I was far enough into the mountains for the air to be fresh. The village was tidy, the paths between the houses carpeted with grass. Views spilled away in every direction: sea, islands, the spine of the land.

“Our MP has helped us,” the man, in his mid-forties, told me. “Small projects, roofing iron, help with houses. But we need something different. We need development. It’s not easy here.”

I’m paraphrasing, he didn’t actually use the word ‘development’, but that’s what he meant. And life wasn’t easy. Social capital was high, but the track in and out was long, steep and slippery. Everything, from produce, to housing material, to people in need of major medical help, had to go up, or down, the path. Stores, ports, hospitals and secondary schools were all a long way away. Worse still, logging and mining companies were circling, greedily eyeing the nearby forest and land.

A well-run government could change all this. It could regulate to prevent extractive industries from causing harm. It could bring roads, or at least improve the track, and help the villagers with access to the rest of their country. It could provide services. It could bring development.

And yet successive Solomon Islands governments have failed to do any of this. Their task wasn’t made easy by the country they inherited from the British, which was poor and lacking in infrastructure, but that’s not the whole story. There’s also been much political mismanagement since.

Some of the reasons for this mismanagement are easily understood: the corrupting power of logging money, for example. Others are less simple. Not all Solomon Islands politicians are corrupt – many care for their country. And Solomon Islands voters aren’t the problem either. They – very sensibly – vote for candidates who will help them, their families, or their communities directly. Their needs are immediate, and electing only one MP out of 50 can’t change the country. Real change requires 26 seats in parliament. Australians are spared such political collective action problems by cohesive political parties, which allow voters to vote for a national vision, confident that people around the country are doing the same. In Solomon Islands, where parties are fluid and fractious, voters can’t do this. So they do their best: they vote for candidates that will help them directly. It’s sensible, but it selects and incentivises candidates to concentrate on distributing material goods to their supporters rather than governing the country.

In the lead up to the 2014 general election, there was an effort to strengthen political parties through legislation. In the short term the 2014 legislation had the opposite effect from that intended. In 2014 most MPs stood as independents, seeking to maximise their ability to switch from side to side as the government was formed.

Other aspects of government performance didn’t improve either – politicians showed no more interest in national governance than before. Strong political parties are a missing ingredient from Solomon Islands politics, but they won’t be built by legislation.

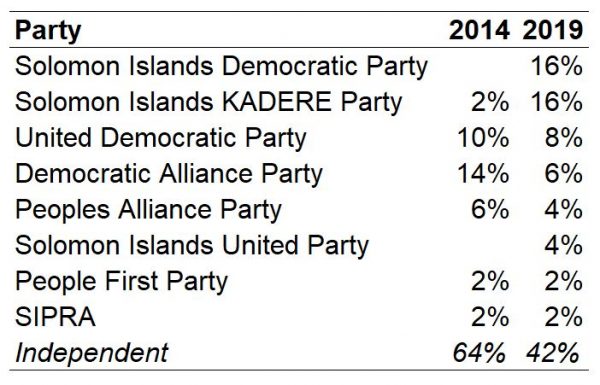

In 2019, parties staged a comeback of sorts. As the table below shows, thanks to the rise of the Solomon Islands Democratic Party and the Kadare Party, the number of winning candidates associated with parties rose. And yet the process of government formation has been as fluid as ever. Since the election, new parties have formed and MPs have switched allegiance back and forth between possible governing coalitions. In my time in Solomons for this election I didn’t meet a single person who voted along party lines.

At the same time as parties have failed to bring national political coherence, another response to the voter-politician relationship has come about in Solomon Islands: the constituency development fund (CDF) – government money topped up with Taiwanese aid that MPs are allowed to spend more or less as they will in their constituencies. CDFs have grown to a point where, alongside a terminal grant gifted to MPs just before the election, they confer a major incumbency advantage.

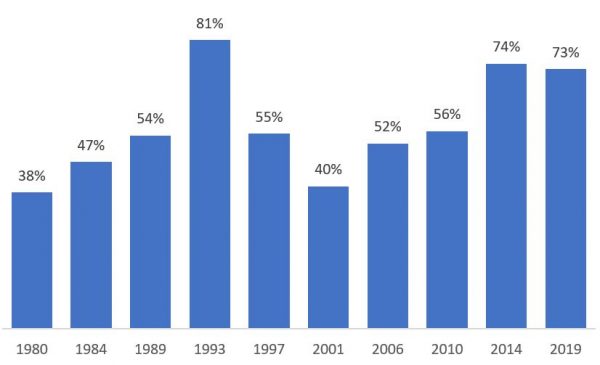

A few of the big names of Solomon Islands politics failed to be re-elected in 2019: former PM Derek Sikua; former militant Jimmy Lusibaea; Malaitan powerbroker Steve Abana; and Snyder Rini, whose election as Prime Minister in 2006 sparked riots. But, as in 2014, most sitting members were re-elected. As the chart below shows, this is a clear break from the long-run average. It’s hard to think of any explanation for this other than CDFs.

Incumbent re-election rate (share of contesting incumbents who win their seats back)

In a different type of democracy, we might celebrate having more experienced old hands back in power. But it’s hard to feel this way in Solomon Islands. There’s no evidence that long-term MPs perform any better in governing the country than newcomers do. And CDF funding brings a real political inequality with it. Today’s political elites are likely to be tomorrow’s political elites, and so on. Except in very particular circumstances, toppling a sitting MP now requires a lot of money, meaning the pool of people who might end up in parliament is much reduced.

And yet, it was CDF funding that had brought the small projects my interlocutor described to me as we sat in that small village in the mountains. His member had used his CDF well and villagers had benefitted from it, particularly those who had voted for the MP in 2014.

This is not nothing. By going with the grain of Solomon Islands politics, CDF funding provides some people with assistance in a country where the state so often fails to help. Roofing iron is a real improvement on a thatch roof.

The trouble is – as I was told as I sat there – small projects may help, but they’re no substitute for development.

Leave a Comment