At the very end of last year – two years, two months and nine days after the World Health Organization announced the start of the pandemic – Tokelau recorded its first-ever case of COVID-19. It was the last place in the Pacific to report infection and the second-last place in the world, behind Turkmenistan which still dubiously claims to be COVID-free.

Tokelau is a non-self-governing New Zealand territory that can only be reached by a 24-hour boat trip from Samoa. The territory required all visitors boarding the boat to be fully vaccinated and return a negative RAT within 24 hours of travel, and since announcing the first case has imposed an inter-atoll travel ban to prevent the spread of the virus.

Isolation, capacity for border controls, and political dependence are factors that Tokelau shares with other Pacific territories. In a recent article, I explore the experience of COVID-19 in the six Pacific territories (Guam, American Samoa, Pitcairn, Tokelau, French Polynesia and New Caledonia) listed by the United Nations Special Committee on Decolonization, with the additional inclusion of the French overseas collectivity of Wallis and Futuna.

The Pacific territories had avoided the impacts of relatively recent past epidemics, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and had no pandemic health emergency preparedness. Border closures were crucial amid this initial uncertainty, allowing time for the spread of information and the development of strategies for management. Distance from the relevant metropolitan political power – who had their own immediate priorities – made effective early responses difficult.

The quick closure of borders delayed the arrival of the virus in Pitcairn, Tokelau, and Wallis and Futuna for longer than the territories which never definitively closed their borders, and continued to allow repatriation and other flights, cargo shipping and the occasional fishing vessel. Guam was constitutionally unable to close its borders and control migration from the United States: it experienced a high mortality rate after COVID-19 spread from passengers on a United Airlines flight. French Polynesia had similar problems because of its extensive transport linkages with metropolitan France (with the virus arriving via an infected politician returning from Paris).

As the virus spread, territories adopted the same practices and strategies of quarantining, isolation, mask wearing, social distancing, hand washing and sanitising as elsewhere. Vaccination was strongly recommended, and especially appropriate in small islands, such as Tokelau and Pitcairn, where social distancing is culturally and geographically difficult. Contact tracing was ineffective everywhere. Levels of vaccine hesitancy and complacency ranged across the territories resulting in variable vaccination rates, and opposition to compulsory vaccination and other pandemic policies was seen in New Caledonia and French Polynesia.

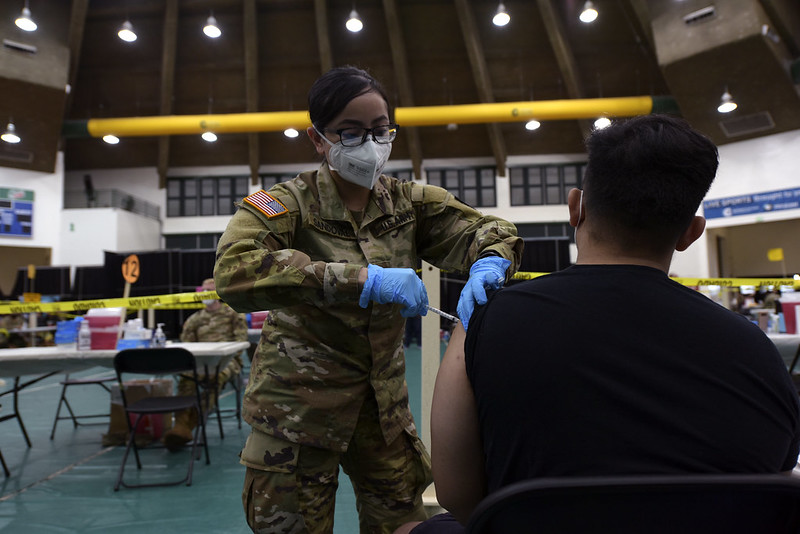

The territories broadly welcomed the assistance of the metropolitan authorities in providing physical and human (and moral) support. The US sent Department of Defense health workers to Guam, along with technology (such as high-flow oxygen for acute respiratory failure) otherwise unavailable there. France sent health workers to New Caledonia and to French Polynesia.

But tensions with metropolitan powers also occurred. In Wallis and Futuna, disagreements reignited debates about the dependence of the territory on both New Caledonia and France, the dependence of Futuna on Wallis, and the role of Polynesian customary authorities in decision-making. In New Caledonia, frustration over the uneven ethnic distribution of the victims, and disproportionate Kanak deaths, was an underlying source of tension. Kanaks consistently argued for stronger borders than France was willing to implement. In French Polynesia, protests against compulsory vaccination were used to demand sovereignty for the territory and to express opposition to plans by France to explore or mine the seabed.

COVID-19 had a massive economic impact on the economies of the territories which are dependent on tourism. The collapse of tourism immediately following border closures saw incomes and employment collapse. Beyond tourism, economic activity in the territories is of more limited significance and was much less affected by the pandemic. Military expenditure declined only little in Guam and its support of the economy remained. Since a significant proportion of employment in several territories is in the public service (exclusively so in Pitcairn and Tokelau, and almost as much in Wallis and Futuna) – and mainly supported externally through the metropolitan powers – employment levels did not decline as they did in neighbouring independent states. Mining continued in New Caledonia.

Limited transport and communications, however, hampered both pandemic responses and development. Delays and restrictions imposed by other countries weakened and disrupted supply chains – always a problem in isolated territories – and reduced access to and increased the cost of goods of various kinds. Even Guam was affected. Outer islands in both American Samoa and French Polynesia suffered from fractured domestic transport systems. Tokelau experienced reduced maritime contact with Samoa that slowed the flow of goods and building materials – the intended construction of a first airstrip was delayed.

COVID-19 exposed weaknesses in health, economic and social systems worldwide. The Pacific Island territories were no different – but risks, impacts and outcomes varied between them according, in large part, to when and how securely borders were closed, but also according to geography, budgets, demography and economic sectors (notably tourism). No territory was unaffected.

Responses to the pandemic in the Pacific territories had a distinctly political sense, reinforcing divisions of geography and ethnicity, reflecting history and even the memory and practices of past epidemics. Indigenous populations, already relatively disadvantaged, were disadvantaged further – but in New Caledonia Kanaks used COVID-19 to strengthen their claim to independence.

The pandemic resulted in territories, or groups within them, both simultaneously distancing themselves from the metropolitan power and deepening their dependency on its expertise, technology and finance, but always uneasily striving to balance and benefit from the best of both worlds.

This blog is based on an article in the Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies journal, ‘COVID-19 in the Pacific territories: Isolation, borders and the complexities of governance’, by John Connell.