Another in our series on AusAID’s latest performance reports: for others, see here, here, here and here.

AusAID’s Office of Development Effectiveness (ODE), in its response to the Independent Review of Aid Effectiveness, no longer undertakes the often belated Annual Review of Development Effectiveness. This publication has now been replaced by two reports on the quality of Australian aid. But in the process, has ODE changed its approach from constructive critic to agency advocate?

The following is a review of one of these reports: ODE’s assessment of AusAID’s internal activity and program performance reports for 2009–10. Stephen Howes has provided a good critique of the other report [pdf] in its use of international indicators, sourced from the Brookings Institution.

An important conclusion of the former report, which is titled, ‘The quality of Australian aid: an internal perspective’ [pdf] is the following (p9):

The evidence presented in the 2010 Annual Program Performance Reports suggests that increasingly, aid is less about the transfer of resources and more about ideas, institutions and being a catalyst for change. It is about political as much as technical issues. AusAID’s main challenge is to ensure the agency has the capacity and systems to operate in this context.

How well are AusAID’s capacities and systems rising to this challenge? The best possible spin is placed on the results. The key finding highlighted is that ‘the integrity of the performance and reporting system is improving steadily’.

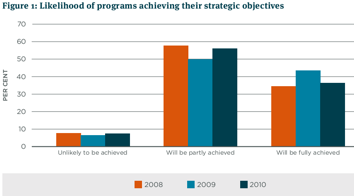

Of the 20 major programs which conducted an Annual Program Performance Report in 2009-2010, the report notes that 92.5 per cent of the program objectives are expected to be either fully or partly achieved. However, we have to guess from a graph (below) what proportion of programs are likely to achieve fully their objectives – it appears to be only about one in three. We are not told what the 20 country or regional programs are or where they can be found on AusAID’s website.

ODE explains away the decline in the proportion of major programs likely to achieve their objectives between 2009 and 2010 in the following terms: ‘rather than indicating a decrease in actual performance, this result may well reflect the fact that the performance reporting system itself is producing more sophisticated information’ (p2).

ODE explains away the decline in the proportion of major programs likely to achieve their objectives between 2009 and 2010 in the following terms: ‘rather than indicating a decrease in actual performance, this result may well reflect the fact that the performance reporting system itself is producing more sophisticated information’ (p2).

These Annual Program Performance reports have had major limitations as self-assessments. A footnote (p3) refers to an unpublished independent quality review of the 2009 reports which identified a range of major problems: inadequate information systems, a lack of clarity on what program performance means, weak or absent performance assessment frameworks, limited staff capacity in the area of program results, and insufficient incentives to change work practices.

ODE, however, claims that there have been marked improvements in the quality of the reports in 2010. These are said to include: a deeper understanding of the links between activities and strategic objectives; improved capacity to report on how Australian aid is aiming to ‘make a difference’; greater use of partner government results frameworks; increased reflection on aid effectiveness issues; identifying critical data gaps to inform sector programs; and offering more considered ratings of progress.

Unfortunately, no figures are presented from the content analysis on how well the problems identified in the 2009 review have been addressed or how widespread or deep these identified changes are across the 20 program performance reports.

ODE identifies seven challenges to Australia’s aid program but few are directed at AusAID. The first challenge is ‘weak or inconsistent partner ownership and low commitment to reform’ but the issue of how AusAID can improve its way of engaging in policy dialogue with partner governments is not addressed. The need for AusAID to concentrate more on particular sectors is highlighted but again no indicators are presented on the current state of play to provide a baseline benchmark for future assessments. The use of partner systems is identified as a challenge but no statistics are offered. The challenge of streamlining coordination and harmonisation processes is reported, based on the performance report feedback but no suggested ways of responding to these problems are offered. Engaging with emerging donors (eg China) is the final challenge listed but no suggested responses are proposed.

In summary, the main weakness of the ODE assessment of the quality of Australian aid delivery is ODE’s heavy reliance to identify key issues on the on-the-ground assessments of AusAID staff who wrote the individual country and regional Program Performance Reports. The absence of independent performance data on aid delivery gives this report a narrow and defensive tone which offers little guidance and incentive for AusAID to change.

The Government’s response to the Independent Review of Aid Effectiveness noted that ‘the Office of Development Effectiveness (ODE) produces an annual report that critically assesses what Australia has achieved and what we can do better’ (p12). The latest annual review reports from ODE have largely failed to show how aid can be delivered more effectively.

Richard Curtain is a Melbourne-based, public policy consultant, who has spent 18 months in Timor-Leste in 2008 and 2009, working on projects funded by USAID, UNICEF and AusAID. His current work for two major multilateral agencies in the region relates to Timor-Leste and to pacific island countries. For Richard’s review of the previous Annual Review of Development Effectiveness, written a year ago, click here.

