Introduced in 2012, PNG’s Tuition Fee Free (TFF) policy is one of the few government initiatives that has shown significant signs of success – especially during its initial roll out. More recently, questions have been asked about whether the policy is unravelling, as accusations of mismanagement and unnecessary policy changes emerge. In this post we draw on our recent pilot fieldwork in Central Province to show how changes to the TFF policy are being received by district administrations, school management and communities.

One of the key features of the TFF policy was that subsidies were sent directly to school accounts, bypassing provincial and district administrations. For example, when the policy began each primary school allocated 270 kina per student, and schools could decide on what it should be spent on. They could directly access this funding once their budgets had been approved by subnational administrators. This was a significant shift towards devolving the management of funds to the school level.

The PNG National Research Institute and Development Policy Centre’s A Lost Decade? report found that most primary schools were receiving TFF subsidy payments, and school administrators and the community had more say in how they were spent (although few had received monitoring visits). Since then, there have been attempts to reduce the say that schools have over how subsidies are spent.

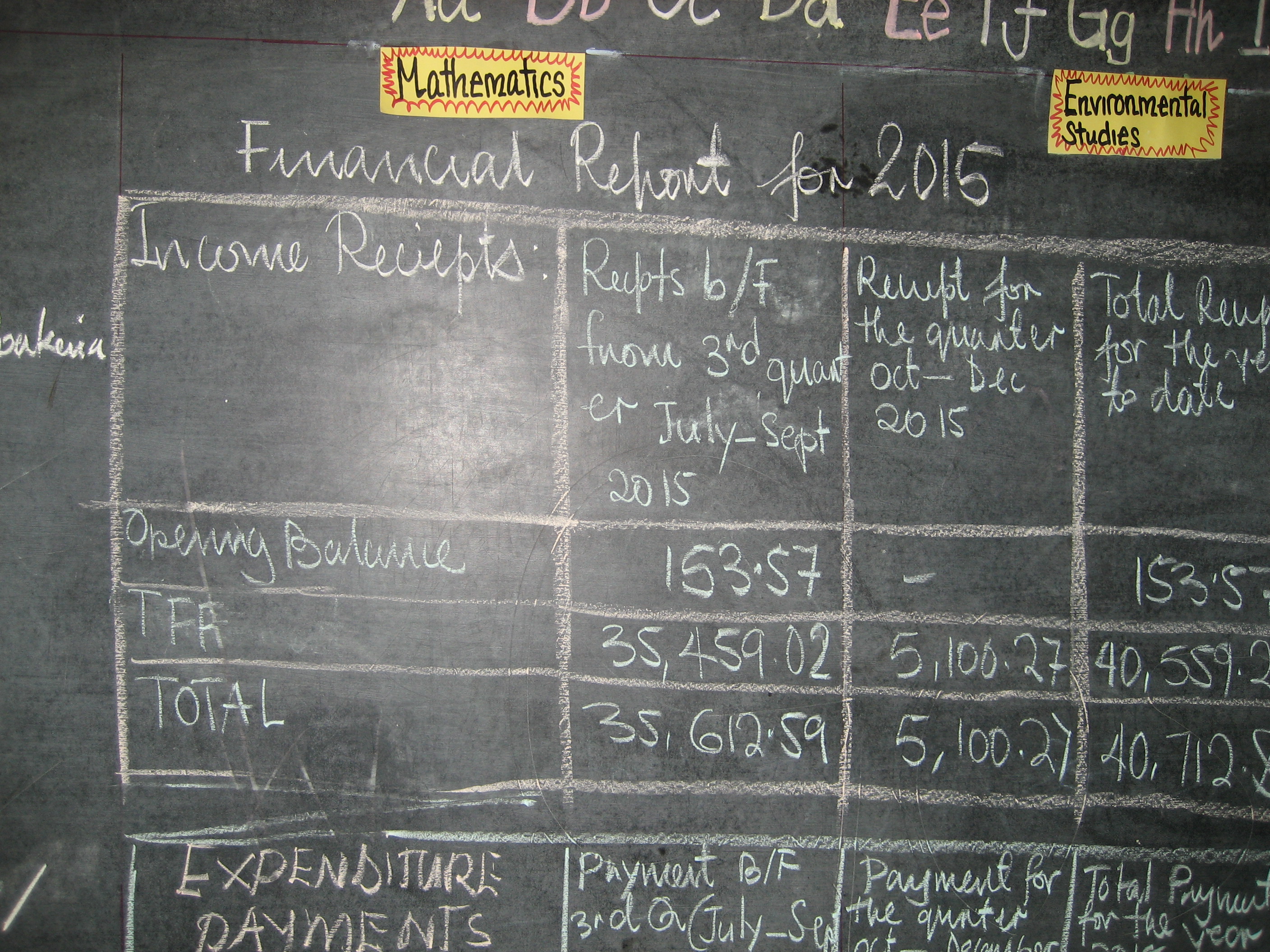

At the start of this year the PNG Government announced it would split the TFF payment into three components: a cash administration component of 40 per cent; a teaching and learning component (for school materials) of 30 per cent; and an infrastructure component of 30 per cent. According to the policy, schools will only be paid the cash administration component, leaving 60 per cent to be distributed by government officers. While the government has had a policy of retaining funds for teaching and learning materials for the past few years, this new policy means that funding for infrastructure will be held in a trust account in district treasuries. The distribution of these funds is to be decided on by district officers through newly established District Education Implementation Committees (DEICs).

During the recent pilot research in Central Province we were told that its DEIC had its first meeting a week before we arrived. According to one district officer, the committee included the District Development Authority (DDA) CEO (District Administrator as Chair), the District Education Superintendent, Education Standards Officers (inspectors), as well as community, women’s and church representatives. This is a good start – it suggests that, unlike the distribution of the MP-controlled District Services Improvement Program (DSIP), those engaged with managing the education sector have a formal seat at the table. In addition, more centrally controlled district management of these funds may have its advantages – funds can potentially be pooled and devoted to large-scale projects that, by themselves, schools wouldn’t be able to afford on their own.

