Australian aid

The 2024-25 federal budget update, released in December, contained additional funding to support the provision of $100 million over five years in budget support to Nauru as part of a new bilateral treaty. Much of this funding will not be able to be counted as Official Development Assistance (ODA) as Nauru is scheduled to be removed from the list of ODA eligible countries from January 2026. This is largely a result of the increased income per capita effects of Australia’s ongoing funding for the country’s regional refugee processing centre and growth in Nauru’s revenue from the sale of fishing licenses.

The Albanese government has proposed to Timor-Leste that a new infrastructure fund, capitalised from part of Australia’s share of future revenue from the stalled Greater Sunrise gas project in the Timor Sea, be established “to support any commercially viable solution proposed by the commercial parties” that is agreed to by the two countries.

Australia has allocated $17 million in assistance to date to meet relief and reconstruction needs in Vanuatu following the country’s 17 December earthquake. In December, the government allocated $76 million to help meet ongoing recovery, reconstruction and energy needs in Ukraine.

Australian NGOs have called on the Albanese government to provide a further $50 million to help address the humanitarian crisis in Gaza in the wake of the announcement of a six-week ceasefire deal between Israel and Hamas. They have also urged the government to continue to lead global advocacy efforts to improve protection of aid workers. The UN estimates that more than 330 humanitarian personnel have been killed in Gaza since 7 October 2023. Israel’s unilateral ban on the largest aid organisation operating in Gaza, the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), came into effect on 30 January.

Late 2024 saw the announcement of new donor commitments to the latest funding calls from several key multilateral development and global health bodies. Australia’s new multi-year commitments to the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Pandemic Fund have been published by these bodies. Australia’s contributions to the World Bank’s International Development Association and to Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, are yet to be announced (see Table 1). As expected, in one of his first official acts, President Donald Trump signed an Executive Order to begin the process of withdrawing the US from the WHO, a decision described by one set of experts as “a global public health crisis in the making”.

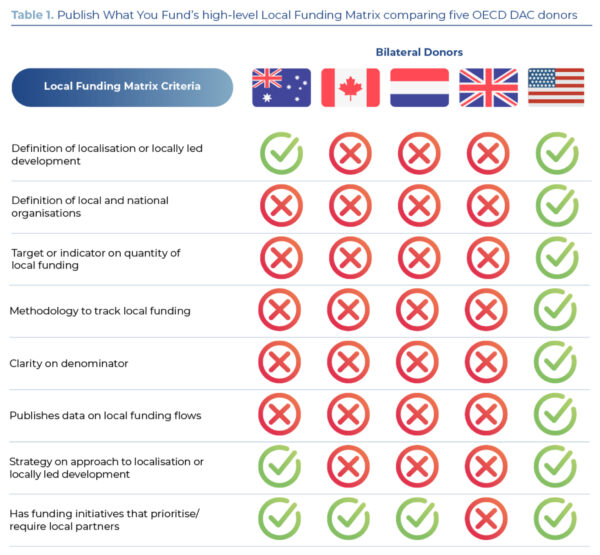

Publish What You Fund has compiled an assessment of five donors’ implementation of commitments relating to locally-led development. Australia fares comparatively well (it ranks second overall after the US), but it is found wanting when it comes to five of the eight implementation and accountability indicators (see Table 2).

Table 2: Publish What You Fund’s high-level local funding matrix

Source: Publish What You Fund, Commitments without accountability: the challenge of tracking donor funding to local organisations, December 2024.

Australia is scheduled to be the subject of an OECD Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC) peer review of its international development policies and programs in 2025.

Regional/global aid

New Zealand has said it is reviewing its aid to Kiribati after the country’s president and foreign minister, Taneti Maamau, cancelled a scheduled meeting with New Zealand’s deputy prime minister and foreign minister, Winston Peters.

Indonesia and Germany have signed a new debt-for-health swap agreement which will convert €75 million (A$125 million) of Indonesia’s debt into investments to support malaria control, enhance health systems, promote local production of medicines, and assist Indonesia’s fight against tuberculosis.

