This year’s Australasian AID Conference is a welcome opportunity for aid actors to gather in person after the years of COVID-19 disruption, and reflect on how the world has changed since we last met face to face. There has been an increase in the number of violent conflicts, climate-induced disasters, and an unprecedented global pandemic. Indeed, the effects of climate change in the Asian and Pacific region are increasingly manifest – we’ve recently seen extensive flooding in Pakistan, for example, and several severe tropical cyclones in the Pacific. The challenges of restrictive regimes and displacement continue to loom large, in Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Myanmar for example.

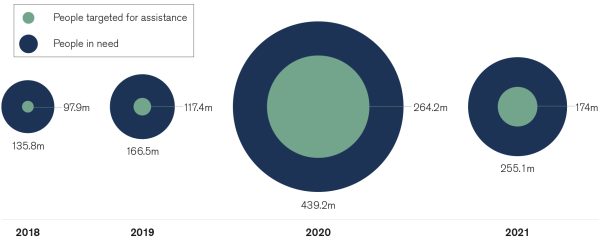

All of these difficulties have led to record numbers of people requiring humanitarian assistance and protection, with a peak of 439.2 million people in need during 2020, in part due to COVID-19. The State of the Humanitarian System (SOHS) report, which the Active Learning Network for Accountability and Performance in Humanitarian Action (ALNAP) publishes every 3-4 years, provides an opportunity to take stock of how effectively the international humanitarian system has tackled these increasing threats, and where more progress is required to meet future challenges.

Figure 1: Number of people in need, 2018–21

Source: UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Global Humanitarian Overview, 2018–2021.

Source: UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Global Humanitarian Overview, 2018–2021.

Notes: These figures include all UN-coordinated appeals covered under the Global Humanitarian Overview, including refugee response plans and flash appeals as well as humanitarian response plans.

In the face of such elevated levels of need, humanitarian actors have worked hard to access and support people affected by crisis. Agencies found ways to pivot during the COVID-19 pandemic, adapting programs and ways of working to tackle health needs and overcome restrictions on movement. Organisations embraced the use of cash as a modality, providing more choice to aid recipients than in-kind goods; 20% of assistance was delivered through cash in 2020. And the system made some shifts away from its traditional responsive model to one that was more anticipatory, with positive outcomes for anticipatory action in the Bangladesh floods, for example.

And yet, despite pockets of progress, as a whole the international humanitarian system has not met the targets and commitments it set itself, including Grand Bargain commitments on localisation and the humanitarian-development-peace nexus. As Figure 2 shows, funding gaps have widened in recent years, with appeals in 2020 only 51% funded – an all-time low. These funding gaps, combined with growing threats including climate change and displacement, require humanitarians to make stronger and more effective linkages with other actors. But progress in this area has been slow, frustratingly so for many people.

Figure 2: Requirements and funding, UN-coordinated appeals, 2012–21

Source: Development Initiatives based on UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Financial Tracking Service (FTS), Syria 3RP (Regional Refugee & Resilience Plan) dashboards and the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) data.

Source: Development Initiatives based on UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Financial Tracking Service (FTS), Syria 3RP (Regional Refugee & Resilience Plan) dashboards and the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) data.

Notes: These figures include all UN-coordinated appeals covered under the Global Humanitarian Overview, including refugee response plans and flash appeals as well as humanitarian response plans. Data from 2012 onwards includes all regional response plans tracked by UNHCR’s refugee funding tracker and all response plans tracked by FTS, including humanitarian response plans, flash appeals and other plans outside of OCHA’s Global Humanitarian Overview. Data is in current prices and was last updated on 22 June 2022.

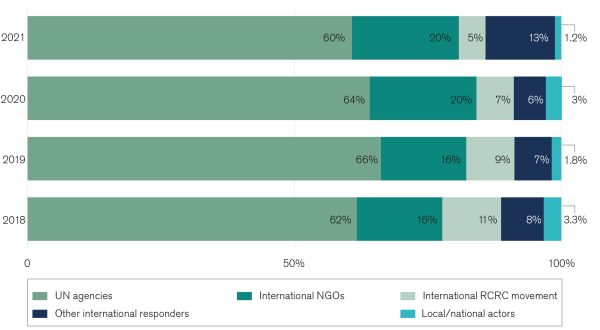

Shifting to a more locally led humanitarian system is not only about money, it is also about changes in power, decision-making and bureaucracy. But the figures do tell an important part of the story. As Figure 3 shows, only 1.2% of all international humanitarian assistance (IHA) went to local actors in 2021, which represents a drop from 3% in 2020 during COVID-19. Despite the key role national and local actors played in the pandemic – for example, local private sector actors and volunteers responding to Cyclone Harold in Vanuatu – the shift in profile and funding we saw in that period has not been sustained. Indeed, the share of all IHA – both direct and indirect funding – sent to local/national NGOs (L/NNGOs) in 2021 was only 1.5%.

Figure 3: Percentage of direct funding to national and local actors compared with other organisation types, 2018–21

Source: Development Initiatives based on UN OCHA FTS data.

Source: Development Initiatives based on UN OCHA FTS data.

Notes: Southern international NGOs, which receive funding to operate within the country where they are headquartered, are included as national actors. Red Cross Red Crescent national societies that received international humanitarian assistance to respond to domestic crises are included in local and national actors. Similarly, international funding to national governments is only considered as funding to national actors when contributing to the domestic crisis response. Funding is only shown for flows that reported with information on the recipient organisation. Data is in constant 2020 prices.

There were some efforts to drive localisation in this period. In a demonstration of their role in shaping change beyond finance provision, some donors – including the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade – have taken a more muscular approach to strengthening the existing capacity of local organisations. However, the aid practitioners we surveyed for the 2022 SOHS described limited progress, in both the system’s support to L/NNGO leadership capacity and power-sharing in decision-making forums. Only 36% and 27% of respondents rated these as either ‘good’ or ‘excellent’, respectively.

The need to build effective links between humanitarian action and development is made vitally important by the protracted crises that comprise the majority of humanitarian need. The number of displaced people around the world continues to grow, with a high of 89.3 million people by the end of 2021 – before the additional impact of the war in Ukraine. Key areas of focus for the humanitarian-development-peace nexus include disaster risk reduction and resilience in the face of climate change, and more durable solutions for refugees. But again, progress has been slow.

Many practitioners are not sure what the triple humanitarian-development-peace nexus means in practice; they do not yet know how to work together and how to ensure accountability for collective goals. As these systems struggle to find effective areas for convergence, crisis-affected people in protracted contexts are finding the aid they receive less relevant to their longer term needs. Indeed, in our 2022 SOHS survey with crisis-affected populations, we saw the percentage of people satisfied with the relevance of the aid they received to their priority needs drop from 39% in 2018 to only 34% in 2021.

Fora like the Australasian AID Conference this week provide an opportunity for humanitarian and development actors – both local and international – to discuss common goals and challenges. In the face of growing global threat, it will be important to sustain the linkages made this week and to turn discussion into action.

The 2022 State of the Humanitarian System report was presented and its key themes discussed at the Australasian AID Conference on 28 November 2022.

Read the 2022 State of the Humanitarian System report.