On 27 May, a group of young leaders from Kiribati, Tuvalu and Papua New Guinea met in Canberra to lobby the Australian government to rethink their climate change policies. The effects of climate change are reported to have significant implications for communities across the Pacific Islands, with key effects including temperature increases, changing rainfall patterns, sea-level rise, floods and more intense tropical cyclones. Kiribati, the Republic of the Marshall Islands and Tuvalu consist of low-lying atolls, making them particularly at risk [pdf] to sea-level rise. Papua New Guinea, the region’s largest country, is expected [pdf] to experience greater risk from flash flooding and landslides across the highlands and coastal flooding along the south coast.

There are different possible responses to Pacific climate change, of which migration is one. Migration is a way for communities in the Pacific to cope with environmental change, alleviate pressure on existing resources, and given an appropriate policy context, to enhance development, thus allowing those who remain to better adapt to the effects of climate change. As such, migration can be seen as a constructive and positive adaptive response and can enhance the capacities of Pacific Island countries to adapt to climate change.

While New Zealand and the United States have been reasonably generous in facilitating migration from Polynesia and Micronesia respectively, Australia stands out with the greatest capacity to open up new migration pathways for Pacific Islanders due to being the closest ‘developed’ neighbour and having influential and continuing trade and aid relationships with many of the Pacific Island countries. Furthermore, limited opportunity for Pacific Islanders to migrate out of their home countries in response to the effects of climate change may increase resource scarcity, contribute to state fragility and exacerbate conflict, which can in turn have a greater impact on Australia.

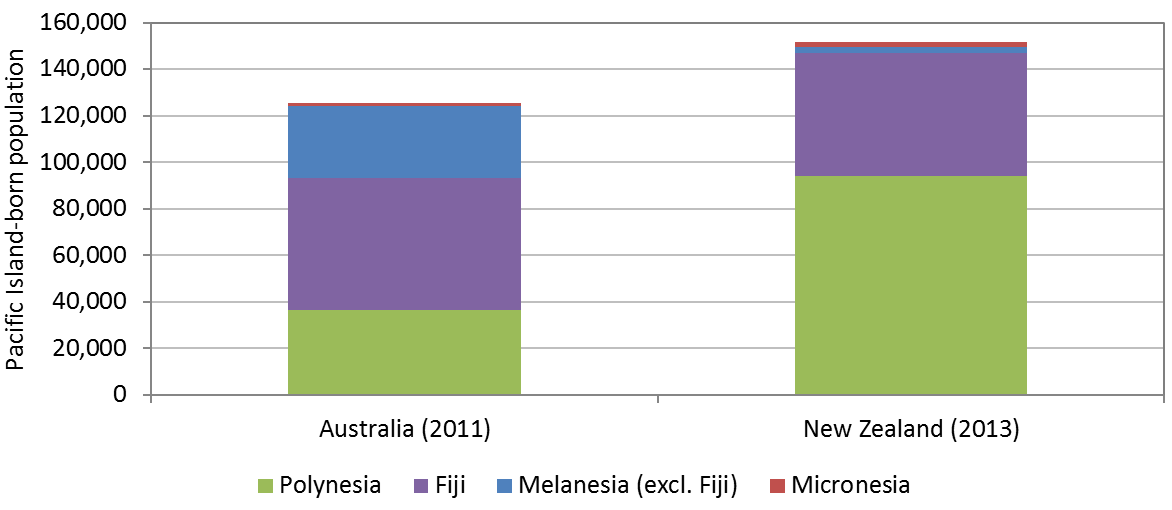

Currently, Australia has a small population of Pacific Island-born people relative to Australia’s overall population size. According to the 2011 Census in Australia, Pacific Island-born people only comprised 1.9% (125,506 people) of the total foreign born population (6,489,874 people), which is about 0.6% of Australia’s total population (21,507,717 people). The proportion of Pacific Island-born people in Australia is significantly less when compared to New Zealand (151,530 people), of which about 3.6% of New Zealand’s total population (4,242,051 people) is comprised of Pacific Island-born people as recorded in their 2013 Census.

As demonstrated in the figure below, those born in Fiji and Polynesia forms the majority of the Pacific Island-born populations in both Australia and New Zealand. As such, a number of countries in Melanesia and Micronesia, particularly those vulnerable to the effects of climate change, are identified as being disadvantaged by the lack of permanent migration options.

