In the wake of New Zealand’s recent election, and subsequent coalition negotiations, Winston Peters has emerged as New Zealand’s foreign minister again. I’ve never been able to adequately explain to Australian readers (or myself) why a populist politician leading a party called New Zealand First would have an interest in a post that takes him overseas so often. But there you go. Peters is foreign minister and, because New Zealand has no minister for development, he’s the politician in charge of New Zealand’s aid program.

Fortunately, for those who want to work out what Peters will mean for aid, he has a track record. He was first elected in 1978. Although he’s been voted out numerous times since then, at some point in his political wanderings he clearly stumbled upon a pile of political athanasia pills. He keeps coming back. As he’s done this, he’s managed to snaffle the role of foreign minister in coalition agreements with the centre-left Labour party twice, in 2005 and 2017.

In his first two stints as foreign minister he was responsible enough. He proved very capable at playing the role of statesman and diplomat overseas. He also did the dreary back-office work that ministers need to do efficiently. When it came to aid – although it’s almost impossible to know Peters’s real views on anything – he appeared to believe New Zealand had a genuine obligation to help the Pacific.

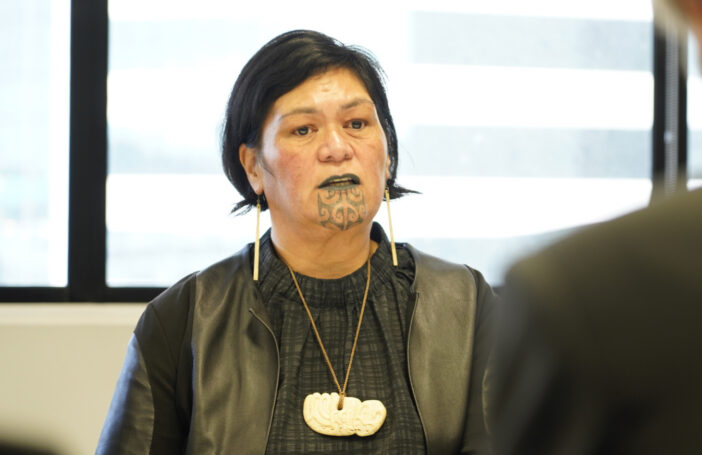

Beyond that, he was hands-off and happy to let the aid program be run by NZAID (in his first term) and MFAT (in his second term). By the time of his second term as foreign minister this was suboptimal – as I pointed out in my assessment of Nanaia Mahuta’s tenure as minister, the aid program has numerous problems and could do with a minister who pushed it to improve. On the other hand, as former foreign minister Murray McCully demonstrated with such vigour, aid programs can suffer worse fates than hands-off ministers. Much better a minister who doesn’t meddle than a hands-on minister who thinks they understand aid when they don’t.

Peters was also able to use his role as a lynchpin in coalition governments to get the New Zealand aid budget increased. I don’t know whether this reflected a sincere desire to do more good in the world or whether he simply wanted the prestige of being a minister presiding over a growing portfolio. Either way, it was a useful achievement.

This time round matters will likely be different though. Peters will probably continue to be a hands-off minister. But the government he is part of is conservative, comprising Peters’s New Zealand First, the centre-right National Party (the largest member of the coalition and currently Morrison-esque in ideology), and ACT, a libertarian party. New Zealand is currently running a deficit. And the government has promised tax cuts. It is unlikely there will be money for more aid.

Peters himself uses right-wing rhetoric to win votes and – to the extent his actual views can be divined – is conservative in many aspects of his politics. (He only ended up in coalition governments with Labour because of bad blood between him and earlier National politicians.) Peters, who is 78, doesn’t appear to care about climate change. He is also a strong supporter of New Zealand’s alliance with Australia and the United States. His views in both of these areas are shared with National and ACT, which could be bad news for New Zealand’s recently improved climate finance efforts. It may well mean a stronger stance on China’s presence in the Pacific too, with the result that geostrategy casts an even larger shadow over the quality of New Zealand aid.

On the other hand, it is possible that even the current government will start to feel embarrassed turning up to COP meetings and having to admit it’s doing less to mitigate its own emissions and less on climate finance too. Similarly, New Zealand’s politically conservative farmers need China as an export market. Perhaps a mix of political economy and international political economy will moderate the government’s approach to the new cold war in the Pacific.

Winston Peters has a track record. But he has never been predictable, and now he’s part of a very conservative government, in the midst of uncertain times.

“Predictions are difficult”, Yogi Berra is said to have quipped, “especially about the future”. It’s currently a very hard time to predict the future of New Zealand aid, even with a familiar face at the helm.