I think the recent debate directed at the limitations of Australian Aid effectiveness data is helpful and important. However, I also think the heavy criticism hoisted upon ODE and AusAID misses the point a little on the development effectiveness agenda within the organsation. As one of the few professional evaluators to have worked in AusAID, I think it is important to acknowledge the limitations of what ODE has to work with. The reporting culture in AusAID is traditionally and continues to be weak. Datasets are poor, good baselines are rare and the political imperative of reporting in sound bites is common. This means strong, rigorous and thorough impact reporting is virtually impossible for most programs due to the poor systems and structures built into the aid delivery model. ODE and the Operations Division of AusAID has begun to tackle this by driving a cultural change built around the ‘self-reporting’ performance system of the agency. This system is based largely upon a World Bank model that looks to regular reflection on how programs are tracking against standard DAC measures (relevance, effectiveness, efficiency, M&E, sustainability and gender). While this reporting is completed by AusAID officers, there is a moderation process carried out by the Operations Division and then a realism review carried out by an independent consultant through ODE. The quality and robustness of these reports varies enormously and they range from the abysmal to the impressive. What is important when we critically dissect the process is to remember that it is still new, most officers are still lacking the skills to really make the assessment work, and we are going from virtually no discussion of accountability and performance to a dialogue now informed by a call for better skills and greater rigour. The system is riddled with faults and limitations, but there are a range of committed individuals working hard to make it work. To single out one good example, the Inodnesia program in AusAID has instilled an impressive M&E regime in the last three years. Working on many fronts, they have built in protocols for evaluation report release, they insist on management responses, they have a set of M&E standards, they have a professional development program supporting staff in the Jakarta office and they have a Minister Counsellor committed to cultural change. This is impressive for a program that was publishing less than 5% of its evaluations four years ago.

Having recently joined the World Bank, I continue to be stunned by the poor datasets that exist in the development aid world. I argue that part of this is driven by an obsession with data, indicators and information that does not mean anything, does not help anyone and is not utilised in interesting ways. We should remember that part of the performance mandate is about what we learn and how this is used. Yes, ODE have missed some opportunities to more strongly impose themselves on the effectiveness agenda, but I believe the analysis they conduct on the APPRs and on the annual quality at implementation (QAI) reports is actually very good. The sampling is sensible, the consultant has worked on the review for each of the four years the system has been in place, and there have been identified changes in the quality of the regular reports. Yes, the process is qualitative and yes the tracking data is still limited, but the report is a review of the existing system and at this stage I don’t think it warrants constructing an in-depth range of tracking information. To do this would mean further challenges to an already stretched and inexperienced staff and the danger that they freeze like deer in headlights. I believe there are enormous opportunities for stretching the work ODE does and inviting them to be involved in an informed discussion on approaches and methodologies would be a good place to start. Believing that people, organisations and stakeholders will always make good use of data and the transparency charter is naive as the regular press articles by Steve Lewis will attest. Having a robust discussion of the best ways to make aid programs more ‘effective’ is a much bigger challenge than simply hoping that ODE can lift its game in its very limited mandate. Now that I am outside the public service I look forward to being more involved in this discussion.

Christopher Nelson is a M&E Specialist with the World Bank based in Sydney. He previously worked in the Performance Effectiveness and Policy Division at AusAID.

Christopher, thanks for your insider’s assessment of the state of the ‘reporting culture’ within AusAID. You note that the Office of Development Effectiveness (ODE) has poor quality data and systems to work with.

An important issue is the timing of the release of the country annual program performance reports (APPR). I have recently travelled to a number of countries in the Pacific to present a workshop. I sought information from the AusAID website for each country, only to find APP reports were up to three years out-of-date. Tonga’s report for the financial year 2007-2008, was released in November 2008, but the reports for Samoa and Nauru was for 2008-09, released in June & July 2009 respectively. For Kiribati, the APPR is for the year 2008, released in November 2009. For Solomon Islands, no APPR was on the website, only an undated document on the two countries Partnership for Development. No report was available for Fiji although reports on three specific program dated 2011 were available.

Information has to be timely to be effective. It may be partly to do with the uneven capacity of its staff in its country posts, as you highlight (‘most officers are still lacking the skills to really make the assessment work’). It may be to do with the extended internal processes AusAID has vetting these reports before handing them to an external consultant to validate.

You also note that AusAID’s self-assessment system is ‘riddled with faults and limitations’. ODE needs to provide this feedback, and report publicly on the extent of improvements in staff capacity and system performance. AusAID and ODE need to appreciate that there is an audience out there who want more than superficial assessments of aid activities. We want up-to-date information on results achieved. We also are looking for a good situation analysis of each country, based on honest assessments of limitations of program design and delivery, host government shortcomings and the lessons learned.

Richard Curtain

Richard, thanks for your comments. As far as publication is concerned, I have just been to the website and in the section on publications under Annual Performance Reports you will see almost the entire selection of reports for 2010. Any reports not there were unavailable for publication when the final vetting process was done, but the publication numbers have improved each year and the Operations section should be commended for lifting the number of reports published. I am not sure if you were looking at the country sites and this is probably a limitation of the website that cross posting is inadequate. There has also been labelling issues in the past regarding dates as the data differs from one country to the next based on when country reporting is done. Where reports are missing, I would suggest highlighting this as an inadeqaute response from the given program as external pressure will ensure country programs take reporting seriously. This has been a major problem with certain sections in the agency and thus external pressure such as this blog is very helpful.

I also agree that ODE needs to be more explicit in its criticisms of the system. This is provided in feedback provided to the operations group, but more hands on analysis by ODE would make constructive improvement more immediate and realistic. In essence, I think your points are well made and helpful. Where I would like the debate to go is to the crux of how best to report on ‘results’. There is a real danger that simplistic external pressure will drive programs to look for easy things to measure, rather than adequately dealing with the efficacy of our aid program. Encouraging programs to simply focus on outputs and numbers because they are easy to track will not lead to lasting impact which is a much more nuanced challange. Having a realistic debate on emergent issues in tracking development aid would be a good place to start.