Population of Pacific Island-born people in Australia and New Zealand by sub-region

Sources: Australian Census of Population and Housing 2011 and New Zealand Census of Population and Dwellings 2013

Sources: Australian Census of Population and Housing 2011 and New Zealand Census of Population and Dwellings 2013

Despite this, the Australian government has not given any indication on making specific plans for opening up permanent migration pathways for people from Pacific Island countries. Rather, there is a preference for maintaining the current migration program, the Skilled Migration Program, which is not applicable for many Pacific Islanders due to the region’s population being generally comprised of low-skilled workers. In addition to the Skilled Migration Program, Australia offers temporary labour and training initiatives, such as the Seasonal Workers Program and the Kiribati Australia Nursing Initiative, for selected Pacific Island countries.

A potential barrier to Australia’s reluctance to facilitate migration from the Pacific Islands is the public discourse that tends to focus disproportionately on the negative impacts of immigration and in-migrants. Public and policymakers at the receiving country, such as Australia, may believe that migration can become an economic burden, as immigration is feared to lead to a loss of jobs, heavy burden on public services and welfare systems, social tension and increased criminality.

On 3 June, the Lowy Institute for International Policy, an independent, nonpartisan think tank based in Sydney, released the results of their 2014 poll on Australian attitudes to Australian foreign policy. Regarding immigration, the poll identified that:

- 37% of Australians noted that the total number of migrants coming to Australia each year is too high, compared with only 14% saying it is too low. About 47% said the current migrant intake is about right.

- To those who said the number of migrants each year is too high, concern about immigration is predominately concentrated on jobs. The two top reasons were ‘we should train our own skilled people, not take them from other countries’ (88% saying this was a major reason) and ‘having more people could make unemployment worse’ (87% saying major reason).

- Cultural diversity does not appear to be a primary driver of anti-immigration sentiment.

But do Pacific migrants take jobs away from the existing population and generate costs for Australia? Recent research and data suggests that many of the perceived costs of migration are unfounded and are in fact a negligible or positive impact on Australian society.

The 2011 Australian Census demonstrated that the unemployment levels of Pacific Island-born people were lower (5.0%) than that recorded for Australia as a whole (5.6%). In addition, Pacific Island-born people recorded higher levels of labour force participation in Australia (77.7%, compared to 65.0% for Australia as a whole), which can be attributed to the fact that Pacific migrants tend to be of a working age, while Australia’s population is rapidly ageing. In addition, Pacific migrants tend to take up the menial, low-skilled jobs that the general population may not want to engage in, such as manufacturing. As such, Pacific migrants can play a critical role in filling gaps in the Australian labour market.

In terms of fiscal and welfare impact, research published by the Department of Immigration and Citizenship strongly suggest that in-migration is beneficial to Australia’s economy overall, as with time, migrants contribute to fiscal surpluses. In addition, data recently released by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development indicate that migrants in Australia use less or the same amount of welfare services than the Australian-born population, suggesting that migrants do not burden welfare systems. Migrants can also substantially contribute to productivity and innovation, bringing to Australia new ideas and entrepreneurship.

There is also a widely held perception that increased migration results in increased crime. However, studies of crime and ethnicity tend to contradict this perception. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics and research conducted by the Centre for Applied Research in Social Science [pdf], migrants are less likely to commit crimes and be imprisoned than the Australian-born population, and the proportion of Pacific Islanders in Australian prisons has declined over the last decade.

Furthermore, the presence of Pacific migrants greatly enriches the cultural landscape of Australia. Most notably, they introduce new recreational and cultural activities that the wider population can participate and enjoy in, such as the Pacific Unity Festival held annually in Brisbane.

By facilitating improved permanent migration access for Pacific Islanders to Australia, it will not only benefit the island countries by providing an adaptation response to the effects of climate change, it will also benefit Australia overall.

Jillian Ash is an intern at the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific based in Suva, Fiji, where she is providing research assistance for their Pacific Climate Change and Migration Project. More information on the project can be viewed here [pdf] or on the project’s Facebook page. Jillian is also a PhD Candidate in Social Planning and Development at the University of Queensland.