increasingly the drivers of global growth. We have seen this with the remarkable growth of East Asia as those countries liberalized their economies and invested in education, as well as more recently in India as that country has opened its economy, and even in the growth now emerging in parts of Africa.

To say that nothing works in reducing poverty like good policies is not ideology. It is statement of fact – an “evidence based” observation to use the current jargon. One illustration of this is the clear link between policy performance and better outcomes. This is illustrated in the comparisons below between growth and child mortality outcomes and policy performance – as measured by the Bank’s country policy and institutional assessment ranking which measures performance on a whole range of indicators from economic and debt management, to gender issues, to environmental management [i].

The World Bank’s Efforts in Reducing Poverty

Primary responsibility for the gains that have been made in reducing the number of people in poverty rest with the countries and people that have led the economic transformation that we continue to witness.

While conscious that correlation does not mean causality, however, I’d also suggest that as the world’s largest non-profit organisation committed to poverty alleviation, the World Bank can plausibly claim to have made at least a modest contribution to these outcomes. Unlike a commercial bank, our bottom line is not profit but the difference we make in people’s lives. Over the last decade the International Development Association – the World Bank’s fund for the poorest has provided almost 50 million people with access to a basic package of health, nutrition or population services; and supported immunization of more than 310 million children. These are not idle figures, but ones we can back up with research that can be made available for scrutiny.

The World Bank is committed to giving more resources to countries with a large number of poor which are showing the leadership to help themselves. We know that aid is more likely to be effective in countries like Bhutan, Cape Verde or Samoa (the highest scoring IDA countries in the Bank’s 2010 performance rankings) than in Chad, Angola, Burma or Zimbabwe.

Still, we also recognize that a one size fits all approach is not appropriate. While the broad outlines of what works – encouraging private entrepreneurialism, investing in people, respect for the rule of law – is clear, a single detailed policy template is not appropriate for the Bank’s smallest member (Tuvalu) as for our largest (China). I frankly don’t recognize the World Bank described as a doctrinaire policeman of a “neoliberal” philosophy. Criticism that a poor country cannot borrow from the Bank without a water privatization strategy [ii] is nonsense. I have worked directly on over 12 countries for the Bank…and the only one in which water was a key part of our dialogue was when we were encouraging Macedonia to think carefully before privatizing hydropower assets precisely because of the potential impacts on broader water resource issues. In my experience, it has been far more likely for the Bank to suspect investments or programs because countries have not show a commitment to core safeguard policies – such as respect for indigenous people, the environment, proper resettlement – than over disagreements on economic policy issues.

Australia and the World Bank

Australia is an important partner for the World Bank. This collaboration is in the interests not just of Australia and the Bank, but is a relationship that is good for development and good for poor people around the world. Working with the World Bank offers a range of opportunities for Australia, particularly as the Government increases aid. The Bank has proven ourselves to be one of the most effective aid delivery mechanisms. Partnering with the Bank offers Australia opportunities to draw on our country expertise and knowledge to scale up in priority regions such as Africa, where Australia does not have as strong historical or economic links.

Even in Australia’s neighbourhood, World Bank engagement in countries of South East Asia or the Pacific can support Australia’s own efforts to encourage to growth, poverty reduction and policy reform. In response to urging and support from Australia, for instance, the Bank has significantly scaled up its engagement in the Pacific islands, providing not just finance but expertise. Among other successes, this has led to real gains in the region, such as telecoms liberalization which has seen mobile phone usage rates increase from 7% to about 70% of the population – with over a million new people in far flung Pacific islands now having access to telecoms services in less than five years.

Of course, there will also be some things that Australia can better do bilaterally. This is not an either/ or question. It is an issue of balance and the best instrument to meet specific objectives. The same is true of the debate over earmarked versus core funding. On one hand earmarked funds offer very specific control over a small area, while core funding gives Australia the opportunity to influence and have a greater voice within the organisation.

A Commitment to Transparency

While I’m proud of what the World Bank has managed to achieve, none of us are perfect. Scrutiny helps us to improve further and we’re committed to engaging in an open discussion on issues. There is an old phrase that “sunlight is the best disinfectant” – and in this sense the World Bank is committed to practicing what we preach. The World Bank ranked the highest-performing donor among 30 major donors in a 2010 study on aid transparency by U.K.-based Publish What You Fund, a coalition of civil society organizations working on governance, aid effectiveness, and access to information. Similarly, the Bank has and will continue to recognise the role and responsibility of divergent stakeholders. We have provided a larger voice for developing countries, including an additional Board seat for Sub-Saharan Africa and increased the voting power of developing countries to 47% (reflecting their current proportion of the global economy) with a view to 50% over time.

So where to for the World Bank over the next twenty years? I hope and expect that we’ll continue to change to reflect an evolving world. We have, and will continue to reform in response to both the internal and external environment. Despite the enormous gains made in the fight against poverty, addressing the needs of what Paul Collier has termed the “bottom billion” remains a critical moral and economic imperative. All of us involved in reducing poverty – governments, civil society organisations, multilaterals, the private sector, academia – have a role to play. In my view, working together in a spirit of collaboration, will ensure the efforts of the whole will be greater than the sum of its parts. The challenge is big enough that we’ll need to pull together if we’re to succeed.

Notes

[i] While child mortality is used as a proxy for MDG outcomes, a similar correlation can be seen for policy performance and almost all other social indicators.

[ii] See, for instance, “Banking on Aid” (Cornford 2011), repeating claims by the Bretton Woods Project.

Robert Jauncey is the senior country officer in the World Bank’s Pacific, PNG and Timor Leste department, based in Sydney. The views expressed here are his own.

Leave a Comment