Informal urban settlements are rapidly growing in the greater Honiara region, including peri-urban areas in Guadalcanal Province, with some areas growing at rates as high as 12 per cent per annum (SINSO 2012:21). Most informal settlements’ residents do not have legal land tenure and usually lack services, adding to urban inequalities. Government-led responses have been limited; the main initiative to date has been to offer informal settlers 75-year leases on state land (that is, ‘fixed term estates’), but the process has many bureaucratic steps and often ends with an insurmountable hurdle when most cannot afford the lease price, which can be over five times median incomes. Adding to frustrations, the process has also suffered from a lack of transparency.

Responding to growing pressures, the Solomon Islands Government is expanding its urban agenda to address deepseated urban management challenges. For example, the Commissioner of Lands who had sole responsibility (but little accountability) for allocating urban land has been replaced by a Land Board of 12 voting members in an effort to depoliticise land allocations. An informal settlement upgrading strategy, supported by UN-Habitat, is also taking first steps to address the nexus between land, services and governance issues, although progress has been mired by unclear roles and responsibilities from the local level up and concerns about how interventions may affect (informal) land access and power relations. National framing documents, including a national urban policy and a national housing policy, are also being developed, adding to the paper commitments. Getting traction will depend heavily on community engagement, political will and resourcing — all currently patchy.

This post reports on recent work, supported by UN-Habitat and donors, aimed at creating a profile of Honiara’s informal settlement situation and the challenges ahead. We then focus on one key missing element: the critical need to improve housing affordability.

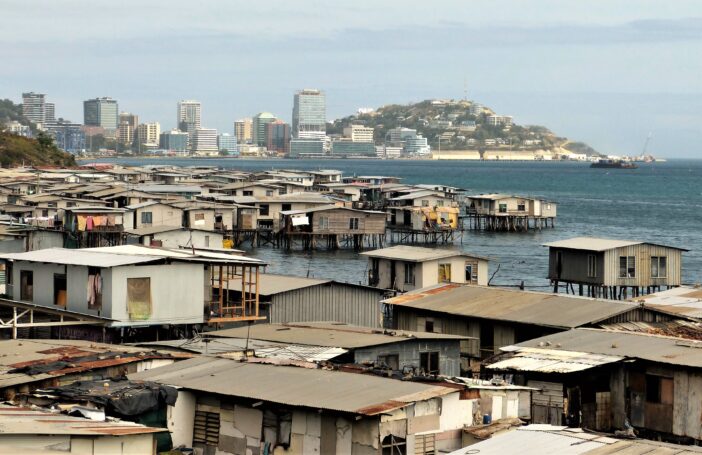

Mushrooming informal settlement

Best available information emerging from UN-Habitat’s profiling suggests there are close to 4000 informal settlement households within Honiara’s municipal area; that’s about 28,000 people or around 40 per cent of Honiara City’s population (UN-Habitat 2016). Many of these informal settlers live in 36 ‘informal settlement zones’ mainly on state land, a delineation created by the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Survey (MLHS) for administrative reasons. For most residents the boundaries between formal and informal parts of the city are irrelevant. A recent survey of residents from seven of these zones found only 5 per cent had a temporary occupation licence; all the other respondents either didn’t know what tenure they had (44 per cent), forgot (9 per cent) or claimed the information wasn’t available (42 per cent) (Pauku 2015:7).

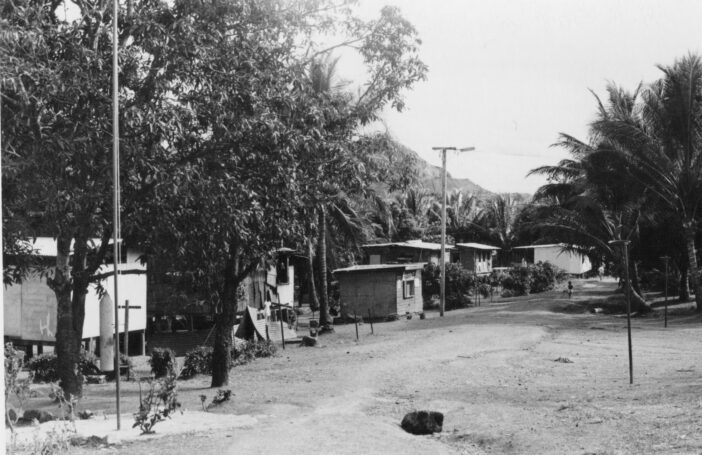

The most rapidly growing informal settlements outside municipal Honiara are on peri-urban customary and registered land in Guadalcanal Province. Numbers are unclear but likely in the hundreds, if not thousands, of households. There is little support for customary landowners wanting to develop their land, and there are few legal protections for those with informal agreements. Melanesian studies have found that adaptation, not replacement, of customary tenure is the preferable approach because it builds on existing arrangements (Fingleton 2005 [pdf]). Social acceptance of customary tenure is evident from Honiara’s housing investment patterns. Investment is correlated most strongly with time in place rather than legal tenure — particularly in informal settlements — which suggests de facto or perceived security of tenure is a key (but neglected) driver of investment; as in Fiji (Kiddle 2010 [pdf]).

Informal settlements are here to stay

The MLHS is now committed to upgrading informal settlements through subdivision planning and converting state tenure to leased land. There are plans for most informal settlements within the Honiara town boundary. The government has accepted the permanence of many informal settlements on state land. Evictions are extremely rare; actions reminiscent of the recent tensions related to ethnicity, land and economic benefits disputes, most intense between Guale and Malaitan ethnic groups on Guadalcanal, especially in Honiara, are avoided. The majority of informal settlers in greater Honiara are Malaitan.