However, our initial research suggests there is reason for concern.

For a start, in Central the DEIC was chaired by the DDA CEO, who is appointed by the MP for the electorate (normally made up of one or two administrative districts). In the words of another district officer, “The CEO will never say no to the MP. If he says no, he is at risk [of losing his job]”. It is very possible that, in some electorates, the MP could wield influence over spending decisions through the DDA’s CEO. There was also some suggestion that the new committee would have limited powers, with one member of DEIC suggesting that it would advise the DDA on how to spend funds. He said the DDA, which is heavily influenced by the MP and Local Level Government Presidents, would ultimately decide on funding. District officers said that DSIP funding was being directed to shore up support for the MP as well as LLG presidents at the 2017 elections.

In the two primary schools we visited, there was apprehension about what these new committees would mean for funding allocations. One teacher said that even though they thought the TFF was a good policy, the DEICs were “not a good initiative, as we may not get the money we are supposed to”. Given that three million kina of promised district funding for education infrastructure in 2015 reportedly never arrived in districts across the country (through the District Education Improvement Program), this fear is justified.

Putting decision making powers in the hands of district officers also increases risks of shonky contractors. At one school a contracting company employed by the district to build a classroom block in 2012 was allegedly connected to a member of the DDA. The contactor reportedly received 200,000 kina but failed to finish the job and vanished, forcing the school to use 15,000 kina of its own money. The building was completed but poorly built. In comparison, both schools had examples of the school managing, funding and building teachers’ houses and classrooms. They engaged community members in the builds – in one example, the president of the school’s Board of Management (BoM) was himself in charge of the construction. In both schools these buildings were in better condition than those built by outsiders.

As schools are no longer able to raise their own revenue – due to a ban on collecting project fees – they are now almost completely reliant on the government for funding. One school sought our advice on how they could get around this policy. One respondent asked if they could “fundraise” within the community without being accused of charging project fees. While this would be in breach of the government’s current education policy, the question suggests a sense of desperation about how funds might be sourced to provide schools with greater autonomy over their funds; particularly given the tendency for the government to pay subsidies late or less than budgeted.

