The United States: the world’s biggest economy, most powerful country, and the richest too, well one of them anyway. It’s a state of the world we’ve got very used to, but it’s something which is changing fast.

The emerging economies of Asia are becoming very large indeed but they are still poor. China is now the world’s second largest economy, and by 2020 is projected to knock the US off its perch. So it is big, becoming bigger, but it is not yet rich. It is much less poor than it used to be, but compared to the US or Australia China is still a poor country today, and it will be by 2020 and even 2030.

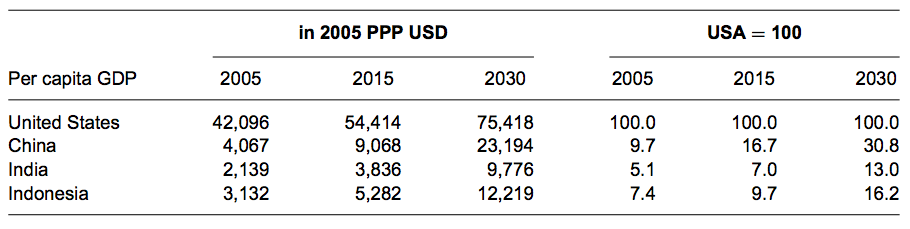

The simplest measure of this is per capita income. Here are some projections I developed a couple of years ago in an article with Ross Garnaut, Frank Jotzo and Peter Sheehan. In 2005, per capita income in China was just 10% of that in the US. By 2015, China’s per capita income is projected to be less than 20% of the USA’s, and even by 2030, only 30%. India and Indonesia are significantly poorer still. (This table uses purchasing power parities (PPPs) to compare incomes rather than market exchange rates. This corrects for the lower cost of living in poorer countries. If market exchange rates are used, poor countries appear even poorer.)

Historical and projected GDP per capita for the US, China, India and Indonesia

Per capita income is a pretty abstract concept. There are some far more concrete indicators of the enduring poverty of Asia. One is how people cook their food. In developed countries like Australia it goes without saying that just about everyone uses modern energy to cook, electricity or gas. Of course we do. But not in Asia. In Indonesia, almost 120 million – more than half of the population – cook on wood, charcoal or dung. And even in powerhouse China, about 700 million – again more than half the population – cook either using these traditional sources or using coal. Think of the inconvenience of cooking using one of these fuels. Think of the health risks: an estimated 420,000 die in China every year as a result of indoor air pollution.

Weaning households off reliance on traditional energy and into the modern energy sector is a central part of the development journey. It’s a milestone we passed by a long time ago; but one that developing Asia is still grappling with today, and will be for decades to come.

Why does this distinction between size and wealth matter? Because the failure to make it is causing all sorts of confusion. Strategic analyst Hugh White in his recent critique of the Australian aid review claimed that “Indonesia is richer than Australia.” Bigger, yes, but richer, no. Australia is up close to the US numbers in the table above; in a different league altogether from Indonesia when it comes to per capita income. But Indonesia is about ten times our size, and so has a bigger economy. The distinction is important. It would obviously make no sense for Australia to give Indonesia aid if the latter was richer. The fact that it is merely bigger is relevant to understanding the importance of aid, and for defining an appropriate aid strategy, but is much less relevant to the case for aid per se.

Many of the debates around climate change and China rest on the same confusion. China is the world’s biggest emitter, but it is not a ‘rich’ emitter. Its per capita emissions are a fraction of ours (between a third and a quarter). We all need to act on climate change, but rich countries need to lead. And only if we recognize that China is still a poor country can we accept that action for Australia should mean a reduction in our absolute level of emissions while action for China should mean slower growth in its emissions.

Clearly, size matters. But so too does wealth. And we will tie ourselves up in knots if we don’t distinguish between the two. China, India and Indonesia now number among the world’s largest economies, but they are not yet developed economies. Yes, they have a large middle class, not to mention a staggeringly rich elite. But overall they are still poor, and they will be for decades to come. The link between wealth and economic and strategic power has been broken.

References:

The per capita income projections table above is taken from R. Garnaut, S. Howes, F. Jotzo and P. Sheehan (2008) ‘Emissions in the Platinum Age: the implications of rapid development for climate change mitigation’, Oxford Review of Economic Policy 24(2): 1–25

For the energy poverty statistics, see the report I recently co-authored for the World Bank with Leo Dobes, Climate Change and Fiscal Policy: a report for APEC.

Leave a Comment