Possibly the biggest success story in development over the past 20 years has been the global reduction in child deaths. From 12.4 million deaths of children under 5 in 1990, the United Nations estimates that, in 2010, 7.6 million died. This almost 40% reduction is a remarkable public health achievement.

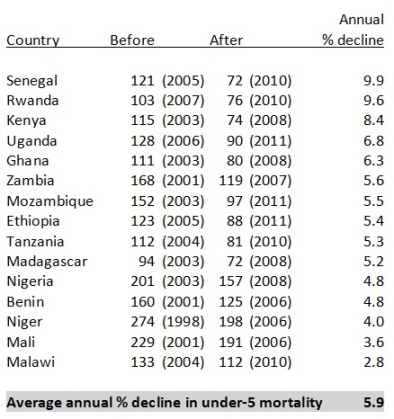

Focusing on sub-Saharan Africa, recent analysis by the World Bank suggests that child mortality is not just in decline but that the decline has greatly accelerated. Using the two most recent Demographic and Health Surveys from 20 African countries, they show huge and rapid declines over the past few years. Senegal, Rwanda and Kenya achieved an annual decrease in child mortality of greater than 8% – the fastest rates of decline seen around the world over the past 30 years. The analysis has received a great deal of press including in the Economist.

Focusing on Kenya, the World Bank was able to attribute 39% of the decline in child mortality and 58% of the decline in mortality of children under 1 to increased ownership of insecticide-treated bednets used to prevent malaria. Malaria – transmitted by mosquitoes – kills up to 1.2 million people in each year around the world.

Focusing on Kenya, the World Bank was able to attribute 39% of the decline in child mortality and 58% of the decline in mortality of children under 1 to increased ownership of insecticide-treated bednets used to prevent malaria. Malaria – transmitted by mosquitoes – kills up to 1.2 million people in each year around the world.

Though this work focused on Africa, reductions in malaria incidence has been seen in the Pacific as well. The last few years of investment in malaria control in Melanesia has seen the number of cases of malaria per 1000 population in Vanuatu decreased from 74 in 2003 to only 14 in 2008. At the same time, the number of cases of malaria in the Solomon Islands decreased by 50,000 contributing to – as in Africa – a reduction in child mortality of 40% since 1990.

This progress has resulted from distribution of long lasting insecticide treated bednets, improved diagnosis and treatment, and indoor residual spraying to reduce mosquito breeding. For example, AusAID has committed $22m to Vanuatu’s malaria control program from 2010-2014 – with a goal of achieving 100 per cent bed net coverage.

Despite these achievements, there has been some criticism of the emphasis on malaria programming overshadowing other efforts in the health sector. In the Solomon Islands specifically, there are a number of organisations engaged in malaria control including the Japanese government, AusAID, SPC, the Global Fund, Rotary International, and the Ministry of Health. Until recently, despite good words about working together, these organisations often duplicated activities and stories of communities playing one donor off another were common. Another risk is that the laser focus on malaria control has drawn attention and resources away from other more general health work. The best health workers were pulled to malaria efforts and boats that took malaria control products to remote islands departed half-empty while other medicines languished due to lack of fuel for transport.

Collaborative efforts over the past year have improved this to some degree and the Sector Wide Approach sees the various development partners sit together periodically to share plans.

The success of malaria control globally highlights the rapid impact of innovation in tools for prevention, diagnostics and treatment. Long-lasting insecticide treated bed nets – to which the World Bank study attributes much of the recent progress – have been recently improved through innovation to last longer and be more effective. Similarly, rapid malaria tests have been developed and more effective artemisinin-based drugs have come onto the market likely contributing to the reductions in transmission.

As AusAID ponders how to increase spending in health research as agreed in the response to the Independent Review, it would make sense to apply the lessons of malaria innovation to tuberculosis. As TB continues to spread throughout Southeast Asia and the Pacific, the tools we have to diagnose and treat TB cannot keep up with the realities of the disease. No new drugs for TB have been introduced in the last 50 years, paediatric formulations don’t exist and diagnostics rely on laboratory capability. With the spectre of drug-resistant TB hovering in Papua New Guinea and Southeast Asia, investments in the TB response – based on the model of success seen in malaria – are well past due.

Joel Negin is a Senior Lecturer in International Public Health at the University of Sydney and a Research Fellow for the Menzies Centre for Health Policy.