Respondents were also concerned about how the ban on project fees might impact on community engagement. Members of the Parents and Citizens Committee and BoM still play an important role in supporting teachers, maintenance, infrastructure development and cleaning the schools. But, in the words of one teacher, when schools charged fees:

The community engaged with the school, helping out. But they are not doing [as much] now, even though we still need them to engage because the funding we get is not enough

A BoM women’s representative echoed these sentiments saying, “imposing project fees has made parents slack”. In the midst of great uncertainty about the timing and amount of funding available to schools, current government policy may be restraining local community engagement when it is needed more than ever.

We went to well-performing schools where most Grade 8 students go on to secondary school. Undoubtedly poorly performing and remote schools (and district administrations) will have different issues to contend with. Yet, the concerns that this initial research raises provide food for thought for policy makers and others seeking to understand the impacts of recent education policy reforms in PNG.

The government’s new TFF policy is clawing back decision-making over school resources, and recentralising decision making to the district level. This is a gamble given the initial success of school management over TFF funds on the one hand, and the mixed results of district funding and late TFF payments on the other. As DEICs roll out across the country, analysing and understanding their impact will be critical. That is something we will do – albeit on a modest scale – in the next phase of this research project, as we visit provincial and district administrations and schools in Gulf (a generally poorer performing province) and East New Britain (a province renowned for good service delivery outcomes).

Peter Kanaparo and Denise Lokinap are lecturers at the University of Papua New Guinea’s School of Business and Public Policy. Colin Wiltshire is a Research Fellow with the State, Society and Governance in Melanesia (SSGM) Program at ANU. Tara Davda is a Research Officer and Grant Walton is a Research Fellow with the Development Policy Centre.

This research is supported by the Australian Aid Program through the Pacific Governance and Leadership Precinct, as part of the ANU-UPNG Partnership.

Health and Education spending in PNG could be likened to a reverse feeding chain. Instead of the minnows and sardines first getting the plankton and then becoming food for the pelagic fish like tuna that are then eaten by sharks, the sharks are gobbling up all the food with any crumbs left for the larger fish with nothing for the sardines and minnows that actually support the food chain. In that scenario, clearly something will inevitable collapse.

People who live in a ‘western style country’ don’t seem to be able to comprehend that the same values and structures aren’t available or have been allowed to atrophy due to lack or attention or by design in a ‘developing country’.

A few years ago in Milne Bay, it was reported in the PNG media there was a large gathering of press, health care workers and people who witnessed a local member handing over a large cheque to assist the local Hospital. After the media had taken photos of the presentation and departed the member told the surprised hospital staff how they were now to re-credit the cheque to his personal bank account.

Anecdotes I receive indicate that all levels, corruption bleeds any available government funding to the point that very little reportedly reaches those who are actually in need of it. Apparently, the view of an increasing number of those in responsible positions is that if the opportunity exists, take it. If the PNG government sets the precedence, why resist some may say?

Update: The Minister for Education, Nick Kuman, has recently suggested that, while approved by Cabinet in late 2015, the DEICs have yet to be implemented throughout the country, with mechanisms still to be finalised.

Subsequent fieldwork in Gulf and East New Britain has confirmed that these institutions are not in operation in these provinces, although there is much concern about how they might work in practice once they are rolled out.

Hi Grant, I am very interested in getting more info on this newly created DEICs. I come from Gulf Province and has been at some point in my professional career being a teacher with 2 years in Kwikila, then 2 years in Passam, 1 year in Aiyura and a year at UPNG undertaking my PDGE. My spouse has been teaching for the last 28 years in secondary schools including 2 years in a primary school right across this beautiful country. Furthermore I have been a school board member at primary, secondary & international schools over the last 20 years across the country. At present I am a member of a BoM’s sub committee (Infrastructure) for the school my 5th born son attends year 11 in NCD. My work in the (O&G Industry) takes me back & forth between my home province (Gulf) and Port Moresby. Thus, I am very interested in your research report on the DEIC in Gulf (& East New Britain). The DEIC I presume is a new policy hence its objectives maybe very good, but the actual implementation may face some impediments along the way. Your report on the DEICs in the two Districts in Gulf Province would be very informative to me. Your feedback will be greatly appreciated. my contact details are stated below.