Infrastructure and services — particularly better sanitation, solid waste collection, and access paths and roads — are rarely available in informal settlements. Refreshingly, both the major utilities are taking a more pro-poor, progressive attitude to informal settlements. The utilities have, for example, been piloting and planning ways to reduce costs of connections (Solomon Power) and introduce prepay mechanisms (Solomon Power and soon Solomon Water) to boost services to informal settlements. Even so, one utility executive noted they would be ‘chasing the people’ for a long time yet.

Other opportunities for better urban management exist. Coordination between key agencies — including national government, Honiara City Council, the utilities and nongovernment organisations — could be greatly strengthened. Financial shortfalls mean that development partners, both private and donors, will be needed for a timely and comprehensive settlement upgrade program, although cultural fit and sensitivity will be key. Importantly, Guadalcanal Province must be engaged much more. Concerned about the lack of inclusion in urban planning, one senior Guale politician made clear that process mattered for constructive relationships: ‘It’s not about opposing development, it’s about how government recognises [our] customary land … about getting revenue resources’.

One missing element: improving housing affordability

Tellingly, at the inaugural Solomon Islands National Urban Conference in June 2016 local delegates referred to informal settlements as ‘affordable housing areas’. This is no surprise. Honiara housing is expensive; a situation worsened during the RAMSI period and its large influx of staff. Solomon Islands Home Finance Limited (SIHFL) — charged with developing affordable homes — has been selling dwellings at SB$495,000 (AU$82,500) to SB$735,000 (AU$122,500) (SIHFL 28/6/2016) — that’s about 50 to 70 times the median wage. These costs are far, far beyond the reach of even the most senior civil servants. The result is that 97 per cent of SIHFL homes built in the past six years have been sold to the government to house public servants. Opening up more land for development, although difficult, is part of the answer, and that will mean working with Guadalcanal and customary landowners for sustainable solutions. Housing costs could be cut by requiring more modest, but safe, standards and creating higher density housing — all steps taken in Suva (Phillips and Keen 2016 [pdf]). New options are also needed: the MLHS is preparing legislation to allow strata titles, hoping to increase accommodation supply and reduce costs. There is also a push for cheap modular and prefabricated housing to cut expenses. Low-income public housing is needed, too, as provided elsewhere in Melanesia, but this is likely to need donor and/or non-government organisation partnerships to meet costs.

For most residents in greater Honiara, there currently remains no option but informal settlement because of high land and housing costs. Perhaps the forthcoming informal settlement upgrading strategy and national housing policy will generate new options. But progress will depend on addressing hard issues about locally appropriate ways to address the rapidly rising urban demands on customary land for which there are next to no formal supports, and on expanding affordable housing options. Without targeted and sustained action many more citizens will be ‘priced out of the market’.

Meg Keen is a senior policy fellow in the State, Society and Governance in Melanesia (SSGM) program at ANU. Luke Kiddle is an independent urban consultant who has worked for UN-Habitat on urban issues in Honiara. This post was originally published as SSGM In Brief 2016/28.

Meg Keen is a senior policy fellow in the State, Society and Governance in Melanesia (SSGM) program at ANU. Luke Kiddle is an independent urban consultant who has worked for UN-Habitat on urban issues in Honiara. This post was originally published as SSGM In Brief 2016/28.

References

Fingleton, J. 2005. Conclusion. In J. Fingleton (ed.) Privatising Land in the Pacific: A Defence of Customary Tenures. Discussion Paper 80. Canberra: Australia Institute, 34–7.

Kiddle, G.L. 2010. Perceived Security of Tenure and Housing Consolidation in Informal Settlements: Case Studies from Urban Fiji. Pacific Economic Bulletin 25(3):193–214.

Pauku, R. 2015. Slum Situational Analysis. Honiara: Ministry of Lands, Housing and Survey/UN-Habitat.

Phillips, T. and M. Keen 2016. Sharing the City: Urban Growth and Governance in Suva, Fiji. SSGM Discussion Paper 2016/6. Canberra: ANU.

SIHFL (Solomon Islands Home Finance Limited) 28/6/2016. Presentation at Solomon Islands National Urban Conference.

SINSO (Solomon Islands National Statistical Office) 2012. 2009 Population and Housing Census: Report on Migration and Urbanisation. Honiara: National Statistical Office.

UN-Habitat 2016. DRAFT Honiara City-Wide Informal Settlements Analysis.

In Solomon islands people live on the land in their respective locality, therefore, to use informal urban low cost housing as a prognosis to solve informal settlements is like asking the river to flow from the sea to the mountains or creating a wave of urban drift to our urban areas. The only solution is to pass a national rural growth development equitable distribution to our provinces in partnership with our rural dwellers who hold the wealth of our country. Having this mindset the national government should give their expertise to our Rural Dwellers front doors and give confidence to our people to give their all to our nation building.

Thanks Martin for the comment. I agree rural development is important. But globally urbanisation has been one of the defining trends of modern times. More movement to towns and cities is likely inevitable, including in Solomon Islands. Solomon Islands may need to accept – and adequately prepare for – this ongoing tide.

Thanks for the interesting article. It is hard though to see the use of cheaper formal-sector housing as a tool for slowing the spread of informal settlements. As you say, informal settlements are the solution to housing affordability. The focus, it seems to me, should be much more on the other things you suggest – the provision of services, and providing security of tenure.

Thanks Stephen. Fair point; it will be hard to enable cheaper formal sector housing, particularly at levels affordable for the majority of the urban (or soon to be urban) population without major government focus, and support from partners. It will be interesting to see what the ongoing housing work (housing profile, followed by the preparation of a national housing policy) focuses on.