If your clients are wealthy and deposit large sums in their accounts, banking can be a lucrative business. But if they are poor, sparsely grouped and make infrequent contributions to their account, economies of density, scale and scope are absent.

However, since 2005, recognising that this lack of pricing power has led to the exclusion of large sections of India’s population from traditional financial markets, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has introduced a series of policy initiatives to rectify this. Measures such as ensuring communities with a population of 2000 or more have access to a kiosk or financial outlet, enabling lines of credit through microloans, developing educational literature and creating reduced service banking models, are examples.

So it was a surprise to learn of the recent decision to cull frequently used rupee notes.

Before I explain why this is significant, here are a few numbers for your consideration. In 2010, more than 50% of Indians reported paying a bribe to facilitate a transaction, in 2008 the size of the shadow economy was estimated at around 50% of GDP, and between 2013 and 2015, the percentage of counterfeit notes detected in circulation had risen by almost one-fifth, with ₹500 and ₹1000 notes comprising the largest share of those detected.

Yet, despite this apparent financial fluency, approximately 40% of the population lack access to formal financial services. Prior to demonetisation, 86% of all circulated notes were ₹500 and ₹1000, and in 2015, cash transactions comprised more than 75%[1] of financial transactions (compared with less than one quarter in the US). Taken together, these figures suggest that most of the population are likely to have been affected by the decision, and at least half adversely so.

But which half? Although the currency cull was intended to catch counterfeiters unawares, there have been widespread reports that the move may have had unintended consequences for another group of high frequency cash users: the unbanked and underbanked.

In 2014, only 53% of Indians[2] held an account with a formal banking institution, while just 14% had savings. Of the poorest four deciles, only 44% owned an account. In rural areas, the problem is especially acute, where the share of individuals without a bank account is much higher [3]. With estimates that just 6% of corrupt profits are laundered through cash channels, it is not unreasonable to surmise that these are the cash users most likely to have been caught out by the policy.

Microfinance, an all-encompassing term for delivery of a set of financial products and services to low income businesses and individuals, has grown rapidly in India, providing poor households with a financial safety net and enabling them to smooth their consumption patterns, build assets and reduce vulnerability to economic stress. India has one of the largest microfinance industries in the world, and as word of the currency restrictions spread, the shortage of larger notes began to have a ripple effect. Demand for other denominations rose and subsequently reduced the supply of currency in circulation. Customers were unable to make microloan repayments, and the incomes of the daily waged (typically paid in cash), tumbled. Small businesses, reliant on smaller denominations for payment for goods and services, were unable to return change, and in some parts of India, particularly rural areas where access to banking outlets is sparse, trading activity fell by up to 90%.

As liquidation dried up, microfinance customers struggled to make payments, and in return, Microfinance Institutions (MFIs) grew increasingly leveraged, unable to finance their debt and lacking sufficient liquidity to extend lines of credit. Reports of a credit crisis among MFIs began to circulate, and in a move that signalled the extent to which lenders were in arrears, some institutions were forced to temporarily suspend disbursements.

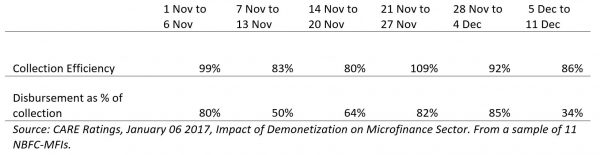

As the table above shows, in the weeks following the cull, the collection efficiency rate on microfinance loan recovery fell to around 80%. In the two weeks following the policy, collections fell by almost one fifth, and although the rate recovered briefly in the week beginning 14th November (likely a result of a cash injection by the RBI), the improvement reversed in subsequent weeks. By December 5, disbursements as a share of collection had fallen sharply, a decline attributed to a shift in MFI focus from loans to recovery.

The broader risk is that an industry contraction, caused by a sharp fall in collection rates, may result in a reduction in competition, driving up loan rates, and resulting in a net loss of welfare across the industry. Poor consumers will suffer because credit will cost more, financial sufficiency and stability will take longer and ultimately, economic development in rural areas will slow.

Although some of the impacts associated with demonetisation are likely to dissipate over time, others, such as the worsening of credit of both consumers who default and MFIs who are overleveraged, are likely to have more longevity. An industry contraction is also likely to have longer lasting effects on the sector.

Critics are divided on the success of the policy (here and here). Most agree, however, that if only holders of black currency had been affected, it might have been effective. Unfortunately, for all India’s good work on the use of financial tools for poverty reduction (here and here), demonetisation does not appear to have considered the impact on the unbanked, and through the broader unravelling of liquidity, on MFIs.

Tara K Davda is a Research Officer at the Development Policy Centre.

Notes:

[1] Source: IMAP, Industry Report, Payments Industry in India Q4 2016

[2] Aged 15 years and over

[3] 60% cf. a national average of 40%