Devex reports on what February’s snap elections in Germany might mean for aid from Europe’s largest donor country and on the OECD-DAC chair’s rare public call upon the European Union (EU) to uphold its commitments to prioritise aid to poorer countries in response to ongoing changes to the EU’s aid policy, budget and management structures.

In the final weeks of its term, the Biden administration bolstered US humanitarian aid to Sudan, allocating an additional US$200 million (A$320 million). This brings its total assistance to help combat the country’s conflict, hunger and displacement crisis to US$2.3 billion (A$3.7 billion) since 2023.

Citing war crimes such as using food deprivation as a tactic of war, the outgoing Biden administration sanctioned Sudan’s de facto president, General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan. It also sanctioned al-Burhan’s rival, head of the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) Mohamed Hamdan Dagal and several RSF-owned companies based in the United Arab Emirates on the grounds of genocide.

In the wake of the toppling of the Syrian government led by President Bashar Al-Assad in December, the Biden administration moved to ease some of its financial sanctions on Syria to help facilitate increased humanitarian aid flows.

And outgoing US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen approved the disbursement of US$3.4 billion (A$5.6 billion) in direct budget support to Ukraine, the final tranche in a larger support package passed by the previous Congress in early 2024.

As well as moving to withdraw the US from the WHO and reinstating the “Mexico City policy”, which bans US funding to overseas organisations that perform or promote abortions, newly inaugurated US President Donald Trump has also signed an executive order announcing a ninety day pause on all foreign aid to allow for an “assessment of programmatic efficiencies and consistency with United States foreign policy.” A subsequent “stop work” directive suspends all US foreign aid disbursements and new obligations during this period. A temporary waiver exempting emergency food aid from the freeze has been expanded to encompass “life-saving humanitarian assistance”, which is defined as “core life-saving medicine, medical services, food, shelter, and subsistence assistance”.

Books, articles, reports, blogs, podcasts etc.

Ben Day and Tamas Wells have published the results of their latest survey of parliamentarians’ views of the Australian aid program in the latest edition of Asia and the Pacific Policy Studies journal.

Devpol’s Terence Wood and Stephen Howes publish the findings of a study using data drawn from Australia’s aid performance ratings to show that external reviews of these ratings can lead to significant falls in how successful projects are deemed to be.

The World Bank’s January 2025 Global Economic Prospects report highlights concerning trends for developing economies, which account for 60% of global growth. Growth in these nations is projected to hold steady at about 4% over the next two years, marking the weakest long-term growth outlook since 2000.

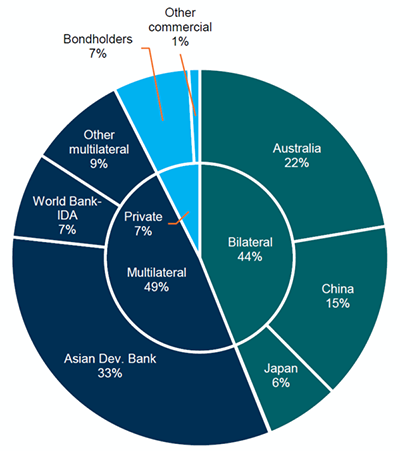

In its 2024 International Debt Report, the Bank estimates that developing countries spent a record US$1.3 trillion (A$2.07 trillion) servicing their foreign debt in 2023 with interest payments surging by almost a third. Australia is PNG’s biggest bilateral creditor (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Papua New Guinea — public and publicly guaranteed debt, by creditor and creditor type in 2023, including IMF credit

Source: World Bank, International Debt Report 2024, December 2024.

In an interview with Devex’s podcast, departing USAID head Samantha Power has warned against viewing aid purely as a tool of foreign policy: “Development and humanitarian work that gets entirely instrumentalised really does risk becoming so transactional and just bounded, in a way, by shorter-term considerations… And if you think about the kind of lasting impacts that USAID and development generally have achieved, it’s always a long game.”